ARCHIVED - The Financial Administration Act: Responding to Non-compliance - Meeting the Expectations of Canadians

This page has been archived.

This page has been archived.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

| Related Documents |

-Management in the Government of Canada: A Commitment to Continuous Improvement -Review of the Responsibilities and Accountabilities of Ministers and Senior Officials |

Table of Contents

1. Overview of the Financial Administration Act

2. Managing in the Public Service

2.1 What is mismanagement?

2.2 Better rule making: Overhaul of the management policy suite

2.3 The special duties and obligations of public service employees

2.4 Public service culture and values

2.5 Consequences and implications of non-compliance and mismanagement

2.6 Key conclusions of the review of non-compliance in the context of the FAA

4. Disciplinary and Administrative Sanctions

4.1 What constitutes "discipline"?

4.2 Standards of conduct

4.3 Discipline as part of administrative responses to individual behaviour

4.4 A look at disciplinary sanctions and administrative responses for specific groups of

public service employees

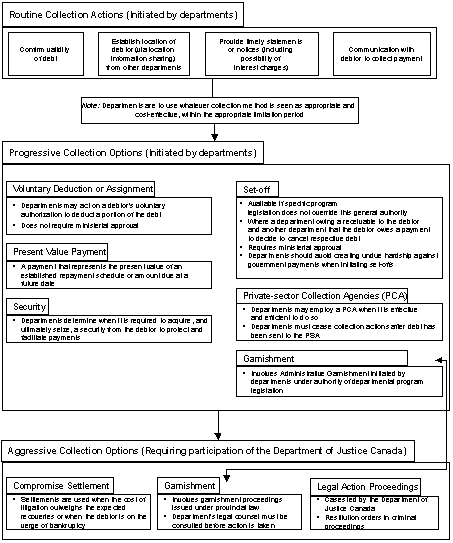

6.1 The government's approach to debt recovery

6.2 Debt recovery in other jurisdictions

6.3 Facilitating debt recovery

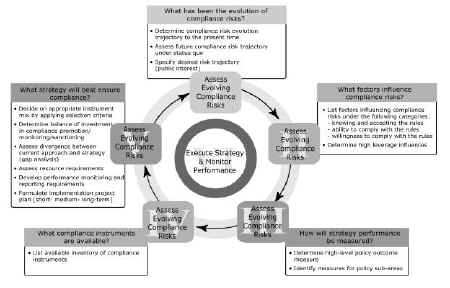

7. Fostering Better Compliance with Management Rules

7.1 A compliance framework for the Government of Canada

7.2 Why? A study of factors underlying non‑compliance

7.3 Basing compliance strategies on risks

Appendix A: List of Subject Matter Specialists Consulted

Appendix B: Disciplinary and Non-disciplinary Authorities

Appendix C: Debt Collection

Executive Summary

Managers in the federal Public Service serve in an institution created and governed by a complex array of statutes, regulations, policies, and directives. They operate in an environment of increasingly intense scrutiny and accelerated changes driven by technology, program reviews, and public and political expectations for service improvements. These factors, combined with the growing institutional complexity and risks and concerns expressed by the Auditor General of Canada, led to this review of mechanisms that operate in response to compliance with the Financial Administration Act (FAA) and the recovery of lost public funds.

The review's terms of reference were framed by the purpose and intent of the FAA, which finds its origins in the earlier days of the confederation. The FAA sets out the core legal framework within which public sector managers must manage.

This review has provided the government with a thorough and comprehensive look at the complex issues surrounding compliance and sanctions under the FAA and related policies. While public attention has focussed on recent instances of mismanagement, it is clear that the vast majority of those charged with public sector management responsibilities carry out their duties with integrity and honesty. Comparative research also confirms that Canada is on par with other jurisdictions in the areas of criminal sanctions, debt recovery, investigations, and discipline.

Furthermore, the review has provided a better understanding of opportunities to improve the integrated policies, and statutes that comprise the compliance framework for the FAA and set the context for managing in the Public Service.

A number of broad and important conclusions and understandings need to be emphasized:

- The principles behind the legislative and administrative frameworks are sound. The difficulty arises from the accumulation of rules and policies, etc. This complexity contributes to confusion and errors.

- "Mismanagement" includes a wide variety of behaviours ranging from a mistake or error up to and including criminal activity such as theft or fraud. Regardless of where mismanagement falls on the spectrum, appropriate tools and responses are generally available.

- Education and training at all levels of the Public Service are of paramount importance both to addressing mismanagement and to helping public service employees do their jobs properly.

- Consistency is crucial in addressing mismanagement. Sanctions must always be applied with the primary goal of restoring compliance.

Managers must be held accountable for mismanagement that falls within their area of responsibility. Accountability must start from the top. Good examples must be set to encourage confidence and to reinforce the trust that underlies the relationship between the Government of Canada as employer and its employees.

Most importantly, any response, be it carrying out an investigation or taking remedial action, must be conducted rapidly and transparently. The results must be communicated effectively in order to enhance confidence in the government's compliance framework.

Recommendations from this review have been incorporated into the paper Management in the Government of Canada: A Commitment to Continuous Improvement.

Introduction

The Government of Canada has made a commitment to restoring trust and accountability in government. On December 12, 2003, the government announced a series of initiatives to attain these objectives. Since that time, the government has made strides in strengthening oversight, accountability, and management across the public sector.

On February 10, 2004, the government announced measures aimed at strengthening transparency and accountability across the public sector. These measures included improving oversight activities, principally at the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (the Secretariat), and the launch of three reviews directed at specific areas of public sector management, including one on the compliance and sanction regime under the Financial Administration Act (FAA).

This review's terms of reference covered three broad areas:

- review of the tools and mechanisms available to the government to prevent and deter instances of mismanagement or the disregard of related laws and directives;

- review of compliance and sanction regimes applicable to current employees of the Public Service, the broader public sector, as well as former employees; and

- review of investigative processes and approaches, including those used in seeking recovery of public funds, to determine if and how they can be enhanced.

On March 24, 2004, the government released the Action Plan for Strengthening Public Sector Management and reaffirmed its commitment to strengthen the rules governing compliance with management principles. The Action Plan included a full review of the government's measures for dealing with all aspects of mismanagement or rule breaking. The scope of the review includes prevention and deterrence tools and mechanisms as well as options available to the government, investigative processes and approaches, and recovery of public funds. The 2005 budget documents provided an update on these initiatives.

Most of the research and consultations for the review were conducted in 2004. This served as a basis for discussions and analysis that supported an important part of the management improvement agenda. This report sets out the context within which elements of the Action Plan related to compliance, investigation, and consequences may be considered.

A Word on Methodology

The work underlying this report was done through a series of modules conducted by members of a review team assembled from different areas within the government. Experts in the areas of labour relations, management, and financial management were brought in, along with lawyers with experience in criminal law, labour and employment law, and instrument choice.

The review team consulted subject matter specialists in areas including financial management, law enforcement, and labour relations using methods such as individual discussions and focus groups. Members from the executive cadre down to middle managers also participated in these consultations. A review of practices in other jurisdictions, within Canada and abroad, offered additional insights. The team also conducted both legal and academic research to gain a better understanding of the current state of the law with respect to these issues and of the issues themselves. A list of the organizations and persons consulted is found in Appendix A.

There is no comprehensive empirical evidence concerning the degree or number of cases of non‑compliance or mismanagement in the federal government. The information on non‑compliance and mismanagement used as part of this review was gleaned from reports prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada and from anecdotal evidence and information obtained through internal consultation.

1. Overview of the Financial Administration Act

The Public Service of Canada is governed by a legislative framework that sets out the formal rules for the administration and management of the government. This section illustrates that framework in three key areas: financial administration and management of assets, human resources, and information management.

The Financial Administration Act (FAA) is the cornerstone of the legal framework for general financial management and accountability of public service organizations and Crown corporations. It sets out a series of fundamental principles on the manner in which government spending may be approved, expenditures can be made, revenues obtained, and funds borrowed.

The FAA also provides a procedure for the internal control of funds allocated to departments and agencies by Parliament and for the preparation of the Public Accounts that contain the government's annual statement of expenses and revenues. The financial statements are presented to the Auditor General of Canada, who provides an independent opinion on them to the House of Commons.

The Minister of Finance is given the management of the Consolidated Revenue Fund, into which all revenues must be paid and from which expenditures are paid with parliamentary approval.

The FAA also establishes the Treasury Board, a committee of Cabinet composed of at least six ministers, including its President and the Minister of Finance. The FAA allows the Treasury Board to adopt administrative policies for the Government of Canada and gives it specific authority to issue directions in various areas related to the management and control of funds. Thus, while the FAA does not encompass all of the rules and principles governing public management, it serves as the principal source of management authority for the Public Service. For this reason, it has led to the definition of the parameters for this review. The Treasury Board also carries out other related functions; notably, it acts as the employer of public service employees engaged in core public administration and plays a key role in real property matters. The Treasury Board may act by approving general or specific policies or directives or by issuing non‑binding documents providing guidance and benchmarks.

For the most part, the Treasury Board uses the authorities granted (primarily) under the FAA to issue policies that are binding upon the administration. There are currently about 411 instruments issued by the Treasury Board, including policies, directives, and guidelines.

The FAA also authorizes the passing of regulations. While from the public service perspective the policies are no less binding than the regulations, the breach of regulations is liable to attract sanctions that would not be applicable to the breach of published directives or instruments. Regulations, like legislation, are official, published instruments and, in certain circumstances, they also affect third parties. There are currently 13 regulations of general application adopted pursuant to the provisions of the FAA.

Finally, the FAA also sets specific rules itself, most notably in the areas of collection, management, and spending of public funds.

The FAA imposes rights and duties on ministers and directly on deputy heads in relation to the institutions they manage. These include, notably, the obligation for a deputy head to establish procedures and maintain records respecting the control of financial commitments chargeable to public funds, the fact that only a minister or his or her delegate can request the issuance of a payment, and that before a payment is issued in return for work, goods, or services, the deputy of a minister (or another delegate) must certify that the work has been performed, the goods received, or the services rendered (sections 32, 33, 34).

Departments are primarily responsible and accountable for the following:

- the expenditure of funds and management of assets that they have been allocated;

- delivering the results that they commit to achieving with the resources they have been allocated; and

- meeting the management expectations according to performance indicators in the Management Accountability Framework (MAF) for performance reporting and accountability, which sets out a rigorous regime of managerial expectations.

Departments, as led by their deputy heads, are also responsible for implementing appropriate management processes, systems, and instruments to deliver their management duties and obligations, and monitor their performance.

An appropriation act is the vehicle through which Parliament provides spending authority to the government on an annual basis. It is how Parliament discharges its responsibility through section 26 of the FAA and section 53 of the Constitution Act, 1867. About 33 per cent of spending monies are acquired in this manner. Money is also acquired through statutory appropriation, which means that approval for funds is embedded in legislation and does not have to be sought annually.

A number of other statutes are instrumental to human resources management in the federal Public Service:

- the Public Service Staff Relations Act (PSSRA);

- the Public Service Employment Act;

- the Public Service Modernization Act;

- the Canada Labour Code;

- the Canadian Human Rights Act; and

- the Employment Equity Act.

The PSSRA establishes a framework for the certification of bargaining agents, a collective bargaining regime, and the provision of essential services in case of strikes. It also provides a right to grieve discipline and any action affecting terms and conditions of employment. Regulations under the PSSRA set out the grievance and adjudication processes. The PSSRA also articulates prohibited conduct that may constitute an unfair labour practice as well as a bargaining agent's duty to fairly represent its members.[1] Collective agreements concluded pursuant to provisions of the PSSRA are legally binding on the employer and its representatives, the bargaining agent, and the employees subject to it.

The Public Service Employment Act sets out the rules and principles governing the staffing of positions in the Public Service. Built on the merit principle, with a view to ensure and maintain the political neutrality of the Public Service, it strives to ensure fairness and equity in the manner in which positions are being staffed.

Both statutes and their underlying principles were reviewed as part of the Public Service Modernization Initiative. The Public Service Modernization Act reissues both of these acts.

Part II of the Canada Labour Code governs occupational health and safety in the workplace. It affects both public and private sector workers under federal jurisdiction. It further establishes fundamental employee safety rights and sets out the roles of health and safety committees and officers as well as procedures for determining whether a danger in the workplace exists.

The Canadian Human Rights Act prohibits discrimination and harassment based on a series of enumerated grounds. These include sex, age, disability, ethnic origin, and sexual orientation. The Canadian Human Rights Act mandates the Canadian Human Rights Commission to receive and inquire into complaints and, ultimately, refer them to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal.

The Employment Equity Act was implemented to achieve equality in the workplace so that no person would be denied employment opportunities or benefits for reasons unrelated to his or her abilities. It also aims to correct the disadvantage in employment experienced by women, Aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities, and members of visible minority groups by giving effect to the principle that employment equity means not only treating persons in the same way, but also requires special measures and the accommodation of differences. The Employment Equity Act applies to employers in the private and public sector and sets out the employers' obligations in support of employment equity.

Information management is governed by three main pieces of legislation: the Privacy Act, the Access to Information Act, and the Library and Archives of Canada Act.

The Privacy Act obliges managers to protect the privacy of employees and to retain information pertaining to them. Under the Privacy Act, the personal information of an employee can, upon request, be disclosed to that individual, subject to any applicable exemptions. The Access to Information Act requires safekeeping of most information created or obtained by the government (it creates a criminal offence for deliberately destroying information likely to be requested). Subject to some specific exemptions, the Access to Information Act requires officials to produce information upon request by members of the public. The Library and Archives of Canada Act dictates the rules governing retention periods for documents. Each of these statutes is accompanied by regulations. The Secretariat provides supplemental guidelines and policies to assist institutions with interpretation of the Privacy Act and the Access to Information Act.

2. Managing in the Public Service

"Good management" is not just the application of a series of rules and legal instruments, and "mismanagement" cannot be simply defined as a failure to apply management rules. There is no single instrument to guide public service managers: the rules and principles by which they must operate are scattered in a variety of statutes, regulations authorized by those statutes, and, as described above, numerous policies and directives applicable to the internal administration of government.

Good public sector management requires sound judgment that is well grounded in ethics, values, and principles and a desire to uphold the rule of law and pursue the public interest. Rules, whether regulations, policies, guidelines, or directives, should be understood and respected. Respect for the rules does not preclude changing them to enhance program delivery or creating new ones that respect fundamental values. The environment in which public service employees manage is in constant evolution. Drivers of change include a more complex policy environment, program review and its ensuing effects on specialist communities supporting managers, along with additional layers of rules dealing with specific issues. Public service employees, particularly at senior levels, are often caught in organizational paradoxes amplified by the nature of the institution: It is characterized by frequent change in policy directives and the need to constantly reconcile a broad range of interests and values. At the same time, technology has raised expectations for faster decision making and increased transparency, while access to information legislation has, in turn, fuelled a demand for more information, delivered faster.

This review was primarily conducted with financial management as a focus. Much of the analysis and many of the conclusions apply to the broader scope of management responsibilities, notably to those related to human resources and information, where the same high standard of ethical behaviour is expected to be applied.

2.1 What is mismanagement?

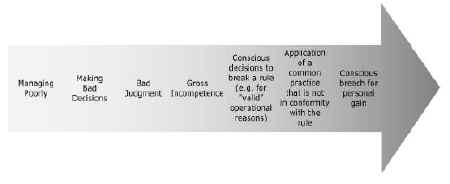

Dictionaries define "mismanagement" as doing something badly, improperly, wrongly, carelessly, incompetently, or inefficiently. Mismanagement could conceivably cover a range of actions from a simple mistake in performing an administrative task to a deliberate transgression of relevant laws and related policies. In some cases, it could involve criminal behaviour such as theft, fraud, breach of trust, and conspiracy. A continuum is illustrated below.

Figure 1. Range of Mismanagement Actions

Given the scope of the issues covered here, no single all-encompassing definition of "mismanagement" is adequate. For example, both the discussions on criminal sanctions and disciplinary regimes require more precise views. On the other hand, discussion of approaches to promote compliance can accommodate a broader definition. For these reasons, the review has not attempted to arrive at a precise definition. This review has adopted, as a working concept of mismanagement, those situations where a public service employee fails to follow the rules set by the framework of management instruments created by the FAA.

2.2 Better rule making: Overhaul of the management

policy suite

It is intuitive that increased knowledge of management rules does, in turn, increase compliance. As noted at the outset, there are hundreds of Treasury Board instruments imposing specific responsibilities and accountabilities. Confusion arises because management policies lack coherence, speak to varying levels within government, or use slightly different language. They can at times present a "siloed" approach to problem resolution rather than a holistic one.

The Secretariat and the Public Service Human Resources Management Agency of Canada are working to streamline and simplify the Treasury Board management policy suite. This is also an objective of the Public Service Modernization Act directed, in part, at making the staffing process more efficient.

Managing in the government will never be simple. The Treasury Board's policy review effort is striving for a coherent view of the rules for managers. The goal is to make policies part of an overhauled global guidance system for public service employees—a system that will make management rules come to life for managers and practitioners—improving coherence and easing compliance, while contributing to an environment where employees willingly and systematically pursue compliance.

2.3 The special duties and obligations of public service employees

Public service employees have special responsibilities. By virtue of holding a public service position, employees and office holders are entrusted with a series of special obligations that differ from those found in private sector employment relationships. This results in specific duties and commitments for these employees.

The constitutional conventions relating to the role of the Public Service within the cabinet‑parliamentary system stress the value of a non‑partisan, professional, and permanent public service appointed and operated on the basis of merit and competence. This public service is intended to provide intelligent and objective policy advice to ministers and deliver programs in an efficient and impartial manner.

In 1985, the Supreme Court of Canada noted that the fundamental task of the federal Public Service is to administer and implement policy, saying:

In order to do this well, the public service must employ people with certain important characteristics. Knowledge is one, fairness another, integrity a third. […] The tradition [surrounding our public service] emphasizes the characteristics of impartiality, neutrality, fairness and integrity.[2]

The 1996 Tait report, A Strong Foundation: Report of the Task Force on Public Service Values and Ethics, set out some of the factors underlying the trust placed in public service employees:

Every day, in myriad ways, public servants make decisions and take actions that affect the lives and interests of Canadians: they handle private and confidential information, provide help and service, manage and account for public funds, answer calls from people at risk. Because public servants hold such a significant public trust, ethical values must necessarily have a heightened importance for them.

A public organization does not and cannot enjoy the "flexibilities" of private sector organizations. It will always have to meet higher standards of transparency and due process in order to allay any fears of favouritism, whether internal or external, in performing its duties under its position of trust and in its use of public funds.

The expectations placed on public service employees are highlighted:

[…] wherever we find ourselves in the public service, and at whatever levels, we enjoy the deep privileges of public service—the opportunity to serve and help our country—and the obligations of leadership and initiative that go with them. We do not have to, and should not, wait for signals from others before undertaking the great tasks of public service leadership: exercising imagination, creativity and vigilance for the public good and caring for the people entrusted to our charge.[3]

The Supreme Court of Canada took a similar view in a 1996 decision:

Protecting the integrity of government is crucial to the proper functioning of a democratic system. […] Preserving the appearance of integrity, and the fact that the government is fairly dispensing justice, are, in this context, as important as the fact that the government possesses actual integrity and dispenses actual justice. […] given the heavy trust and responsibility taken on by the holding of a public office or employ, it is appropriate that government officials are correspondingly held to codes of conduct which, for an ordinary person, would be quite severe.[4]

Clearly, in acting on behalf of their ministers, public service employees, and particularly those in the senior ranks of the Public Service, are burdened with a set of responsibilities that is unique and very different from those of their private sector counterparts. These responsibilities are accompanied by a set of rules, the breach of which would not necessarily attract any reaction in the private sector but may well constitute "mismanagement" in the public sector.

2.4 Public service culture and values

Historically, the Public Service of Canada has evolved into an organization grounded in solid ethical principles and sound values. The public service values, as set out in the Tait report, provide a strong framework to guide managers and employees. Furthermore, a number of current initiatives reinforce a values-based public service culture. For example, the government "whistle‑blower" bill (protecting public service employees who disclose wrongdoings) introduced in 2004 highlights values and proposes a Charter of Values of Public Service.

In December 2003, the responsibility for public service values and ethics was given to the Public Service Human Resources Management Agency of Canada. Among the Agency's priorities was creating widespread awareness, understanding, and application of public service values and ethics, including obligations under the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Service as well as supporting departments and agencies in meeting their commitments by establishing performance indicators, providing a "roadmap" for assessing and improving values and ethics results, and implementing measurement and evaluation strategies, including surveys.

An evolving public service needs to maintain and reinforce a strong ethical compass, but balance is critical. A management approach exclusively based on values and principles would not only be impractical but also unfair to public service employees. The renewal of the management policy suite will provide a set of clear directions within which public service employees will be able to work, while being inspired and guided by their values and sense of ethics.

As noted by Peter Aucoin, a professional public service can articulate and communicate what its values are and can govern itself accordingly. This is not achieved only by getting the right legislative framework in place or by having the right attitudes:

[…] Rather, it is dependent, first and foremost, upon both the individual and collective willingness to exercise professional judgment, that is to take action when managers or staff do not behave in ways that accord with public service values and ethics and to reward those who do.[5]

2.5 Consequences and implications of non-compliance and mismanagement

In general, unresolved issues of non-compliance and mismanagement weaken the public's trust in government as a protector of the public interest. (Even when such cases are not made public, mismanagement that results in a loss or waste of resources reduces the government's capacity to do its job). Neither the various reports of the Auditor General of Canada nor anecdotal evidence of cases of mismanagement point to an insufficiency of rules. The evidence points instead to a periodic or occasional lack of compliance—by officials and departments—with some of the rules.

In extreme cases, non-compliance can erode the reputation of the Public Service. Canadians rightly expect managers and public service employees follow the rules. Their confidence when dealing with the Public Service may be adversely affected if non-compliance were ever to be seen as widespread. Even the government's reputation might suffer if it was perceived that widespread or serious non-compliance was left unchecked. In the last few years, in fact, there has been evidence of a growing public perception of declining ethics and professionalism in governments.

In these extreme circumstances, instances of non-compliance can undermine the government's role as a lawmaker and regulator. Canadians who obey the law—the vast majority—do so because they view the legal authorities they deal with as having a legitimate right to set and enforce certain behaviours that are in the public interest. A governing institution that appears to be unable to put its own house in order may well run into issues of credibility.

2.6 Key conclusions of the review of non-compliance in the context of the FAA

Essentially the FAA itself does most of what is needed to set a legal framework for public sector management.

At the time this exercise was initiated, a number of critical issues had been identified for review:

- Whether the government has the right instruments to conduct investigations into questions of mismanagement. If not, this would hamper the government's ability to address these situations. The review also identified a number of enhancements to the current regime.

- Once mismanagement is established and disciplinary and administrative responses are warranted, whether the right sanctions existed and managers were able to use them, giving also specific attention to some employees in particular situations (executives, former employees, public office holders, Crown corporation office holders, employees of Crown corporations). The review concluded that the existing regime possesses the basics. For the most part, the government needs to build its capacity to use them as well as to better promote and recognize management excellence in the senior cadre of the Public Service.

- When the situations of mismanagement are serious, whether criminal sanctions are used and if not, why. The review confirmed that the FAA's criminal provisions have practically never been used but that similar offences found in the Criminal Code are used occasionally to prosecute public service employees for actions related to their functions, normally in relation to instances of theft, fraud, or corruption.

- Finally, where the mismanagement led to the loss of funds, whether the government's procedures for recovering those funds are adequate. The review found that the systems and processes in place were complete, albeit somewhat complex. It concluded that enhancements could be made to facilitate their application.

The review also examined related areas that were identified as important, including the creation of a compliance framework.

3. Investigations

The review examined options and ways to strengthen administrative investigative processes applied to instances of possible mismanagement. It examined those processes principally as they relate to the imposition of disciplinary sanctions. During the review, staff relations officers, consultants who have been involved in investigations on behalf of the government, managers, lawyers who have used investigation products, police forces and Crown prosecutors, and departmental investigators were consulted and bargaining agents were invited to participate in discussions on the subject.

Within the broader framework of addressing mismanagement of funds and non-compliance in the federal Public Service, the investigatory process is crucial. Investigations serve to substantiate allegations (or not, depending on the evidence) and to identify wrongdoers, by way of gathering evidence through interviews and document compilation. They also serve to determine causal or facilitating factors for the misconduct, thereby playing a role in preventing reoccurrence of the situation that may have led to the misconduct having been committed. Finally, a promptly and properly conducted investigation will raise employee confidence in the employer and morale in the workplace.

Treasury Board publications provide limited guidance in the area of investigations. In fact, other than the Treasury Board Guidelines for Discipline, there are no government-wide policies or procedures on administrative investigations. Over time, however, a variety of duties and obligations have been established for both the employer and the employee, through accepted practices, clauses in collective agreements, and decisions of administrative tribunals, principally the Public Service Labour Relations Board.

The employer's duties and obligations encompass such things as promptly investigating in the event of an incident or a complaint. All avenues of information and evidence must be explored during the process. The employer must also give sufficient notice of the investigation to the employee. This notice must contain specific information on the allegations and indicate the consequences of an adverse decision. Employees have the duty to participate in meetings and to provide all relevant information pertaining to the employee's possible defence; they also have the obligation not to cause undue delays.

Through the consultations and interviews held in the review process, a number of areas where improvement would be desirable were identified:

- Managers trained in the conduct of investigations or qualified investigators are not always available. This is particularly an issue outside of large urban areas or within smaller operations.

- Staff relations personnel and investigators called upon to perform administrative investigations do not always have sufficient training or uniform guidelines.

- It is not uncommon to have both criminal and administrative investigations occurring simultaneously or one occurring immediately after the other. This leads to confusion about the rights and responsibilities of managers in regard to the administrative investigation.

- Investigations are not always carried out in a timely manner, in part because of the other reasons outlined here.

- Investigators and managers do not always have access to or knowledge of the findings of other government entities examining the same events (internal audits, various ombudsmen, the Auditor General of Canada, security investigations, disclosure officers, etc.), nor are all the players equally knowledgeable about each other's role and methods.

Perhaps the biggest shortcoming in the area of administrative investigation is the unequal access to investigators trained in the conduct of administrative investigations and knowledgeable about the Public Service. Many departments rely on managers to conduct complex investigations. Others rely on investigators who have been trained as police officers and who are not familiar with the particular nature of administrative investigations.

4. Disciplinary and Administrative Sanctions

The review examined Treasury Board policies, guidelines, and the management framework governing discipline within the Public Service to determine if they could be strengthened. In seeking to assess the strength of the regime, consultations were carried out in a variety of organizations, with human resources professionals, and with management. Bargaining agents were also invited to participate in the review.

Disciplinary sanctions are primarily aimed at individuals. Imposing personal consequences can be achieved via disciplinary or administrative measures. This should not suggest that institutions are absolved from responsibility when mismanagement occurs. A strong institutional lens—including examination of systemic circumstances that contribute to individual mismanagement—is an important element of the government's Action Plan. In many cases, appropriate responses to non‑compliance would be aimed, wholly or in part, at the institution.

A minister's accountability relates principally to the general direction of a department—to its policies and programs. It entails representing the department before Parliament, guiding legislation relating to the department's work through the legislative process, ensuring acceptance of departmental estimates of proposed expenditures, and explaining and defending the department's policies and practices. Ministers are also accountable for the overall quality of departmental management. The more administrative aspects of accountability involve management and the soundness of departmental finances. A further aspect of this control mechanism is, of course, the allocation of responsibility for maladministration, misconduct, or unexpected results of governance.

The employment sanction systems, both administrative and disciplinary, allow ministers to provide assurance to Parliament and the public that systems are in place to respond in a progressive and appropriate manner to instances of inappropriate conduct by public service employees. This includes seeking out the causes of the misconduct, taking appropriate corrective action, and neutralizing any contributing factors that come to light.

Many tend to view the role and functions of the Treasury Board in its role of public employer as similar to those of private sector employers. In fact, the two regimes were vastly different for most of the first 100 years of Confederation when public servants where occupying offices truly at the pleasure of Her Majesty. Over time, the values, ethics, and policies governing behaviour—and accountability—for public service workers have evolved into a complex set of special duties and obligations, some of which were inspired by private sector practices but a large part of which still depend on the particularities of the public service environment. Similarly, disciplinary standards and practices have changed over time; the authority to impose discipline is now shared among deputy heads, heads of separate employers, and the Treasury Board.

4.1 What constitutes "discipline"?

Disciplinary actions in the governmentManagers have a number of responses at their disposal:

|

Disciplinary actions are intended to motivate employees to accept those rules and standards of conduct that are desirable or necessary in achieving the goals and objectives of the organization. A disciplinary system also serves to punish the employee and is a mechanism of deterrence; that is, it is intended to prevent any other employee from engaging in the misconduct. At the extreme end of the spectrum, when circumstances warrant and the bond of trust has been irreparably severed, a disciplinary system will support termination of employment.

Discipline responds to fault, either willful wrongdoing or culpable negligence. It is not used to respond to instances of incompetence or incapacity, unless, of course, this is due to factors under the employee's control.

The FAA, the Public Service Labour Relations Act, and Treasury Board policies, along with case law and rules generally accepted in the field of staff relations, do provide a framework of rules and obligations in imposing discipline, from investigations and interviews to disciplinary hearing and documentation. They provide for steps in determining misconduct and disciplinary action and provide various redress procedures to those who are disciplined. Disciplinary action may be the subject of a grievance. A grievance complaining of discipline causing a financial penalty, suspension, or termination may also be referred to adjudication. Disciplinary action will be judged against the standard of cause. Cause requires an adjudicator to determine if misconduct or misbehaviour has occurred that justifies a disciplinary response and, if so, whether the misconduct in question warrants the particular action (or penalty) taken, considering all of the circumstances. If an adjudicator finds that the employee's conduct did not constitute misconduct or that the penalty was excessive, the adjudicator will normally rescind it.

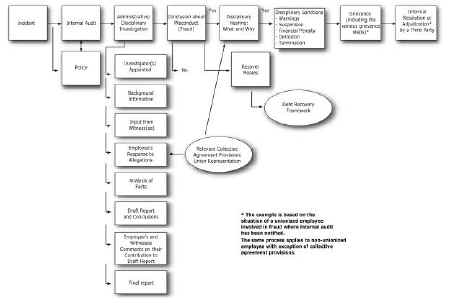

Figure 2 illustrates the steps of the standard disciplinary process used in the government chronologically.

Figure 2. The Disciplinary Process in the Government of Canada

4.2 Standards of conduct

Employees are responsible at all times for conforming to established standards of conduct, implicit or explicit. There are several Treasury Board instruments that establish standards of conduct in specific areas: the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Service, the Policy on the Internal Disclosure of Information Concerning Wrongdoing in the Workplace, and the Policy on Losses of Money and Offenses and Other Illegal Acts Against the Crown. These recognize and reflect the unique nature of public service employment and employees' special obligations related to impartiality, honesty, loyalty, and confidentiality. Moreover, the Conflict of Interest and Post-employment Code for Public Office Holders was created to enhance public confidence in the integrity of public office holders and the decision-making process in government. Other standards of conduct (that are not based on unique requirements of the Public Service but rather on good management practices) are established in such policies as the Policy on the Prevention and Resolution of Harassment in the Workplace.

Department-specific standards of conduct may also be set. For this exercise, deputy heads are cautioned by the Treasury Board against attempting to provide an exhaustive definition of what constitutes misconduct in order to ensure that they retain sufficient flexibility to deal with any type of disciplinary matter that might arise.

Many other types of employment-related misconduct are implied, such as insubordination. Because certain conduct is implicit in the employment context (that is, fundamental conduct that is compatible with an employee's discharge of the duties and responsibilities of his or her employment), it is not necessary for it to have been spelled out expressly in a policy.

Violation of work-related policies may also constitute misconduct, for example, breach of the requirements of a policy on Internet use or a travel policy.

Before imposing discipline, the department must ensure that the employee has received advance notice of the expected standards of conduct or must reasonably establish that the employee ought to have known about the standards of conduct. Expectations concerning what the employee should be expected to know arise from the employee's position, training, and certification; position mandate and responsibilities; work experience; and efforts to cover up as well as common sense; objective reasonable person test in like circumstances; employer communications; and previous warnings.

4.3 Discipline as part of administrative responses to individual behaviour

The government disposes of a series of possible responses to individual behaviour, of which disciplinary action is only one. The course of action taken by departments is dependent on how the conduct is characterized, either as culpable misconduct or as incompetence.

The Government of Canada's disciplinary and administrative frameworks that exist today are sound and compare with those of other comparable Westminster‑based jurisdictions. The range of sanctions and responses offered to managers is appropriate. The approaches adopted in the Public Service to date provide a good fundamental basis for the direct exercise of disciplinary authority by deputy heads conferred by the Public Service Modernization Act. Appendix B sets out an outline comparing the federal government's disciplinary and non-disciplinary authorities with those of provincial jurisdictions and some Commonwealth countries. The basic approach does differ. Some jurisdictions have one comprehensive piece of legislation providing a hierarchy of rules and systems governing the responsibilities of public service employees. Some impose specific duties on executives or provide for independent review of their performance. There is very little difference, however, in the types of sanctions available to discipline misconduct or mismanagement.

The onus to use the regime and to do so judiciously is placed directly on the management cadre in departments and agencies. This is especially so since the coming into force on April 1, 2005, of the Public Service Labour Relations Act. Treasury Board guidelines had already placed the responsibility on managers to develop, maintain, and amend codes of discipline that reflect departmental organization and mandate. While most organizations, especially large ones, do have codes, they do not at present specifically target behaviours that may lead to mismanagement. The special obligations of public service employees were referred to earlier. These are not well integrated into the disciplinary process and thinking. A consensus needs to be built within the staff relations community and the management community in two key areas: the impact of the failure to follow management rules and what then constitutes misconduct subject to discipline.

Public sector managers operate in a complex environment. For example, a case study involving possible discipline for mismanagement identified 25 Treasury Board policies that may come into play, most of them not overtly linked with each other or cross-referenced in any way. Not surprisingly, knowledge and awareness of the policies and procedures is often insufficient or low. This is taken into account in the renewal of the Treasury Board policy suite.

Finally, there are some cases where mismanagement is more appropriately characterized as non‑culpable—but poor—performance rather than as a disciplinary issue. There are reports that the abundance of redress mechanisms makes it difficult to address problems of poor performers.

In those situations, dealing with poor managers and poor performers becomes part of an appropriate response. The Public Service Modernization Act contains provisions that give some deference to a deputy head's opinion that an employees' performance is unsatisfactory when a decision to terminate or demote a poor performer is reviewed by an adjudicator.

The process that must be followed to respond to instances of non-culpable behaviour is not inordinately complex but requires a sustained effort. The available support of trained human resources specialists is probably the most important element in helping public service managers apply this process. Provisions of the Public Service Modernization Act also require that each deputy head implement informal conflict resolution mechanisms in his or her institution. This will provide a facilitating mechanism to deal with poor performance.

4.4 A look at disciplinary sanctions and administrative responses for specific groups of public service employees

The review also looked at accountability and sanction mechanisms applicable to members of the executive category, former employees, public office holders, and employees of Crown corporations. The purpose was to assess their appropriateness.

Executive group

As part of the public service senior cadre, members of the Executive group (EX) play a pivotal role in the establishment and maintenance of a culture that both frowns upon mismanagement and seeks to promote sound stewardship of government resources. Because of the leadership role they are expected to play and because they are also among the most mobile of public service employees, their collective attitudes, values, and conduct can greatly influence the entire Public Service. While the accountability of executives lies within the hierarchical structure of their own departments, a number of processes to collectively develop and manage the community are in place, particularly in the EX-04 and EX-05 (assistant deputy minister) ranks.

Some of the basic elements of good governance definitely include establishing clear accountabilities for senior members of the executive cadre as well as the mechanisms to hold them accountable. Certain jurisdictions have addressed some of these points in a very direct way. In some places, this has included specific provision dealing with the discipline of executives or the management of their performance. Some also provide for the discipline of executives by a party outside the executive's department.

In the Canadian public service, discipline of executives is frequently informal in nature, not formal. The concept of progressive discipline arose out of collective bargaining and is normally found in collective agreements. It lacks recognition in the common law context. Under common law, employees pass from warnings to termination for cause. As a result, the progressive discipline approach is not one that is necessarily expected to be applied in the same fashion, if at all, for members of management. In fact, just as the appropriate notice of termination period is calculated differently for executives and unionized employees, so too is the disciplinary approach. Indeed, a review of decisions reveals that conduct for which a unionized employee will be suspended may well constitute cause for termination of an executive.

As role models for the organization, executives are held to a higher standard. For career mobility, indeed for continued employment, a misconduct-free record is imperative. A relationship of trust is essential between senior management and departmental executives. The relatively few reported instances of misconduct or other difficulties speak to the culture of the relationship between executives and their supervisors and lead to informal sanctions involving executives being moved to another position. Since the remuneration of executives includes performance pay, those who have faced these difficulties in their management functions will see this reflected in the withholding of such pay. While formal disciplinary measures are usually eschewed, this is therefore most often in favour of a different, less formal approach, often involving a resignation.

This approach has the advantage of flexibility but leads to difficulties in ensuring a coherent approach to acts of mismanagement in the Public Service. It has also created the perception that executives are not held accountable, particularly for acts of mismanagement that occurred "on their watch." Since mismanagement in general is not necessarily detected or systematically sanctioned, this may contribute to a perception that the government has been lax in dealing with these types of situations. At the same time, there are factors and circumstances that are unique to executives that must be considered when determining disciplinary responses. This is reflected in the distinct policies and approaches that have been adopted to deal with situations where the employment of executives is terminated, including, for example, the Policy on Deployment of Executives that provides that executives at the higher levels may be transferred from one position to another without their consent and as operational needs arise.

An effective compliance framework requires the government to formalize possible responses to acts of executive mismanagement. This should still allow for flexibility and for approaches unique to the executive category. Given that mismanagement does not necessarily come to light immediately, mechanisms that would enable executives to be called to account for transgressions even though some time may have passed or they have moved to another position may sometimes be called for.

The principles outlined here should hold to the top-most level of any department. The government's desire to reward good executive management is to be communicated through action and recognition. It is as important as the responses to instances of mismanagement.

It is not realistic to assume that those who are evaluating executives are always better managers themselves. The government's approach to the Performance Management Program must recognize this and give executives the necessary tools to effectively manage their subordinates. Some departments have done a lot to bring the Performance Management Program to life and to ensure that managers get the full benefits from it.

Executives, like other groups of public service employees involved in the management of public resources, may have suffered from the absence of programs providing solid training in core management functions (although some have benefited from the executive development programs). While the government's human resources planning initiatives have established the validity of developing the senior management category, primary focus has been on the "softer" leadership capacities. These skills are intrinsic to good management; however, the practice may have slowed investment in the development of complementary elements, such as knowledge and understanding of the principles and management rules by which executives must govern themselves in performing their duties.

The government's renewed emphasis on good management has manifested itself notably through the development of the MAF. The MAF will encourage a more systematic consideration of management capabilities and performance as part of the evaluation of executives. The Leadership Network and the Public Service Commission of Canada are completing their work in developing a new competency profile for executives. Management excellence is one of four key leadership competencies, also including values and ethics that will be used in recruiting, assessing, and promoting executives in the Public Service. The leadership profile will also cover deputy ministers, heads of agencies, and managers in levels feeding the Executive group, facilitating the establishment of shared practices and values and the renewed culture in management.

Former public service employees

In a number of cases examined by the Auditor General of Canada, public service employees who appeared to have been implicated in acts of mismanagement were no longer employed by the time the reports were completed. This has prompted the consideration of the situation of former public service employees who may have committed acts of mismanagement while in office.

In the context of this review, these situations raised two issues:

- the impact of the employees' departure on the investigation; and

- the nature and relevance of the sanctions that may be imposed on these employees.

The reasons underlying these departures are not necessarily available. Some may have taken place as the result of a disciplinary process that culminated in an agreement to resign. Some public service employees may also have offered a resignation, unprompted, while an investigation was in progress.

Since the primary purpose of discipline is corrective, the imposition of a disciplinary action to a departing employee is unlikely to have the desired result. Furthermore, if the employee has already left, the employment relationship upon which rests the authority to impose disciplinary or administrative sanctions no longer exists.

At present, the government has some instruments at its disposal. Offences under the Criminal Code and the FAA do not make any distinctions based on the current employment status of the individual, and actual policies do require the disclosure of potential offences to the proper law enforcement agency. At the same time, monies owed by retired individuals can be set off from amounts owed to or by the Crown, including pension benefits. In fact, many departments and agencies will now withhold payment of termination benefits pending determination of outstanding claims where there is a risk that monies may be owed to the Crown.

The relative ease with which departments can contract directly or indirectly to obtain the services of public service employees raises an issue related to whether it is appropriate to retain the services of a person who was dismissed from the Public Service on grounds of mismanagement, short of having been found guilty of corruption. The same issue arises out of re-employment or employment by another public service employer or an agent Crown corporation. There is no general rule preventing a fired employee or an employee who resigns as part of the disciplinary process from being re-employed.

Public office holders

The review also looked at the situation of public office holders, principally Governor‑in‑Council appointees. At the time of writing, about 3,000 appointees held office, approximately 600 of whom were engaged on a full-time basis. From time to time, questions arise as to whether these appointees are obliged to comply with rules and are subject to the usual sanctions and enforcement regimes.

Governor‑in‑Council appointees are found in a variety of positions and organizations. They are appointed as heads and members of departments, agencies, boards, commissions, and Crown corporations. They include deputy ministers and deputy heads. For many of those, the MAF will stand as a statement of expectations.

The Privy Council Office has issued two documents to assist deputy ministers and heads of agencies: Guidance for Deputy Ministers[6] and A Guide Book for Heads of Agencies: Operations, Structures and Responsibilities in the Federal Government.[7] These publications help to define responsibilities and accountabilities, which translate into expectations. Taken together with the 2003 Values and Ethics Code for the Public Service, the Conflict of Interest and Post‑Employment Code for Public Office Holders issued in 2004, and the MAF, it is apparent that there is a substantive body of written work to assist the majority of public office holders in understanding the culture and values of the government, as well as performance expectations. The existence of this body of written work is not enough in and of itself.

There is evidence to suggest that some of the situations of mismanagement related to public office holders arise not because of deliberate malfeasance but because of misunderstandings of the rules, culture, or values related to public administration.

Two factors seem to influence these occurrences. First, many of these organizations have mandates that require them to perform quasi-judicial functions or otherwise carry out their activities in a manner that is more independent from the executive branch of the government than departments. At times, this independence with respect to mandate may be misinterpreted as independence in administration (financial and human resources management). In some instances, it appears that some public office holders experience difficulties in balancing the independence of their mandate with the defined set of government administrative requirements and values.

The fact that an organization has a mandate with a level of independence from the executive does not automatically translate into that same level of independence for the administration or management of the organization. There are a variety of examples of organizations that are independent in terms of how they carry out their mandate (for example, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada) but are still subject to the rubric of legislation, regulation, and policy that applies to financial management and the general administration of organizations that are scheduled under the FAA, whether those organizations are departments or tribunals.

The second factor is related to the first but occurs in organizations regardless of their level of independence. Some public office holders whose appointments are their first work experience with the federal government may bring with them a different set of cultural values. In some cases, they have not been successfully supported in developing the culture and instincts to adapt those practices to the public service environment. It is often the case that those different sets of values are nothing more than a manifestation of the difference between the rules in each environment. The majority of public office holders charged with management responsibilities are seen by observers as skilled and performing their jobs with integrity and competence. On some occasions, problems have occurred when public office holders appointed from outside of the Public Service legitimately believing that their non–Public Service experience was a factor leading to their appointment have not adapted past practices to their new public sector environment. Accordingly, they may have believed that managing in accordance with a set of cultural values and ethics garnered through their experience outside of government was both legitimate—and actually expected—by those responsible for their appointment. Occasionally, this approach has led to problems. Further measures could be developed to ensure that all appointees understand the differences in expectations, rules, and values within the public service environment.

Training and orientation programs, including orientation to public service culture and ethics, have been developed by the Secretariat, the Privy Council Office, and the Canada School of Public Service. These courses and programs provide public office holders with a sense of the public service culture and of the legislative and policy frameworks that govern their work. The learning mechanisms also serve to introduce new appointees to appropriate professional networks. At present, the public office holder determines whether he or she wishes to participate. In addition, the School is establishing the Senior Leaders Program with a curriculum focussed on core management accountabilities (finance, human resources, values and ethics, etc.).

Public office holders in Crown corporations

The directors of Crown corporations are usually part-time appointees and subject to the first part of the Conflict of Interest and Post-Employment Code for Public Office Holders (the Code). Chief executive officers (CEOs) are usually the only full-time public office holders and, as such, are subject to all parts of the Code. For Crown corporations, the Code represents a written set of expectations around the values and principles influencing the decisions of the CEO and directors. Boards of directors adopt, through bylaws, codes of conduct and procedures for the declaration and management of conflicts of interest. These tend to be designed to meet the particular characteristics of a particular corporation but are based on similar principles.

The Privy Council Office, working with the Secretariat, has developed a course on corporate governance (including a component on the Code of Values and Ethics for the Public Service) for any chair, CEO, or director appointed to a Crown corporation. The course describes the principles of corporate governance and the roles and responsibilities of the director.

Employees of Crown corporations

Assessing the processes available to sanction mismanagement by employees of Crown corporations was considered. As outlined in the Review of the Governance Framework for Canada's Crown Corporations, these corporations manage their day-to-day operations autonomously. Neither the Treasury Board nor any other part of the executive would play an investigative or enforcement role in relation to the conduct of employees of Crown corporations.

The findings of the Review of the Governance Framework for Canada's Crown Corporations do not require that these conclusions be revisited. It would not be appropriate to expand the role that the government can play with respect to the discipline of employees of Crown corporations.

The government does have oversight mechanisms in place with respect to Crown corporations themselves. All Crown corporations are required to carry out annual audits. Currently, 41 of 46 parent Crown corporations are audited by the Auditor General of Canada. The majority are subject to a special examination (a type of performance audit). In the Review of the Governance Framework for Canada's Crown Corporations, the government committed to giving the Auditor General of Canada the discretion to audit all Crown corporations (except for the Bank of Canada and the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board) as well as to requiring all Crown corporations to undergo special examinations by the Auditor General of Canada. The Budget Implementation Act, 2005, tabled by the government in the House of Commons on February 23, 2005, delivers on this commitment.

The Treasury Board and the government would still benefit from having means to satisfy themselves that Crowns and their employees do comply with the relevant provision of the FAA and related policies. This would require that the relevant information be made available to the Treasury Board as part of regular reporting.

5. Criminal Sanctions

The FAA sets out criminal offences for office holders having engaged in certain behaviours connected with the collection or management of public funds.

Research on compliance has confirmed that criminal proceedings are not necessarily the most appropriate—or most useful—first response to instances of mismanagement. In addition to its shortcomings as a deterrent and a tool to modify behaviours, the use of the criminal justice system is costly and slow, and the intervention of many different factors makes the outcome somewhat unpredictable. That said, there are certainly situations where the laying of criminal charges by law enforcement officers stands as a clearly appropriate response.

5.1 The current criminal regime

Corrupt and inefficient practices, described as rampant within federal government departments from the mid-1800s, are likely what led to Parliament's 1867 decision to set out the criminal liability of certain officers for the custody and accounting of public funds in sections of the Revenue Act. The essence of these provisions was retained in successive consolidated revenue acts—including the Consolidated Revenue and Audit Act of 1931—that centralized the financial mechanisms for government spending, thereby allowing for greater executive control.[8]

Criminal offences are set out in sections 80 and 81 of the FAA. For the most part, they pertain to corruption of public officials and falsification of records. Section 80 contains one specific offence that is committed when a person who manages funds for the government fails to report to a superior officer, in writing, information about a contravention of the FAA or its regulations.

Despite the long-standing existence of these provisions, a review of reports of judicial decisions rendered in Canada has failed to yield any judgment indicating that they have been used in prosecuting actual or former officials. The Attorney General's Federal Prosecution Service also advises that it has never been referred any charges for prosecution under the FAA by law enforcement officers.

This is not to say that actual or former employees have not been prosecuted. In fact, over the last two years, as reported in the media, there have been a number of occasions involving the laying of criminal charges related to employees' actions in the management of public funds. These charges were laid pursuant to provisions of the Criminal Code.[9]

Generally, the authority to prosecute offences under the Criminal Code is given to provincial attorneys general. Provincial Crown prosecutors work closely with law enforcement agencies operating in the same jurisdiction and will develop ongoing working relationships with police officers. Those working relationships, along with the familiarity of provincial prosecutors and police officers with the Criminal Code and its workings, are factors in establishing the preference to work with the Criminal Code rather than with the FAA (these prosecutions would normally be handled by federal Crown attorneys).

Under the Policy on Losses of Money and Offences and Other Illegal Acts Against the Crown, all losses of money and suspected cases of fraud, defalcation, or any other offence or illegal act against the Crown must be reported to law enforcement authorities. Police forces normally use a prioritization system to allocate resources to the investigation of a file or a category of files. From our consultations, it appears that these systems do not result in a very high priority being given to files involving breaches of the FAA, except where they may disclose instances of corruption or represent important occurrences of theft or fraud.

The law enforcement officials consulted during the review expressed the opinion that the provisions of the Criminal Code do not leave any gap and are broad enough to allow prosecution in the situations of serious mismanagement that they have encountered. Prosecutors and police officers also expressed a strong preference for working with the Criminal Code, with which they are familiar, rather than with a financial administration statute.

Criminal offences contravene fundamental rules and involve clearly apparent harm.[10] It is evident that the Criminal Code is a very comprehensive and useful tool for addressing clearly criminal activities.

A comparison between the offences contained in the FAA and those set out in the Criminal Code confirms that all of the FAA offences, save one, are found in both statutes. The exception is the failure to report a breach, which was referred to above, for which there is no counterpart in the Criminal Code.

This raises three possible scenarios: creating offences targeting specifically the responsibilities attributed to public service managers; simply doing away with offences in the FAA, recognizing that they are not used; or creating a regulatory regime in lieu of a criminal regime for FAA‑related offences.

5.2 Examining new directions

The scope of the FAA offences is very narrow. The types of conduct the FAA prohibits do not, for the most part, reflect the range of management duties and obligations. Section 126 of the Criminal Code, a provision that creates an offence for disobeying any federal statute, does fill this vacuum in part. This section is not very useful, however, in securing compliance with those particular provisions nor does it cover the breach of regulations.

The FAA sets out a number of positive obligations and duties, the breach of which could conceivably give rise to offences as follows:

- subsection 9(1): Failure to keep accounts in prescribed form

- subsections 9(2) and (3): Failure to provide information and any documents required by the Treasury Board

- subsection 17(1): Failure to deposit public money as required

- subsection 31(3): Failure to ensure an adequate system of internal control and audit

- sections 26 and 28: Making payments out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund, except as authorized

- subsections 24.1(1), (2), and 25(2): Forgiveness of debts or obligations in a way other than as provided

- section 160: Breaching regulations, prescribed policies, and procedures

Figure 3 illustrates the offences that Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa have included in their government financial administration legislation and that pertain specifically to duties and obligations created by those statutes. They vary greatly, and the penalties imposed by these jurisdictions also range from the very mild to the very harsh. For example, New Zealand stipulates a maximum $2,000 fine on a summary conviction for anyone refusing or failing to produce information in his or her possession or control relating to financial or banking activities of any Crown asset or liability. For the equivalent offence, South Africa imposes a maximum of 15 years' imprisonment upon conviction. Canada has the equivalent prohibition in the FAA but does not specifically provide for an offence in the event of a lack of compliance.[11]

Figure 3. Overview of Offences in Three Jurisdictions

Note: The UK does not have a general financial management statute.

| Description of Offence | Australia[12] | New Zealand[13] | South Africa[14] |

| Public money paid into a non-official account | √ | √ | √ |

| Receipt of public money by outsiders without the minister's authority | √ | ||

| Withdrawals from official accounts made without being authorized by the finance minister | √ | ||

| Misapplying or improperly disposing of or using public money | √ | ||

| Refusing or failing to provide information | √ | √ | |

| Resisting or obstructing persons acting in the discharge of their duties | √ | √ | |

| Making false statements or giving information knowing it to be false or misleading | √ | ||

| Committing acts for the purpose of procuring any improper payment of public money or improper use of any public financial resource | √ | ||

| Failure to keep records | √ | ||

| Destroying or tampering with records | √ | ||

| Failure to report suspicious or unusual transactions | √ | ||

| Unauthorized disclosure | √ | ||

| Misuse of information | √ | ||

| Failure to formulate and implement internal rules | √ | ||

| Failure to provide training or appoint a compliance officer | √ | ||

| Unauthorized access to or modification of the contents of a computer system | √ |

Canada's system of criminal offences for mismanagement has been operating under a duplicated regime. It is not clear that this duplication serves any purpose:

- First, the systematic preference for the Criminal Code may have affected the deterrence value of the existing FAA offences.

- Second, short of creating, funding, and promoting a special investigative and prosecuting capacity with a specific mandate, the federal government does not have any influence over how the law enforcement community approaches breaches of the FAA.[15]

This leaves the government with limited tools to address serious—though not criminal in the traditional sense of the term—instances of failure to abide by management rules. It raises a question as to whether a criminal regime that only minimally takes into account the specific nature of the FAA remains an appropriate tool.

The discussion above also raises the question of whether it is appropriate to have two sets of offences that practically duplicate each other. Removing the criminal sanctions would recognize that a threat of stiffer punishment does not bring about behaviour change and is not always appropriate in all situations. If accompanied by new administrative or regulatory sanctions, it also creates distinctions between fundamentally criminal behaviour and immoral behaviour that is not criminal at root. Law enforcement officers are more familiar with the Criminal Code and can efficiently work with this regime.

6.

Recovering Lost Funds

The FAA sets out criminal offences for office holders having engaged in certain behaviours connected with the collection or management of public funds.

The review examined tools and mechanisms available for debt recovery in the federal government. Consultations took place with senior financial officers, with government lawyers involved in debt collections, with the Office of the Comptroller General, and with Me. André Gauthier, appointed as special counsel for civil recoveries upon release of the November 2003 report of the Auditor General of Canada. Comments were also received from the community of financial officers.

6.1 The government's approach to debt recovery

The Canadian system of parliamentary democracy requires that the government account to Parliament for its handling of the funds entrusted to it. As part of its stewardship of public funds, the government of the day is also responsible to citizens for how it manages public monies.

The foundations for financial administration in Canada were established at the time of Confederation when broad principles were set, including a single consolidated fund for receipts and disbursements (the Consolidated Revenue Fund); parliamentary authority for the approval of taxes, expenditures, and borrowing; internal control systems for the safeguarding of public assets; and standard accounting and reporting.

These principles remain in effect today, and they have been strengthened through ongoing reform initiatives, such as the enactment of the FAA in 1951, the decentralization of financial administration responsibilities, and the creation of a financial administration policy promulgating mandatory requirements for all departments.