Five-Year Evaluation of the Management Accountability Framework

Archived information

Archived information is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject à to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Final Report

Executive Summary

Performance management frameworks are integral to the success of organizations within the public and private sectors. This is especially true for complex organizations such as the Federal Government of Canada.

In November 2008, the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) commissioned PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP and Interis Consulting Inc. to conduct a five-year evaluation of the Management Accountability Framework (MAF), TBS’ performance management framework. As part of this evaluation, we considered how TBS should continue its evolution of the MAF.

Our evaluation approach involved interviews, consultations, literature review, international comparison, a costing survey and cost analysis. We have been greatly assisted by feedback provided by various advisory groups, a DM Steering Committee and discussions with the MAF Directorate within TBS. We note that there were some limitations with respect to the evidence – primarily around the lack of robust costing data as departments and agencies are not tracking costs related to the MAF assessment and empirical evidence with respect the improvement of management practices due to the evolving nature of MAF.

Our evaluation compared MAF against three comparable frameworks in the following jurisdictions: the United Kingdom, the European Union and the United States. The frameworks in place in these jurisdictions are similar in intent (performance improvement) and methodology (regular diagnosis of organizational capability) to the MAF. Key elements of these frameworks that may be leveraged to further enhance the usefulness and sustainability of MAF are as follows.

-

United Kingdom (Capability Review)

- This framework includes additional information gathering techniques such as interviews and workshops, as a means to gather evidence to support the lines of evidence.

- The framework involves increased engagement between the central organization and departments, at the senior levels.

-

European Union (Capability Assessment Framework)

- The framework includes a tailored/flexible assessment approach for each organization or category of organization being assessed.

-

United States (President’s Management Agenda)

- This approach includes an assessment of an organization’s progress towards improvement plans, in addition to the current state assessment.

- An assembly of a deputy head oversight committee is in place to provide input and support to the development of assessment criteria and horizontal issues

A summary of our findings from the multiple lines of evidence is as follows:

- Through formalizing expectations of management, MAF has led to increased focus on management practices, i.e., management matters. MAF is becoming a catalyst for integrating best practices into departments and agencies.

- There continues to be a place for ongoing dialogue between TBS and deputy heads during the MAF process.

- TBS has in place a structured and rigorous process for reviewing the MAF assessment results.

- There has been increasing stability of the MAF indicators in recent rounds

- The current approach of assessing each AoM annually for large departments and agencies does not consider the unique risks and priorities of organizations.

- While the reporting burden associated with MAF has been reduced, there are further opportunities to reduce the impact of the MAF assessment on departments and agencies.

- The subjectivity of the MAF assessments is a result of a significant number of qualitative indicators built into the assessment approach.

- Many of the lines of evidence from Round VI are process-based, which do not measure effectiveness of the outcomes resulting from the process.

- Our consultation indicated that most departments and agencies wee unsure of the cost effectiveness of MAF.

- TBS is the appropriate entity to measure managerial performance with in the Federal Government.

Based on our analysis of the evidence arising from the multiple lines of enquiry, we have concluded that MAF is successful and relevant. MAF is meeting its objectives and it should continue to be maintained and supported. MAF provides a comprehensive view to both deputy heads and TBS on the state of managerial performance within a department or agency. In support of prioritization and focus on management practices across the Federal government, MAF is a valuable tool.

Due to the limitations of the costing data, as noted above, we are unable to conclude on the cost effectiveness of MAF. Going forward, TBS may want to consider providing guidance to departments and agencies to allow the costs of the MAF process to be tracked.

Based on our analysis of the inputs and comparison to comparable jurisdictions, our recommendations for the continued evolution of MAF as a performance enabler are as follows.

- Implement a risk/priority based approach to the MAF assessment process; possible options include:

- Assessment based on the risks/priorities unique to each organization;

- Clustering of the MAF indicators subject to assessment into categories: mandatory, optional, and cyclical;

- Assessment based on the results of previous rounds; and

- Assessment based on department/agency size.

- Develop guiding principles (“golden rules”) for assessing managerial performance and incorporate into the existing MAF assessment methodology, including:

- Maintain an appropriate balance between quantitative and qualitative indicators within each Area of Management (AoM);

- Develop outcome-based indicators of managerial performance;

- Leverage information available through existing oversight activities;

- Maintain the stability of indicators, which is critical to the assessment of progress over time;

- Ensure clarity and transparency of indicators, measurement criteria and guidance documentation;

- Engage functional communities in open dialogue in the ongoing development of AoM methodology and assessment measures;

- Include assessment and identification of both policy compliance and result-based managerial performance; and

- Seek ways to recognize and provide incentives to encourage innovation.

- Introduce a governance body with senior representatives from departments and agencies to guide MAF. This deputy head or departmental senior executive committee could be used to advise on changes to the MAF process and the MAF system-wide results to guide government management priorities.

- Develop a stakeholder communication/engagement strategy and plan, including early engagement when changes are made to the MAF assessment process. TBS could leverage existing communities and forums across the Federal government to ensure timely communication of changes, which will allow stakeholders sufficient time to respond and accept any changes.

- Assign formal responsibilities within TBS to oversee the MAF assessment methodology and framework and management of horizontal issues. This could be achieved by expanding the role of the MAF Directorate within TBS to provide horizontal oversight and integration across AoMs for both methodology and results.

Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Putting MAF in Context

- 3 MAF Assessment

- 4 Recommendations

- Annex A List of Interviewees and Consultation Participants

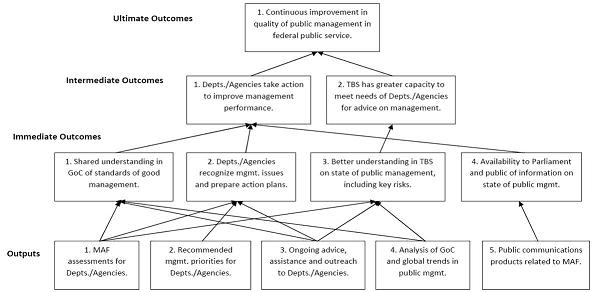

- Annex B MAF Logic Model

- Annex C MAF Alignment with government Priorities

- Annex D International Comparisons

- Annex E Evaluation Questions

- Annex F MAF History

- Annex G Bibliography

1 Introduction

1.1 Overview

In 2003, the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) introduced the Management Accountability Framework (MAF) with the intent of strengthening deputy heads/departmental accountability for management. As a performance management framework, the purpose of MAF1 is to:

- Clarify management expectations for deputy heads to support them in managing their own organizations;

- Develop a comprehensive and integrated perspective on management issues and challenges and to guide TBS engagement with organizations; and

- Determine enterprise-wide trends and systemic issues in order to set priorities and focus efforts to address them.

To emphasize the importance of sound managerial skills for deputy heads, the MAF assessment results form an input into the Privy Council Office (PCO) process for assessing deputy head performance.

The MAF assessment process is managed by the MAF Directorate in the Priorities and Planning Sector within TBS. The MAF is an annual assessment and since 2003, six MAF assessments have been conducted.

1.2 MAF Evaluation

In November 2008, TBS commissioned a five-year evaluation of the MAF. The objectives of this evaluation were to:

- Evaluate how TBS is assessing public sector management practices and performance within and across the Federal government (i.e., is MAF relevant, successful and cost-effective?);

- Compare MAF as a tool for assessing public sector management practices and performance across jurisdictions; and

- Identify and recommend areas for improvement to MAF as an assessment tool and its supporting reporting requirements, tools and methodologies.

A combined team from PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (PwC) and Interis Consulting Inc. (Interis) were contracted to complete the evaluation. The evaluation questions were developed by TBS with input from the deputy head community; with the overall evaluation approach agreed upon by TBS.

Evaluation Methodology and Approach

The evaluation was initiated with the clear objective of performing an assessment of MAF and developing recommendations for improvement. The Statement of Work (SOW) developed by TBS identified 23 evaluation questions. We based our evaluation framework on those questions, developing indicators and evaluation methods to address each question. As well, to support an integrated analysis, we grouped the evaluation questions into four strategic questions (Annex E identifies the 23 evaluation questions and their grouping under the four strategic questions).

In addressing the evaluation questions, multiple sources of evidence were used. This included document and literature reviews, interviews, consultations and roundtables with stakeholder group representatives, international comparison against comparative jurisdictions and a costing analysis.

A brief summary of our data gathering approach is as follows:

-

Document/Literature Review: Documents were provided by TBS personnel and additional literature was researched by the evaluation team. The literature reviewed, as

listed in Annex G, was used as follows:

- As a basis for analyzing whether MAF is achieving its objectives and the assessment of the MAF process and associated tools; feedback on past assessment rounds and process documentation was used to corroborate information gathered from interviews and consultations;

- To contextualize MAF as a performance management framework, literature review was used to identify established theories/approaches in the area of performance management;

- In order to assess MAF’s performance relative to comparable models in place in other jurisdictions, the literature review identified key elements of each model, provided international perspectives and feedback on MAF and the other models to compare successes and challenges with the various models. This information corroborated feedback obtained and analysis performed relative to what elements of these other models may be considered within MAF. The literature review was used to assess each comparable framework to MAF within three broad categories: nature and objective of the framework, the assessment methodology and the outcome of the assessment.

-

Interviews with Key Stakeholders2: Interviews and consultations were conducted as follows:

- Departmental and agency interviews were conducted with 27 deputy heads and four separate group consultations were held; two with the departmental MAF representative (ADM-level) community, one with the MAF Network and one with the Small Agencies Administrators Network (SAAN)3.

- Interviews and consultations were also held with central agency stakeholder groups including: Secretary of Treasury Board, Program Sector Assistant Secretaries, Policy Sector Assistant Secretaries, Area of Management (AoM) leads and the Privy Council Office.

- International Comparison: As part of this evaluation, we were asked to compare MAF against specific international comparator jurisdictions. Our comparison exercise included the United Kingdom, United States and European Union. An overview of the results is provided in Section 2.0 of this report and details are provided in Annex D. We also consulted with a team of international representatives within our firms who provided advice and feedback to the evaluation team on the approach and results of the international comparison.

- Costing Survey and Analysis: As part of this evaluation we were asked to conduct a quantitative assessment of the costs of MAF. To do this, we asked 21 departments and agencies and TBS to provide an estimate of the approximate level of effort for each individual involved in the MAF assessment for Round VI.

-

Walk-through of the MAF Assessment Tool and Process: In conjunction with the information gathered from the individual interviews and consultations, detailed documentation

review of the MAF assessment process was conducted in order to analyze the effectiveness and efficiency of the process and the associated communication approaches and support

mechanisms.

The MAF Portal and the MAF Assessment System were assessed as tools to effectively and efficiently administer the assessment process. This analysis was achieved through a walk-through and in-depth interview on the assessment process and the supporting functionality of the databases. The information gathered was corroborated by literature review and the results of interviews and stakeholder consultations.

-

Analysis of the AoMs and Associated Assessment Methodology: Detailed analysis was performed for each of the 21 AoMs, including:

- Trend of results by organization over assessment rounds;

- Comparison of weighting approach to arrive at the overall assessment rating per AoM (i.e. decision-rule based, weighted average, average, points-based);

- Comparison and analysis of the rating criteria for each AoM – specifically focusing on the trends between Round V and VI for the definition of a “Strong” rating and the precision of definition over time;

- Year over year comparison between Round V and VI of the number and nature of changes to the lines of evidence per AoM; and

- Categorization of AoMs according to level of subjectivity of assessment criteria, process vs. outcome-based indicators and level of definition of maturity model within the assessment criteria.

Evidence from each of these sources was analyzed and synthesized to develop the findings, conclusions and recommendations that are included in this report. Figure 1 below depicts, at a high level, the evaluation framework we used, including the linkages between the four strategic questions and the three main evaluation issues expected to be covered by the TB Evaluation Policy.

During the course of the planning, conduct and reporting phases of the evaluation, oversight and guidance was obtained from the following sources:

- Deputy Minister Steering Committee: A deputy minister steering committee was established to oversee the evaluation and to provide feedback and advice to the evaluation team at key points. The members of the deputy minister steering committee are presented in Annex A.

- Departmental Evaluation Committee: Throughout the course of the evaluation, members of TBS’ Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau and the Evaluation Committee provided oversight and input into the evaluation approach and associated deliverables.

- International Advisory Committee: A selection of international public sector, senior experts was assembled to provide guidance, oversight and advice on key milestones and deliverables during the evaluation process.

Limitations of the Evaluation. The following are the main constraints we faced in completing the evaluation as planned:

- Accuracy/Validity of the MAF Assessment Process/Tool: The evaluation assessed the robustness, relevancy, validity and accuracy of the MAF assessment tool focusing on the methodology, including the lines of evidence, the assessment criteria and rating approach. While the evaluation found that the MAF assessment process is robust and the results generally reflect the realities of organizations, it was not able to conclusively determine the validity or accuracy of the tool as MAF necessarily relies upon both qualitative and quantitative indicators. Once the recommendations from this evaluation have been implemented and the next phase of MAF maturity has been established, it may be appropriate to consider a more in-depth analysis of the accuracy of the individual AoM results.

- Cost Effectiveness of MAF: As departments and agencies are not tracking costs related to the MAF assessment process, we were unable to complete a comprehensive costing analysis within departments and agencies to support our assessment of cost-effectiveness. The results of the costing analysis did identify a range of approximate dollars spent on MAF during Round VI. Consideration should be given to additional work to better identify the costs associated with MAF to allow a baseline to be established to compare trends, including, as an example, the reduction in reporting burden over time.

-

Quantitative Evidence to Demonstrate Impact on Management Practices: Given the fact that the TBS scoring approach and indicators are evolving, we were unable to identify

quantitative evidence (based on MAF scores) whether management practices have improved as a result of the introduction of MAF – for this perspective, we relied on interviews and workshops

to gather opinions from departments and agencies and TBS.

Related to the above two points, without reliable data on costs or an ability to measure improvement on MAF scores, we were unable to draw any correlation between departmental investment in MAF and MAF performance.

-

International Comparison: As outlined in section 2.2 on international comparisons, although we were asked to review approaches in Australia and New Zealand, we determined

they were not comparable for our purposes because they either had a different focus or were not implemented public-sector wide. Instead, we compared MAF to approaches used in the United

Kingdom, the European Union and the United States.

For the comparator models included in our international research, there was limited data available regarding the costs of the programs. As well, we were unable to identify any conclusive data relating management performance to achievement of organization goals.

- Validation of the MAF Logic Model: The logic model for MAF was developed after this study’s methodology was designed and initiated. Accordingly, it was not possible to identify direct linkages between MAF and improvements to departmental management performance. In the absence of a logic model, the evaluation team used the objectives of MAF as communicated in the Request for Proposal for this evaluation. While including the draft logic model in this report was essential in the context of an evaluation, it should be validated with key stakeholders.

MAF is an information-gathering tool used by TBS to assess departmental management performance; which in turn, is critical to ensuring that programs and services are delivered to the highest standards in the most cost-efficient fashion.

Given the qualitative and subjective nature of MAF, as a tool to assess management performance, the foregoing limitations are reasonable. The evaluation team was able to address the evaluation questions by engaging relevant stakeholders and corroborating information gathered through multiple lines of evidence. As a result, it is our view that the evaluation standards, as defined in TB Evaluation Policy (2001), have been met.

1.3 Purpose of Report

The purpose of this report is to provide:

- An assessment of MAF performance to date;

- An analysis of key issues including: governance; methodology of assessments; reliability and accuracy of assessments; reporting requirements; systems; process; treatment of entities and alignment to the Federal government’s planning cycle and other initiatives; the analysis encompasses international comparisons to other managerial performance models; and

- Recommendations for proposed changes to MAF, with the intention to improve the functionality and sustainability of MAF, as a result of the key issues identified.

1.4 Conclusions

As we describe in detail in section 3 of the report, we have concluded that MAF is successful and is meeting its current objectives. MAF has clarified management expectations for deputy heads, has guided TBS engagement with departments and agencies, and provided both an enterprise-wide view of management practices to departments and a view to government-wide trends and management issues to TBS.

Further, we have concluded that MAF is a valuable and relevant management tool that should continue to be maintained and supported. In stating this we note that, driven by the need to meet increasing expectations for clear demonstration of accountability within the public sector, MAF has evolved significantly since its inception in 2003, from a relatively informal approach to a much more rigorous assessment. Based on the results of our international comparison, it is reasonable to conclude that had MAF not existed, something similar would have been needed to meet these increased accountability requirements.

While we were unable to conclude on the cost effectiveness of MAF, due to limitations of the costing information available, or on the accuracy/validity of the assessment results, we were able to conclude that the MAF assessment process is robust and the results generally reflect the realities of organizations.

We have identified areas improvements that can be made to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of the MAF process and enhance the overall validity of the assessment results. Going forward, TBS may consider developing a costing approach that once implemented, would establish a baseline to compare cost in future years. Further, validation of the MAF logic model with key stakeholders will be essential for its use as a basis for future performance measurement.

Finally, to ensure that MAF continues to meet its objectives and continues to support efforts towards management excellence, we have concluded that MAF should continue its evolution as a performance enabler for deputy heads. The recommendations outlined in Section 4.0 will support this transition.

2 Putting MAF in Context

2.1 Importance of Performance Management Frameworks

To achieve organizational goals, organizations must motivate individuals and groups towards a common goal; performance management is a means used to get there. Performance management is defined as a cycle of managerial activities that includes planning, measuring results and using measurement to reflect on the accomplishment of objectives.4 This cycle can be applied at the various levels: individual, team/business unit or organizational level. Fundamentally, this involves integrating goal setting, measurement control, evaluation and feedback in a single ongoing process aimed at fostering continuous improvement in the creation of value. A performance management framework usually refers to a specific process to accomplish the performance management cycle. These frameworks usually include:

- Planning – identifying goals and objectives;

- Measuring – assessing extent to which goals and objectives have been achieved;

- Reporting – monitoring and reporting of key performance results; and

- Decision Making – using the findings to drive improvement/manage opportunities in the organization, department, program, policies or project.

Effectively managing business performance in today’s complex, ever changing, competitive environment is critical to the success of any organization. In fact, studies5 have shown that organizations that manage performance through measurement generally are far more successful than those that do not. For example, TBS’ implementation of the MAF has resulted in an increased focus on improving managerial performance within departments.

There are a number of benefits that organizations can reap by implementing a performance management framework. Some other benefits that can be accrued to organizations are:

- Alignment of activities to the goals and objectives of the organization.

- Achievement of organizational goals and objectives through appropriate allocation and focus of resources on performance drivers.

- Measurement of the organization’s progress towards outcomes.

These benefits can be realized when an effective performance management system is implemented. An effective performance management system “encourages employee behaviours that drive positive results whereas an ineffective performance management system, at best, utilizes rewards inefficiently and, at worst, adversely affects the outcomes that it is intended to improve.”6

2.2 International Comparison

As part of this evaluation, we conducted an international comparison of the MAF against approaches currently used by other public sector jurisdictions. Specifically, we compared the MAF against management performance frameworks used in the United Kingdom (UK), the European Union (EU) and the United States (US).7

We did review approaches in Australia and New Zealand but determined they were not comparable for our purposes because they either had a different focus or were not implemented public-sector wide. In Australia, the Executive Leadership Capability Framework is a competency framework, not an overall management performance framework. In New Zealand, the Capability Toolkit shares similarities with MAF but the framework is used on a voluntary basis and limited information is available on the impact of its application across the public service.

Internationally, MAF is considered to be one of the more sophisticated management practices systems. For example, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)8 "An exceptional model for widening the framework of performance assessments beyond managerial results to include leadership, people management and organisational environment is provided by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) Management Accountability Framework (MAF)."

An overview of each framework is provided below, with more details provided in Annex D to this report.

|

Attribute |

MAF (Canada) |

Capability Review (UK) |

Common Assessment Framework (EU) |

President’s Management Agenda (US) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Purpose |

Clarify management expectations and to foster improvements in management |

Assess organizational capability to meet the government’s delivery objectives |

Improve public sector quality management |

Improve agency performance in five specific areas |

|

Methodology |

Annual review by central agency (exceptions for small and micro-agencies) |

External review with six, 12 and 18 month stock takes; second round review after two years |

Internal reviews on an optional basis in line with the results of the self-assessment |

Quarterly self-assessments |

|

Assessors |

TBS personnel review of documentation and questionnaires |

Three assessors from outside central government and two director generals from other government departments review documentation and conduct interviews; input and analysis provided by the Cabinet Office |

Self-assessment; project teams internal to the organization |

Office of Management and Budget (OMB) reviews internal, progress indicators and Green Plans |

|

Judgment vs. Evidence-based |

Judgment and evidence-based criteria |

Judgment and evidence-based criteria |

Judgment and evidence-based |

Evidence-based |

|

Remuneration |

Linkage to performance pay of deputy heads through the Committee of Senior Officials |

Linkages to salary decisions of Permanent Secretaries |

Depends on how the framework is applied |

Linkages to both budget allocations and Chief Operating Officer evaluations |

|

Treatment of Entities |

One size (exception: small and micro agencies assessed using different standard on a three-year basis) |

Consistent approach for all organizations assessed |

Adaptable by organizations |

Consistent approach for all organizations assessed |

|

Publication |

Yes, on TBS website and optionally on departments’ websites; often includes a management response |

Yes, on agency’s websites and press release |

Voluntary submission of scores into CAF database |

Yes, on department’s websites |

United Kingdom’s Capability Review

The UK’s Capability Review (CR) program was launched by the Cabinet Secretary in 2005. The CR was the first organizational capability assessment framework in the UK to assess systematically the organizational capabilities of individual departments and to publish results that can be compared across departments. Its objective is to improve the capability of the Civil Service to meet the government’s delivery objectives and to be ready for program delivery.

The CR addresses three broad area of management capability: leadership, strategy and delivery. Using a standard list of questions and sub-criteria related to 10 elements within the three broad management areas, a review team completes its analysis using a combination of evidence/surveys provided by the department and conducts interviews and workshops over a short two to three week period.

Using judgment and based on the information gathered during the assessment period, the review team assigns a rating to each element along a five-point scale: strong, well placed, development area, urgent development area or serious concerns. Results of the review are published, which sets out areas for action. The debriefing process is an honest, hard-hitting dialogue between the Cabinet Secretary, the Head of the Home Civil Service and the departments upon which action plans are devised.

For the first round of reviews, all major government departments were reviewed in five tranches between July 2006 and December 2007.9 A three-month challenge and a six-month, 12-month and, as necessary, an 18-month stock take takes place to ensure the department is making progress towards the action plan. Second-round reviews take place after two years of the original first-round review.

The CR is managed and organized by the Cabinet Office. In an effort to bring a level of independence to the review results, the five-person review teams include two private sector external experts, one local government representative, in addition to the two representatives from peer government departments.

The CR has been well received in the UK as departments think that it has added value. The use of a review team external to the department adds a level of independence to the results. A significant amount of judgment is applied when assessing departments within the CR. The application of judgment is critical when assessing organizational capability; however, this also increases the subjectivity within the results of the review. While the reviews rely on judgment, they are based on evidence that can be compared from one department to another and the assessments are reviewed by an independent external moderation panel to ensure consistency. Finally, although the CR was designed to assess departments’ capability to meet current and future delivery expectations, no direct correlation has been made between capability and delivery performance.

European Union’s Common Assessment Framework

In 2000 the Common Assessment Framework (CAF) was launched by the European Public Administration Network (EUPAN) as a self-assessment tool to improve public sector quality management within EU member states. It is based on the premise that excellent results in organizational performance, citizens/customers, people and society are achieved through leadership driving strategy and planning, people, partnerships and resources and processes. It looks at the organization from different angles at the same time, providing a comprehensive and integrated approach to organization performance analysis.10

The CAF is based on the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) and the model of the German University of Administrative Sciences in Speyer. It is composed of nine criteria, categorized into two broad segments - Enablers and Results – that define the cause and effect relationship between organizational capabilities. Each criterion is subdivided into sub-criteria, for which examples demonstrate that specific managerial practices are in place.

The CAF is not imposed on organizations within the EU;11 it is a voluntary tool provided to agencies as a means to improve organizational effectiveness. As a result, the CAF is a self-assessment tool completed within the agency being assessed. Typically, an internal review team is assembled within the organization who applies judgment of organizational performance against the indicators. The CAF was not designed to be a one-size-fits-all model. Flexibility has been built into the approach to allow for tailoring for the needs of the organization. For example, a number of specialized CAF models exist for different sectors (e.g., education, local government, police services and border guards). Finally, the CAF does not prescribe what specific organizational practices need to be in place; only the broad practices that needs to be in place.

The key advantage of the CAF is the flexibility that is built into the framework; allowing each organization to respect the basic structure of the framework while applying only relevant examples in the self-assessment process. This ensures the relevance of the results to the organization. However, the voluntary and self-assessment nature of the assessment tool limits the rigor, independence and comparability of the results over time and across organizations.

United States’ President’s Management Agenda

The President’s Management Agenda (PMA), launched by the Bush Administration in 2001, focuses on improving organizational effectiveness in five key areas of management across the whole of the US government. The program was established to improve the management and performance of the federal government and deliver results that matter to the American people. The PMA is not a comprehensive assessment framework; rather, it defines five specific government-wide initiatives thought to be of importance at the time. These include: i) Strategic Management of Human Capital, ii) Competitive Sourcing, iii) Improved Financial Performance, iv) Expanded Electronic Government and v) Budget and Performance Integration.

Each initiative, for all 26 major federal departments and agencies, is scored quarterly using a red, yellow and green system. The PMA uses a “double scoring” approach whereby the red, yellow, green score is applied for the current status as well as for progress. Progress in this case is defined as the execution of improvement plans based on the current assessment status. The PMA uses a self-assessment approach based on the standards that have been defined for each initiative. The head of each agency (Chief Operating Officer) is responsible for conducting his/her own agency’s assessment on a quarterly basis.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB – in the Executive Office of the President) is responsible for the PMA; however, the President’s Management Council, made up of Chief Operating Officers for all 26 agencies, meet regularly to review progress against the PMA for all agencies.

While the PMA consists of a standard process for each organization, it is limited in its focus to those five key government-wide management priorities. Consistent with the CAF, the self-assessment approach, which is practical given the quarterly assessment cycle, can limit the rigor and independence in the assessment results; however, this is balanced by the oversight of the President’s Management Council, which would be the equivalent of a deputy head oversight committee.

Further details of each comparative jurisdiction have been provided in Annex D to this report.

Applicability to MAF

Our review of the frameworks in place in other jurisdictions indicates that the tools being used are similar in intent (performance improvement) and methodology (regular diagnosis of organizational capability) to the MAF. Further, all jurisdictions appear to face similar challenges including demonstrating the link between the assessment and ultimate performance improvement, the ability to define clear measures, and finding ways of improving the efficiency of the approaches.

There are opportunities for MAF to leverage elements of these frameworks to further enhance the usefulness and sustainability of the tool. A summary of the key considerations for MAF from the international comparison exercise, which will be further examined in Section 3.0 below, is as follows.

- Consider conducting interviews and consultations, as a means to gather evidence to support the lines of evidence.

- Incorporate flexibility into the MAF assessment process by facilitating a tailored assessment approach for each organization or category of organization being assessed.

- Increase the level of engagement between TBS and departments, at the senior levels.

- Assemble or leverage an existing deputy head committee to provide input and support to the development of assessment criteria and horizontal issues identified through MAF.

- Consider assessment of an organization’s progress towards improvement plans, in addition to the current state assessment.

3 MAF Assessment

Based on a series of 23 questions identified by a group of deputy heads, we developed four key strategic questions to support our review of MAF as a management performance assessment tool, the associated methodology and administrative practices and the benefits of MAF, relative to costs. The four strategic questions are as follows:

- Is MAF meeting its objectives?

- Are MAF assessments robust?

- Is MAF cost effective?

- Is MAF governance effective?

A brief overview of the MAF process is outlined below. In the sections that follow, each of the four questions are individually addressed, including a conclusion for each strategic question.

3.1 MAF Model, Process and Cycle

The MAF is structured around 10 broad areas of management or elements: governance and strategic direction; values and ethics; people; policy and programs; citizen-focused service; risk management; stewardship; accountability; results and performance learning, innovation and change management. Figure 2 below displays the 10 MAF elements.

Figure 2 - Display full size graphic

Organizations are assessed in 21 Areas of Management (AoM); each of which have lines of evidence with associated rating criteria and definitions to facilitate an overall rating by AoM. The four-point assessment scale measures each AoM as either strong, acceptable, opportunity for improvement or attention required. The MAF Directorate, within TBS, has recently developed a logic model for MAF to clearly articulate the outcomes. The logic model is presented in Annex B to this report. It is important to note that MAF is not the sole determinant of a well-managed public service. Apart from its broad oversight role as the Management Board and Budget office, TBS oversees Expenditure Management System (EMS) renewal (whereby TBS advises Cabinet and the Department of Finance on potential reallocations based on strategic reviews to ensure alignment of spending to government priorities) and the Management Resources and Results Structure Policy (which provides a detailed whole-of-government understanding of the ongoing program spending base). The alignment of MAF to government priorities is presented in Annex C.

The MAF assessment process is performed annually by TBS based on evidence submitted from departments and agencies to support the defined quantitative and qualitative indicators within the framework. Assessments are completed by TBS representatives, including a quality assurance process to ensure results are robust, defensible, complete and accurate.

For each assessment round, all 21 AoMs are assessed for every department and agency, with the following exceptions:

- Small agencies (defined as an organization with 50 – 500 employees and an annual budget of less than $300 million) are only subject to a full MAF assessment every three years, completed on a cyclical basis. In Round VI, eight small agencies were assessed.

- Micro agencies (defined as an organization with less than 50 employees and an annual budget of less than $10 million) are subject to a questionnaire, which informs an interview with TBS senior representatives with the submission of supporting documents, as applicable. In Round VI, three micro agencies were assessed.

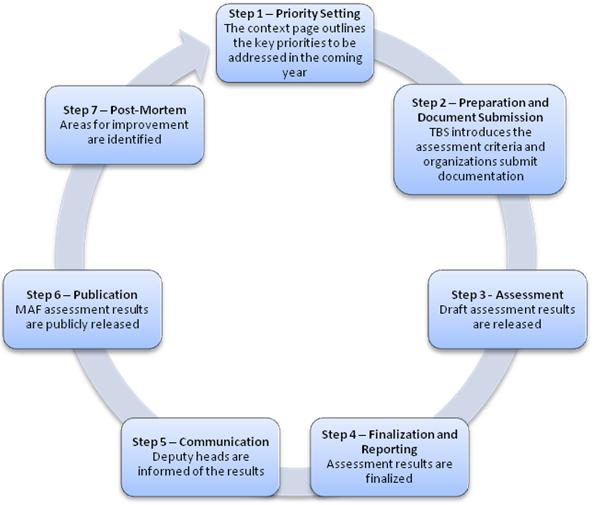

The main steps to the MAF assessment process are detailed below:

Step 1 – Priority Setting: The MAF assessment process begins with the previous round’s context page provided by TBS to the deputy head, which outlines the key priorities to be addressed in the coming year. During the year, action plans and efforts are made by the departments and agencies to address the identified deficiencies and improve managerial performance within the organization.

Step 2 – Preparation and Document Submission: In advance of the assessment round, TBS conducts awareness and training sessions to introduce changes in the assessment criteria. Once the assessment round commences and based on the documented assessment and rating criteria developed for each AoM and line of evidence, departments and agencies submit documentation to enable an assessment against the measures.

Step 3 - Assessment: The process to arrive at a preliminary assessment includes detailed analysis, reviews and approvals within the policy and program sectors of TBS. This includes vertical (a review of all AoM results for an individual department or agency) and horizontal reviews (a comparison of AoM results across all departments and agencies assessed), which are performed by senior TBS officials. Once completed, the draft results are presented at a TBS Strategy Forum session whereby the Associate Secretary, the Program Sector Assistant Secretaries and the AoM Leads review and discuss the draft results on a department by department basis. Based on the results of the Strategy Forum, the draft assessment results are released to the individual departments and agencies for feedback.

The MAF Portal

The MAF Portal is the tool used to facilitate the submission of evidence to address the lines of evidence and to ensure timely and effective communication between TBS and departmental MAF representatives. The Portal was piloted at the beginning of MAF Round V to facilitate and improve communications between TBS and departments and agencies. Since then, it has become an essential tool for both TBS and MAF respondents for executing the MAF process. The Portal facilitates the departmental submission of documents to TBS for use as evidence to support MAF assessments and ratings and enables the archiving of all documents sent electronically by departments and agencies.

TBS uses a web-based application called the MAF Assessment System, which is linked to the MAF Portal. This application has been developed and enhanced during the past three MAF assessment rounds and is used to process and archive the TBS assessment activities.

Step 4 – Finalization and Reporting: Based on feedback from the departments and agencies, the assessment results are finalized. In addition, a context page and a streamlined report are drafted to support the assessment results and identify management priorities for the upcoming year. A second TBS Strategy Forum session is conducted to provide guidance on any context pages, streamlined reports or assessment ratings and to finalize the materials and obtain consensus on the final departmental assessments.

Step 5 - Communication: The final reports are approved by the Secretary of the Treasury Board and a letter is sent by the Secretary to each deputy head informing them of the results and identifying priorities to address in the upcoming year. To provide support in the development of action plans, bilateral debriefings are scheduled between the deputy head and the Secretary for selected departments, with the Program Assistant Secretaries addressing the remaining departments. This is complemented by the Committee of Senior Officials (COSO) process, whereby the Clerk (or Deputy Clerk) of the Privy Council provides direct feedback to each deputy head regarding his/her performance, including the MAF results for his/her department. Beyond the deputy head community, to facilitate broader communication to all departmental officials involved in the MAF assessment process, departmental results are posted in the MAF portal.

Step 6 – Publication: To ensure transparency to the public, the MAF assessment results are publicly released on Treasury Board’s website.

Step 7 – Post-Mortem: Once the round concludes, the MAF Directorate launches a post-mortem with Treasury Board Portfolio (TBP) staff, management area leads, and MAF coordinators in various departments and agencies. The purpose of the post-mortems is to assess the process and methodology to identify areas for improvement to be integrated into the subsequent round. Recommendations are made with appropriate consultations of TBP staff and the MAF Directorate and may include improvements to the process and/or timelines, adjustments to management areas, the introduction of new models or methodology, or additional training. TBP’s Management Policy and Oversight Committee and the Secretary of the Treasury Board are responsible for approving any recommendations before implementation into the next round.

Figure 3 summarizes the key milestones within the MAF assessment process.

The MAF Directorate has taken a leading role in supporting MAF’s evolution and addressing concerns of stakeholders. During Round VI, the MAF Directorate facilitated a Leading Management Practices conference for departments and agencies. This forum provided TBS’ guidance on specific AoMs where horizontal results across departments and agencies were weaker, and showcased departments and agencies of various sizes who had successfully implemented best practices within individual AoMs. AoM leads have also take initiative to facilitate dialogue and efforts to address horizontal issues identified as a result of MAF by leveraging existing functional communities, including Information Technology, Internal Audit and Financial Management communities, as examples.

Other initiatives undertaken by the MAF Directorate include the development of MAF methodology and guidance documents, the management and improvement of the MAF Portal, the development of the MAF logic model and the framework for a risk-based assessment approach.

3.2 Is MAF Meeting Its Objectives?

As it has only recently been developed, we were unable to base our evaluation approach on the MAF logic model presented in Appendix B. In evaluating MAF, we identified that it has evolved from an initial “conversation” between deputy heads and TBS to a much more defined, rigorous and documented assessment. Through our interactions with TBS, we confirmed that this evolution was a conscious approach to address the increasing expectations for clear demonstration of accountability within the public sector12. As such, we determined that to be of most use, the evaluation should focus on the current objectives for MAF, as outlined in section 1.1 of this report, rather than the initial goals.

It is our view that MAF is meeting its stated objectives. MAF provides both an enterprise-wide view of management practices to departments and a view to government-wide trends and management issues for TBS. In addition, we think the 10 key elements of the MAF framework provide an effective tool to define “management” and establish the expectations for good management within a department or agency; a view shared generally by key stakeholders, and supported by our review of other models.

In our interviews and consultations, we consistently heard and observed that MAF and the associated assessment process has led to increased focus on management practices and has become the catalyst for best practices. As reflected in the MAF logic model reflected in Annex B to this report, an ultimate outcome of MAF is “continuous improvement in the quality of public management in the Federal public service.” With this goal in mind, there are opportunities for future evolution to ensure ongoing sustainability, usefulness and achievement of the expected long-term outcomes.

MAF has resulted in a number of unintended impacts, both benefits and consequences. The unintended benefits have included:

- Sharing of best practices and encouraging communities of interest;

- International recognition of Canada’s leading edge management practices;

- Increasing transparency of government; and

- The use of MAF results by deputy heads new to the department or agency, to get the initial ‘lay of the land’.

Conversely, the unintended consequences have been:

- Increased reporting burden for departments and agencies and the creation of ‘MAF response’ units;

- Ineffective resource allocation in an effort to improve the MAF scores; and

- Potential for rewarding adherence to process rather than outcomes.

1. Through formalizing expectations of management, MAF has led to increased focus on management practices, i.e., management matters. MAF is becoming a catalyst for integrating best practices into departments and agencies.

Several of the deputy heads interviewed stated that they use the AoMs to set managerial priorities and expectations with the department’s senior management team. For example, MAF has influenced performance agreements with senior management teams, whereby deputy heads include MAF results as a measure of individual performance. This has included creation of such tools as a MAF Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) or other performance agreements between the Deputy Minister and the Assistant Deputy Minister.

TBS has been able to leverage MAF results to clarify management expectations for deputy heads, provide incentives to departments and agencies to focus on management and determine enterprise-wide trends. For example, based on the results of individual organization assessments, TBS has been able to provide direction to departments and agencies for short-term priority setting. We understand that TBS has used MAF results to inform oversight activities and support intelligent risk taking. By using MAF results to target oversight in the highest risk areas, TBS can recommend and support increasing departmental autonomy for a department to innovate and take risks. Examples where MAF results currently inform oversight activities include delegations of authority, budget implementation decisions, Strategic Reviews and Treasury Board submissions.

There are opportunities to use the MAF assessment process to showcase and further provide incentives and recognize innovation across the Federal government. In 2009, a report on the Operational Efficiency Programme in the UK, recommended that, “the Cabinet Office should embed departmental capability and track record in fostering innovation and collaboration in Capability Reviews.”13

MAF has facilitated the identification of government-wide issues and the development of associated action plans. As owners of the individual AoMs, AoM leads within TBS are responsible for addressing these systemic issues that are identified through the MAF results. Enterprise trends and systemic issues identified through the AoM assessments are discussed at the Public Service Management Advisory Committee (PSMAC). PSMAC (formerly the Treasury Board Portfolio Advisory Committee (TBPAC)) serves as the focal point for integrating and ensuring coherent, comprehensive and consistent implementation of the Treasury Board’s integrated, whole of government management agenda. TBS also provides a précis to deputy heads, identifying horizontal management issues. By facilitating sharing of best practices across departments and agencies and existing common interest communities, TBS is supporting efforts to prioritize and address these issues.

2. There continues to be a place for ongoing dialogue between TBS and deputy heads during the MAF process.

“The next generation of MAF: it would interesting to sit down with TBS, where they would identify the things they are going to be looking at. Having that kind of dialogue ahead of time and setting the standard of performance for the year.” (Source: deputy head interview)

As noted above, MAF has evolved from an initial “conversation” between deputy heads and TBS to a much more defined, rigorous and documented assessment. This has allowed TBS to leverage MAF to support its oversight and compliance monitoring role relative to its policy framework.

We think that MAF has matured to the point that more emphasis could be placed on the level of conversation or engagement between TBS senior officials and deputy heads. We heard consistent concerns, across a majority of our deputy head interviews, that the “process” has overtaken the “conversation”. This results, at least in part, from the broad scope and frequency of the MAF assessments, which limits the time and ability of TBS senior managers to engage in meaningful, two-way conversations with all departments. This has led to the perception, among both larger departments, as well as smaller agencies, of TBS as an assessor rather than an enabler. To fully achieve the objectives set out for MAF and provide the expectations of managerial performance, there is an opportunity to more formally engage senior departmental representatives.

For the UK Capability Reviews, engagement at the senior level is seen as a critical part of the review. As outlined in Take-off or Tail-off? An Evaluation of the Capability Reviews Programme, the consultation and interactions between the permanent secretary and the departmental boards are honest, intense, emotional and hard-hitting, and need to occur in order to drive real change within the department.

Many deputy heads indicated that they would welcome priority setting and performance review discussions with senior executives within TBS (the Secretary or Assistant Secretaries). Of the 19 deputy heads that raised the issue of having priority setting discussions with senior TBS officials, 100% agreed that they would welcome such discussions. Regardless of stronger or weaker performance, deputy heads believed strongly that these discussions are important for the departments to address their organization’s current circumstances, communicate their priorities for the year and agree on the performance priorities and expectations.

The existing strategy in the UK for communicating results externally has been much more publicized and visible as compared to MAF, including press releases of results. While this approach has been designed to ensure the impact of the results, we do not think that there is a benefit to this approach for MAF.

3.3 Are MAF Assessments Robust?

“There are hidden costs of NOT doing MAF.” (Source: deputy head interview)

In our view, as a tool for the assessment of departmental managerial performance, the existing assessment approach and methodology for MAF assessments has a solid foundation. We also noted that it is consistent with the basic elements of assessment models in place within other jurisdictions. TBS has identified areas of improvement to support improved efficiency and effectiveness of the tool and took steps to streamline the process for Round VI; however, stakeholders were quick to express concern over making too many changes or streamlining too much to diminish the focus on management.

Over the past six rounds of MAF, departments and agencies have taken strides to embed MAF and strong managerial performance into their organizations, pushing the expectations through to their senior management and management teams. To ensure the continued progression towards this goal and to complement the ongoing “ever-greening” of the assessment tool, enhancements to the assessment methodology and approach should be considered. By incorporating key elements to ensure transparency and defensibility of measures, as well as improvements to the process to increase its efficiency and effectiveness, this will support efforts towards management excellence.

3. TBS has in place a structured and rigorous process for reviewing the MAF assessment results.

As outlined in Section 3.1 of this report, the current assessment approach uses central agency representatives to complete the assessment with a quality assurance process to support the accuracy of the assessment results.

Our discussions with departmental representatives at all levels point to most not being aware of the extent of the quality review process within TBS (detailed in Section 3.1 of this report). While the MAF assessment process begins with an assessment by analysts, it also involves several quality control and approval steps involving more senior staff, and leads to review and approval at the Associate Secretary and Secretary level. A key step in this process is the Strategy Forum, involving Assistant Secretaries from the Program and Policy Sectors, as well as all AoM leads, where the draft results for all departments and agencies across all AoMs are reviewed and assessed. This Strategy Forum is conducted twice; once before the finalization of the draft assessment results and the other prior to the release of the final assessment and context page. This is a key internal governance step in the assessment process to ensure there is a consensus within TBS regarding the MAF assessment results. Ongoing communication with departmental stakeholders will allow organizations to understand and gain confidence from the existing quality assurance processes already in place. This could include consideration of how to communicate results to Parliamentarians.

In the consultation process for this evaluation, a majority of departmental stakeholders raised concerns regarding the TBS analysts involved in the assessments. These concerns relate mainly to the rate of turnover of the analysts from one year to the next, which impacts the level of the analysts’ experience. Consistent with other areas of the Federal government, we have learned that turnover of analysts is part of a larger and ongoing talent management challenge.

4. There has been increasing stability of the MAF indicators in recent rounds.

”One of the complaints that departments have every year is we change the rules of the game.” (Source: Senior TBS official interview)

Feedback we received identified that stability in the measures is desirable. In an effort to continuously improve the assessment tool, there have been changes within the indicators between each assessment round. In comparing the overall “Strong” rating for each AoM, we noted that 12, albeit minor, changes were made in the rating definition between Round V and VI. Overall, however, we noted that effort has been made between Round V and VI to stabilize the AoMs and the associated lines of enquiry.

Stability of MAF cycle: Currently, the timing of the assessment process is aligned with the COSO process of evaluating deputy head performance, as the final MAF assessment results are released in April, ready for the COSO input in May. However, this timing does not align with the annual planning cycle within departments and agencies. This results in challenges for departments and agencies in integrating the results of the MAF assessments into the operational plans of the upcoming year.

Most stakeholder groups, including deputy heads, TBS senior officials, and departmental MAF contacts, identified the timing of the assessment process as an issue; however, it was further noted that any other time of year would also be challenging due to existing commitments. For example, completing the assessments in the Fall would allow input into the departmental operating plans but also coincide with the preparation of Departmental Performance Report (DPR), which tends to impact the same individuals who coordinate the MAF submissions. As a result of the operational requirements for input into the COSO process and the potential conflicts with existing government cycles, we are not recommending changes to the current cycle and timing of MAF at this time.

5. The current approach of assessing each AoM annually for large departments and agencies does not consider the unique risks and priorities of organizations.

Selection of AoMs to be assessed each year: All large departments are assessed every year against all 21 AoMs and all lines of enquiry. This facilitates comparability of results across the Federal government but does not consider the unique aspects of individual departments and agencies. There are characteristics of organizations for which the impact of the various AoMs might differ, including: size, industry sector, complexity, portfolio relationship with another department and life cycle stage.

Depending on the nature of the department or agency, there are specific AoMs that may have limited applicability; on the other hand, there are some AoMs that would apply to every organization, given the current government priorities. For example, AoM #14 – Asset Management varies in importance given the nature of the organization. In contrast, due to the government-wide priority of accountability and given the role of the deputy head as the Accounting Officer, AoM #17 Financial Management and Control is relevant to all departments and agencies.

International jurisdictions that have models similar to MAF have taken varied approaches to tailoring the indicators. In the UK, the CR indicators are consistent across departments and are not tailored to the specific risk or priorities of the organization. Contrasting that, the CAF was designed to be flexible and allow individual EU countries to tailor the assessment tool.

Due to the public nature of the assessment results, receiving a poor rating in an area of low risk or priority to a department or agency could result in inappropriate decisions related to allocation of resources to improve the subsequent year’s rating. A risk-based or priority based approach to the AoMs, measuring only those that are considered a priority or risk to the individual organization based on their unique characteristics would encourage management to focus on the appropriate areas. 100% of the 20 deputy heads that spoke of a risk-based approach to assessments agreed that this would enable the consideration of the unique risks and priorities of organizations. This would further support the efforts towards streamlining the AoMs. These issues were consistently identified during other stakeholder consultations conducted.

Development of priorities for each department and agency: A common point that was identified by departmental stakeholders was that the results of the MAF assessments that are published on the TBS site are missing context. For purposes of consistency and comparability, context is not considered in the application of the assessment criteria; however, in recent assessment rounds, diligence has been taken to provide appropriate context to the assessment results in the context page provided with the final assessment results.

In the US, where assessments take place quarterly, a “double scorecard” approach is in place to not only assess the organization’s current state but also its progress against its implementation plan.

Interpreting an organization’s performance relative to its circumstances (e.g., life cycle stage, progress towards improvement, size) is critical to get an overall picture; however, setting individual priorities based on the unique circumstances of the organization, sets an expectation of what is achievable by the department/agency and holds the deputy head accountable for performance against these expectations. The identification of these priorities and the performance against them would provide the necessary context to understand the results relative to the unique circumstances of the organization.

6. While the reporting burden associated with MAF has been reduced, there are further opportunities to reduce the impact of the MAF assessment on the departments and agencies.

MAF assessments are completed on an annual basis for all applicable organizations, with the exception of small and micro agencies. Round VI included 21 AoMs and 68 lines of evidence for which submission of documentation was required to allow completeness of assessment. In Round V, a total of 16,96114 documents were submitted to TBS for MAF assessment purposes. As a result of feedback from the post-mortems, TBS committed to reducing the reporting burden. In Round VI, this number had been reduced by 50 per cent, in part due to the introduction of document limits per AoM. This reduction holds true for both the number of documents submitted as well as the total size (in gigabytes) of the documents.

“The reporting burden needs to be assessed . . . to explore options for streamlining the documentation process by maximizing the use of information that is available through other oversight mechanisms / assessments.” (Source: deputy head interview)

In the UK and the US, the current models do not assess all organizations. The focus of the approaches is on the large departments only; limiting the number of organizations assessed. This approach is not recommended as the results of the MAF assessments are used as one input into the COSO process and would impact the comprehensive design of the model.

Despite the positive feedback for these efforts, the reporting burden associated with MAF continues to be a challenge for departments and agencies. Stakeholders believe that the reporting burden, coupled with the public nature of the assessment results, has led to “playing the MAF system,” and has not necessarily resulted in improvements to management practices. A risk or priority based approach to MAF assessments that limit measurement to selected indicators relevant to the individual organization would support the reduction in the reporting burden.

Streamlining reporting requirements: Opportunities for streamlining the assessment process by leveraging existing information was a theme identified by all stakeholder groups. Potential sources to inform MAF were identified including, external Audit Committees, the Auditor General reports and other centrally available, objective evidence. There may also be the opportunity to use other information gathering techniques, e.g., interviews and workshops, to gather evidence on which to complete an assessment, where applicable.

As a progressive step, TBS has taken the initiative to streamline the element of People for Round VII. The approach taken has resulted in a consolidation of the people management elements currently reflected in AoM #1, 10, 11 and 21 into one AoM called “People Management”15. The process has further been streamlined to develop measures based on eight existing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that do not require any additional reporting requirements beyond what is currently available. The approach taken was to identify all sources of data requests and all information currently available. Indicators of performance were then developed using the existing information. This approach may be considered for other AoMs in conjunction with the development of “golden rules” (outlined in section 4 "Recommendations" to this report) within the performance assessment framework.

Consistency of available guidance for indicators: The level of guidance provided to organizations to support their understanding of the reporting expectations is inconsistent across the indicators. For some AoMs, the level of guidance materials provided to departments and agencies is very detailed and prescriptive, which can add to the complexity of the process. For large departments, each AoM can be allocated to individual senior executives; in contrast, smaller agencies must rely on the limited resources they have to respond to MAF and as such, the amount of guidance materials can seem overwhelming and directly impact the acceptance and satisfaction with the approach. Development of “golden rules” or common principles, including simplicity of guidance documentation with a consistent look and feel, should provide the necessary parameters and allow for consistency of guidance across AoMs.

7. The subjectivity of the MAF assessments is a result of a significant number of qualitative indicators built into the assessment approach.

Subjectivity of indicators and rating definitions: For those indicators that are necessarily qualitative in nature (i.e. without quantitative measures), a significant component of the assessment relies on judgment by analysts, reviewers and executives within TBS. For example, AoM #8 “Managing Organizational Change” attempts to measure the “extent to which the organization is engaged when undertaking change management”. AoM #1 “Values-Based Leadership and Organizational Culture” seeks to measure that “organizational culture is reflective of public service values and ethics”. In these instances, there is a risk that there will be challenges in supporting decisions and ensuring consistency in the application of judgment.

Qualitative measures are a necessary way of measuring specific elements of managerial performance. Necessary subjectivity that is built into the assessment process should nonetheless be accompanied by well-defined measures that increase the likelihood of consistency across organizations. In our review of criteria supporting AoM ratings, we noted that the rating definitions used to assess the evidence are not always well defined, nor are they supplemented with examples or baseline standards to ensure consistency across AoMs. As an example, when rating an organization for Line of Evidence 1.1 “Leadership demonstration of strong public service values and ethics”, the difference between receiving an ‘opportunity for improvement’ and receiving an ‘acceptable’ rating is the difference between whether the task was performed ‘sporadically’ and ‘regularly’. The rating criteria does not define the qualitative indicator (i.e. how often is ‘regularly’), nor is there a measure of effectiveness provided (i.e. is performing a task ‘regularly’ appropriate to the circumstances for a certain department). By comparison, we noted in our international research that the CAF approach in the EU includes provisions of examples to support consistency in the application of the measures.

Perceived negative connotation of the acceptable rating: Within MAF, each department is given a rating by AoM. The rating scale, which is used for all AoMs, comprises four levels:

- Strong;

- Acceptable;

- Opportunity for Improvement; and

- Attention Required.

Through the course of our evaluation, several departmental stakeholders identified that the rating terminology of “acceptable” was not well received or considered appropriate as it is perceived to have a negative connotation. Since an “acceptable” rating is meant to be positive, based on the associated narratives provided by TBS, there may be an opportunity to adopt alternative terminology to represent this rating on the assessment scale. For example, the UK CR uses the label “well placed” as the next rating before “strong”.

Inconsistency of scoring across indicators: While a rating definition is provided for each line of evidence, a scoring methodology is applied to each AoM to arrive at an overall score by AoM. The score and weighting system used to assign the AoM rating is not consistent across the AoMs. Approaches used include weighted average, a straight average or a subjective approach. Using a consistent framework for weighting assessment scores is considered a best practice, which would further improve the transparency, understanding and acceptance of AoM ratings by departments and agencies.

There is an opportunity to harmonize the indicators and the associated rating criteria to increase the consistency of assessment given the qualitative nature of indicators designed to measure managerial performance. The development of “golden rules” for all AoMs, including measurable indicators that use a standard scoring approach, would provide parameters to the AoM leads within TBS when developing indicators and rating definitions.

8. Many of the lines of evidence from Round VI are process-based, which do not measure effectiveness of the outcomes resulting from the process.

“MAF is measuring process, not management outcome; MAF tells us WHAT but needs to go further to say HOW to improve.” (Source: deputy head interview)

Our evaluation identified that out of the 68 lines of evidence in Round VI, 24 (35%) are primarily process-based; the remaining lines of evidence attempt to measure results/outcomes or measure compliance to policy requirements. Process-based indicators may only measure the process associated with the infrastructure and do not necessarily attempt to integrate measures of the effectiveness or the outcomes of the decisions that have been made.

By using process-based indicators to measure managerial performance, there is an inherent assumption made that the process itself will lead to the achievement of results. This assumption can only be made; however, if it can be determined that the process is optimal for every situation; it is difficult to measure managerial performance using process-based indicators due to this uncertainty factor. Outcome-based indicators increase the ability to assess whether the management practices had an impact on the quality of decisions and actions. The use of a logic model can be leveraged to determine these indicators.

As an example, one organization confirmed that to meet the requirements of MAF, they formalized their previously informal committee structure. As a result, each committee developed terms of reference and formalized the process. While this was done and was recognized by the MAF score, senior management questioned whether it changed anything regarding the actual effectiveness or outcomes of the mechanism.

The development of “golden rules” for all AoMs, including outcome/results-based indicators, would provide parameters to the AoM leads within TBS when developing indicators and rating definitions.

3.4 Is MAF Cost Effective?

“Is MAF cost effective? Two years ago I would have said no. We’re getting there now. We’re starting to see more efficiency and effectiveness in the assessment and more benefits on the managerial side...” (Source: deputy head interview)

The results of our analysis indicate that while improvements have been made in recent rounds to address the issue of the reporting burden and thus improving the efficiency of the MAF process, we think there are additional opportunities to reduce the level of effort required for organizations to provide evidence as part of the MAF process. However, based on the limitations of the costing information available, a conclusion on the costs and the cost effectiveness of MAF cannot be determined. The section below provides an analysis of the cost information that was available. Also included are two examples regarding benefits departments have identified resulting from MAF.

9. Our consultations indicated that most departments and agencies were unsure of the cost effectiveness of MAF.

Example: Agriculture and Agri-food Canada (AAFC)

AAFC historically has struggled with the capacity to manage the required TB submissions, as a result of the increased funding provided to the department resulting from the 2006 Budget. This resulted in a MAF result of “attention required” for AoM 5 in Round IV.

Significant efforts were undertaken by the department to improve the management of TB submissions, including the development of a protocol and criteria to differentiate between priority and less critical TB submissions.

This reduced the number of submissions that required compressed timelines and allowed sufficient time for the department to develop good quality TB submissions.

Further, a control unit within the department has been established to enhance oversight, the challenge function and quality control. All these actions have resulted in an improved rating for AoM 5 since Round IV.

Our key findings resulting from our consultations with departments and agencies are that:

- While a majority of deputy heads interviewed indicated that there is a significant level of effort required within the department to report on MAF, there are qualitative benefits being realized in the departments as a result of MAF.

- Deputy heads acknowledged efforts to address reporting burden and ask for continued efforts in this area, e.g., reduction in documentation requirements, tools, guidelines and the best practices conference were well received.

- From the perspective of small departments and agencies, several interviewees indicated that the level of effort was not justifiable given the limited capacity of their organizations.

- Our evidence suggests that there is strong support for streamlining the number of AoMs and making the process more risk-based so as to reduce the level of effort required by departments/agencies to respond to MAF requirements.