ARCHIVED - Mid-Term Evaluation of the Implementation of the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation

This page has been archived.

This page has been archived.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Mid-Term Evaluation of the Implementation of the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation

Final

Approved by Secretary May 5, 2011

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Issues and Methodology

- 3. Conclusions and Supporting Findings

- 3.1 Relevance

- 3.1.1 Do the Objectives of the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation Align With Federal Government Priorities and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's Strategic Outcome?

- 3.1.2 Is There a Continued Need for the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation? Do the Principles of the CDSR Respond to the Identified Need for Improvement in Regulations?

- 3.2 Effectiveness

- 3.2.1 Is the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation on Track Toward Achieving All of Its Intended Outputs? (capacity to implement the CDSR)

- 3.2.2 To What Extent Are the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's Regulatory Affairs Sector and Departments and Agencies Satisfied With the Outputs Produced? Are the Outputs Produced by TBS-RAS Responding to the Capacity Needs of Departments and Agencies?

- 3.2.3 Has the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's Regulatory Affairs Sector Experienced Any Barriers to Producing the Desired Level of Outputs?

- 3.2.4 To What Extent Is the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's Regulatory Affairs Sector on Track Toward Achieving Expected Outcomes Within the Next Two and a Half Years? To What Extent Has There Been an Increase in Capacity by Departments and Agencies to Meet CDSR Requirements?

- 3.2.5 Were There Any Unintended Impacts of the Implementation of the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation?

- 3.2.6 What Barriers Exist to Being Able to Measure a Change in the Intermediate Outcomes Within the Next Two and a Half Years?

- 3.3 Efficiency and Economy

- 3.3.1 Is the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation Being Delivered Efficiently and Economically to Produce Desired Outputs and Outcomes?

- 3.3.2 Are There Any Alternative Design and Delivery Approaches That Should Be Considered for the Implementation of the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation? Is the Centralized Approach, With Some Cost-Sharing Funds for Departments and Agencies, an Efficient Model?

- 3.1 Relevance

- 4. Summary and Recommendations

Executive Summary

This report presents the findings of the mid-term evaluation of the implementation of the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation (CDSR). The evaluation examines early implementation and progress toward immediate outcomes for the two-and-a-half-year period from the coming into force of the CDSR in April 2007 to fall 2009. As such, the scope is limited to Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat activities. The audience for this report is primarily senior management of the Secretariat.

Background to the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation

The External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation was created in 2003 to provide the Government of Canada with external perspective and expert advice on how to redesign Canada's regulatory approach for the twenty-first century. On April 1, 2007, in response to the Committee's recommendations, the CDSR was brought into force, replacing the Government of Canada Regulatory Policy(1999).

The CDSR introduced several key improvements, including a more comprehensive management approach with specific requirements for the development, implementation, evaluation and review of regulations. This new approach was intended to support the government's commitment to protect and advance the public interest in health, safety and security, the quality of the environment, and the social and economic well-being of Canadians through a more effective, efficient and accountable regulatory system.

Conclusions

Relevance

In establishing the External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation, and by implementing the CDSR to respond to its recommendations, the Government of Canada recognized the importance of regulations to the social and economic well-being of Canadians. The objectives of the CDSR continue to be aligned with federal government priorities and to address an identified need. These government regulatory priorities are identified in documents such as Budget Speeches, which call for regulatory approaches in specific areas, and are focused on achieving their intended objectives efficiently.

Performance—Effectiveness

A moderate level of success has been achieved to date. With a few exceptions (notably service standards), outputs such as training courses, advice, and tools to support departments and agencies have been produced as planned. The need for improvements in the areas of partnerships and communications has been identified. In addition, there has been a moderate increase in the capacity of departments and agencies to meet CDSR requirements in the areas of interdepartmental and interjurisdictional cooperation, reduction of administrative burden, use of service standards, cost-benefit analysis, and performance measurement and evaluation. This increased capacity has resulted in levels of compliance with CDSR requirements of over 90% in most of these areas.

The level of success achieved to date is the result of the collaboration between the Regulatory Affairs Sector of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS-RAS) and departments and agencies. Making further progress on desired outcomes within the next two and a half years, including intermediate outcomes felt by regulated industries, will depend on whether departments and TBS-RAS can recruit and retain qualified personnel with the appropriate skills set or can access this expertise when needed, and on whether TBS-RAS has the required resources. A significant barrier to evaluating the extent to which these intermediate outcomes are achieved is the lack of performance measurement information. Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plans are required for high-impact regulations only, and this just since July 2009.

Performance—Efficiency and Economy

TBS-RAS was able to achieve the outputs and outcomes described above with limited resources and at a lower cost than originally expected, thus demonstrating both efficiency and economy. The current model, in which TBS-RAS acts as a central oversight body, is consistent with best practices of countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. No alternatives were identified.

Recommendations

The recommendations for TBS-RAS can be grouped into three main areas:

- Ensuring that departments and agencies have adequate support going forward

- Increasing and improving communications

- Ensuring that reporting requirements are met

Support for Departments and Agencies

Despite limited resources, TBS-RAS has developed products that have allowed departments and agencies to increase their capacity to meet CDSR requirements. Additional increases in capacity can be achieved with more targeted support.

Recommendation 1: Address the remaining gaps in outputs, such as guidance on service standards.

Recommendation 2: Continue the current efforts to create pools of qualified cost-benefit analysts and regulatory experts to help ensure that departments and agencies have access to individuals with the appropriate skills set.

Communications

Products and services can help achieve increases in capacity only if they are known and used. TBS-RAS needs to focus on communicating more effectively with departments and agencies, as a number of them were unfamiliar with its products and services.

Recommendation 3:Establish an overall communications strategy for the CDSR. In particular, departments and agencies need to be made aware of TBS-RAS products and services, partnering efforts, and research and information-sharing initiatives.

Reporting

Reporting on production of outputs, use of financial resources, and achievement of outcomes is important for identifying:

- progress made with resources used, for accountability purposes; and

- gaps in performance, in order to guide future plans.

Improvements are required so that reporting can be used as intended. Specifically, there are gaps in reporting, both on the use of funds allocated for CDSR implementation and on leveraged resources. In addition, departments and agencies need feedback from TBS-RAS on their progress in implementing the CDSR.

Recommendation 4: Ensure that reporting requirements are met and that departments and agencies include the level of additional resources (if any) expended to meet CDSR requirements. Full reporting will provide a government-wide picture of CDSR resource needs.

Recommendation 5: Complete departments' performance reports and communicate the results to ensure that departments and agencies receive the feedback needed.

Recommendation 6: Begin planning for the five-year evaluation within the next six months to ensure that a performance measurement strategy is in place and that appropriate data are captured in an ongoing, systematic and user-friendly manner.

Management-Led Review of the Centre of Regulatory Expertise

TBS-RAS conducted a concurrent management-led review that focused on early impacts of the Centre of Regulatory Expertise. The Centre is one of three divisions within TBS-RAS and was established in October 2007 to help federal regulatory organizations build their internal capacity to comply with the CDSR. The management-led review consisted of case studies, a document review, interviews with internal and external stakeholders, and a survey of users of the Centre's services.

The review demonstrated that the Centre of Regulatory Expertise has developed into a fully functional unit with established workplace structures and processes. Overwhelmingly, users of the Centre's services expressed satisfaction with both the quality of the assistance and the enabling approach to delivery of assistance. The review concluded that the Centre has been successful in supporting the other TBS-RAS divisions and in increasing capacity in regulatory organizations. The review also identified some key barriers, outside the Centre's control, to continued success, notably acute turnover within regulatory organizations and a lack of senior management engagement in regulatory organizations. The Centre has produced a large number of outputs that are generally considered to be high-quality, including key areas of regulatory learning and networking.

Overall, this review provides useful information in light of the evaluation of the implementation of the CDSR. In particular, the review identified a need to leverage the early successes achieved by the Centre of Regulatory Expertise through a coherent communications strategy that clearly distinguishes the role of Centre and the role of Policy and Operations divisions in relation to regulatory departments. It also suggests that the Centre revisit its measures concerning the concept of building capacity. Evidence gathered for the review also led to the recommendation that the Centre's funding should continue past its current sunset date of 2012.

1. Introduction

This report presents the findings of the mid-term evaluation of the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation (CDSR), a policy managed by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's Regulatory Affairs Sector (TBS-RAS). The evaluation was conducted by Government Consulting Services of Public Works and Government Services Canada, and covers the two-and-a-half-year period from the implementation of the CDSR in April 2007 to fall 2009.

This evaluation was a Treasury Board commitment and examines early implementation and progress toward immediate outcomes. As such, the scope is limited to Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat activities. The audience for this report is primarily senior management of the Secretariat.

To meet the requirements of the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation, the Secretariat's Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau provided a stewardship role for the conduct of this evaluation. In addition, the Secretariat's Departmental Evaluation Committee reviewed this report and recommended it for approval by the Secretary of the Treasury Board.

The evaluation report is organized as follows:

- Section 1 provides an introduction to the CDSR and its implementation.

- Section 2 describes the evaluation issues and the methodology of the evaluation.

- Section 3 presents conclusions and supporting findings for each evaluation issue and question.

- Section 4 presents a summary and recommendations.

1.1 Background to the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation

The External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation was established in 2003 to provide the Government of Canada with external perspective and expert advice on how to redesign its regulatory approach for the twenty-first century.

The establishment of the Committee underscored the importance of regulation as a key mechanism to protect the social and economic well-being of Canadians and Canada's environment, as well as its impact on Canadian citizens and industries. It also recognized that Canada's regulatory approach needed to be reviewed in light of:

- the speed of modern society, with its global flow of commerce, instant access to information, rapid innovation to meet changing consumer needs, and greater competitiveness;

- the increasing complexity of policies, including those that are cross-disciplinary (e.g., bioproducts) or in new areas (e.g., sustainable development); and

- the rising expectations of Canadians for greater accountability and transparency.

In its 2004 report, Smart Regulation: A Regulatory Strategy for Canada, the Committee noted that Canada had a sound regulatory foundation but that major shifts in perspective and practice were needed to respond to the trends described above. Its recommendations addressed the need for:

- increased regulatory cooperation at the international, federal, provincial and territorial levels and within the federal government itself;

- greater use of risk management in regulatory approaches;

- a framework to guide the mix of policy instruments and the associated compliance and enforcement strategies;

- the adoption of a regulatory process that is more effective, cost-efficient, timely, transparent, accountable, and focused on results; and

- an increase in government capacity relating to regulation.

The Committee also made a number of recommendations relating to specific industries and sectors.

The CDSR was the mechanism through which the government addressed a number of the Committee's recommendations. The CDSR, announced in Budget 2007 as a replacement for the Government of Canada Regulatory Policy(1999), was the product of two years of collaboration between the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and federal regulatory departments and agencies, as well as consultations with a wide cross-section of stakeholders, including environmental and consumer groups, industry and small business, and provinces and territories.

The changes introduced by the CDSR were intended to support a sound and effective regulatory system providing consistency, fairness and transparency and supporting innovation, productivity and competition. The most important changes were:

- a process to address the full regulatory life cycle, with specific requirements for the development, implementation, evaluation and review of regulations;

- better coordination across governments and jurisdictions to address overlap and duplication;

- enhanced guidance where gaps were identified (e.g., cost-benefit analysis and performance measurement) to enhance the transparency, quality, analytic rigour and utility of regulations for decision making;

- early assessment in order to focus resources on regulatory proposals having the highest impact; and

- service standards and reporting on results.

1.2 Overview of the Regulatory Affairs Sector

In 1998, the Regulatory Affairs and Orders in Council Secretariat was established in the Privy Council Office to provide increased coordination and support to ministers on regulatory matters. In 2006, it was transferred to the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, and renamed the Regulatory Affairs Sector.

TBS-RAS supports the Treasury Board Committee in its role as the Queen's Privy Council for Canada by providing advice to the Governor General, and management and oversight of the government's regulatory function. It also provides policy leadership on the CDSR, the federal regulatory policy. As such, TBS-RAS is engaged in two key functions: supporting government priorities through continuous improvement of the CDSR and advising Treasury Board Ministers on Governor-in-Council submissions.

The implementation of the CDSR was carried out jointly by TBS-RAS's three divisions:

- Policy Division provides leadershipwithin the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, federally, nationally and internationally, to implement the CDSR and to maintain the relevance and integrity of federal regulatory policy by:

- interpreting the CDSR and developing guidance to explain its requirements;

- co-chairing the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Committee on Regulatory Governance and Reform; and

- undertaking intelligence gathering and sharing best practices with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the United States, and the European Commission to improve regulatory analysis and management.

- Cabinet Committee Operations carries out a challenge and oversight function for Governor-in-Council regulations and Orders in Council, to provide the highest-quality analysis to support Treasury Board (Part B) decision making.

- Centre of Regulatory Expertise supports the regulatory community by engaging experts to assist departments directly with addressing gaps in their capacity to conduct cost-benefit analysis and risk assessment and to prepare Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plans and Regulatory Impact Analysis Statements. The Centre of Regulatory Expertise works with the Canada School of Public Service and the Community of Federal Regulators to design and deliver training.

The base budget for TBS-RAS is approximately $5 million and includes funds provided through the CDSR Treasury Board submission for the following[1]:

- Strengthening the central agency function ($9.9 million over five years)

- Establishing the Centre of Regulatory Expertise ($6.4 million over five years)

- Providing financial assistance ($2.26 million over two years) for departments and agencies to coordinate the implementation of the CDSR

1.3 Expected Outcomes of the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation

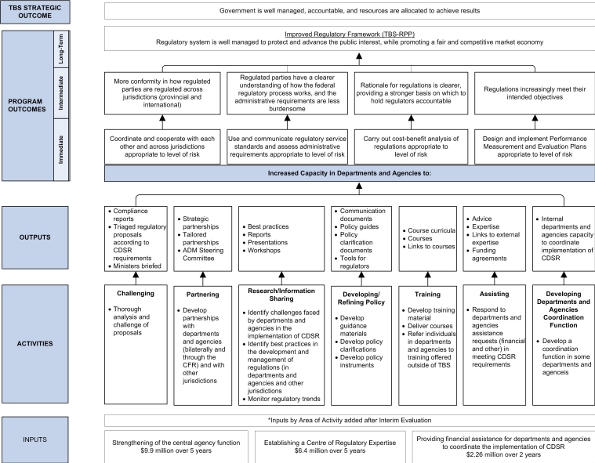

As illustrated in Figure 1, the immediate focus of the funding for departments and agencies is to

increase departmental capacity to meet the requirements of the CDSR. Departments and agencies, through a risk-based approach, should demonstrate an increased capacity to:

- coordinate and cooperate with each other and across jurisdictions;

- use and communicate regulatory service standards and assess administrative requirements;

- carry out cost-benefit analysis of regulations; and

- design and implement Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plans.

A risk-based approach means that analytical requirements for departments and agencies and the level of review conducted by TBS-RAS are commensurate with the impact of the proposal. For example, high-impact proposals require quantitative cost-benefit analysis, whereas low-impact proposals may require only a qualitative description of the costs and benefits.

Once organizations have the capacity to meet the requirements of the CDSR, the following outcomes are expected:

- Parties are regulated more consistently across jurisdictions (provincial and international).

- Regulated parties have a better understanding of the federal regulatory process and a reduced administrative burden.

- The rationale for regulations is clearer, providing a stronger basis for regulator accountability.

- Regulations increasingly meet the intended objectives.

In the long term, the regulatory system will be well managed to protect and advance the public interest while promoting a fair and competitive market economy.

Figure 1. Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation—Logic Model

2. Evaluation Issues and Methodology

This evaluation covers the period from the coming into force of the CDSR in April 2007 to fall 2009. It is a mid-term evaluation and therefore examines early implementation and progress toward immediate outcomes. The evaluation focuses on those Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat activities intended to achieve the immediate outcome of increasing the capacity of departments to conduct activities related to the CDSR.

2.1 Evaluation Issues and Questions

The questions for this evaluation focused on activities associated with the implementation of the CDSR and funded by the allocations described in par. 1.2, and were designed to measure how much progress had been made toward achieving the immediate outcomes. The research questions for the evaluation are listed below.[2]

Relevance

R1. Is there a continued need for the CDSR?

- Do the principles of the CDSR respond to the identified need for improvement in regulations?

R2. Do the objectives of the CDSR align with federal government priorities and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's strategic outcome?

Performance(Effectiveness)

P1. Is the CDSR on track toward achieving all of its intended outputs? (capacity to implement the CDSR)

P2. To what extent are TBS-RAS and departments and agencies satisfied with the outputs produced?

- Are the outputs produced by TBS-RAS responding to the capacity needs of departments and agencies?

P3. Has TBS-RAS experienced any barriers to producing the desired level of outputs?

P4. To what extent is TBS-RAS on track toward achieving expected outcomes within the next two and a half years?

- To what extent has there been an increase in capacity by departments and agencies to meet CDSR requirements?

P5. What barriers exist to being able to measure a change in the intermediate outcomes within the next two and a half years?

P6. Were there any unintended impacts of the implementation of the CDSR?

Performance(Efficiency and Economy)

P7. Is the CDSR being delivered efficiently and economically to produce desired outputs and outcomes?

P8. Are there any alternative design and delivery approaches that should be considered for the implementation of the CDSR?

- Is the centralized approach, with some cost-sharing funds for departments and agencies, an efficient model?

For each evaluation question, one or more indicators were developed, along with appropriate methods and sources of evidence. The relationships between the evaluation questions, the indicators, the methods, and the sources of evidence are shown in Appendix A.

2.2 Data Collection Methods

The CDSR Evaluation Matrix (Appendix A) uses multiple lines of evidence and complementary research methods, both quantitative and qualitative, to ensure the reliability of the information collected. Five main lines of evidence were used: document and literature review, interviews, a survey of departments and agencies, analysis of performance data from existing databases, and a review of financial data. Each data source is described below by line of evidence.

2.2.1 Document and Literature Review

The following types of policy, planning and reporting documents were reviewed and analyzed to assess continued relevance:

- Speech from the Throne, budgets, policies and legislation

- Mandate and program authority documents

- CDSR Treasury Board Submission

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's Management Resources and Results Structure and its Program Activity Architecture

- Reports and reviews:

- Departmental Performance Reports and other progress or performance reports

- Smart Regulation: A Regulatory Strategy for Canada

- OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform—Regulatory Reform in Canada—Government Capacity to Assure High Quality Regulation

- December 2000 Report of the Auditor General—Chapter 24: Appendix A—Government of Canada Regulatory Policy, November 1999

- Other documents, including opinions and perceptions of regulated parties on change

Both print and electronic documents were reviewed, using a customized template to extract relevant information from the documents and to organize it according to the indicators and evaluation questions in Appendix A. Appendix B provides a complete list of the documents reviewed.

2.2.2 Interviews

Interviews served as an important source of information for the evaluation, providing qualitative and quantitative input on relevance, results, and effectiveness of the CDSR implementation. Because not all stakeholders could be interviewed, the evaluation team selected a sample to ensure that appropriate interests and organizations were represented. A total of twelve interviews were conducted as part of the evaluation. The key informants were four TBS-RAS employees and eight representatives from departments and agencies, including three low, three medium and two heavy regulatory submitters.

All interviews were conducted in person. Interviewees were contacted to schedule an appropriate time and were sent an interview guide (Appendix C) in advance. The findings of the interviews were compiled and summarized by evaluation question and indicator.

2.2.3 Survey of Departments and Agencies

The evaluation team sent a Web-based survey to the TBS-RAS distribution list of 70 contacts[3] involved in the coordination of regulations for their departments and agencies. The survey was posted online for three weeks, and two reminder emails were sent during this period. Of the 70 contacts that were sent the survey, 34 responses were received, of which 30 were considered valid. The response rate is shown in Table 1.

| Survey Group | Total Sent | Received | Removed | Total Kepts | Response Rate | Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Departments and agencies | 70 | 34 | 4 | 30 | 42.9 % | 95% ± 13% |

Templates were populated with the survey responses to analyze the data according to the performance indicators and evaluation questions identified in the Evaluation Matrix. Because some organizations were over-represented among the respondents, the data were reweighted so as not to skew the results toward the experience of a few departments. Appendix D shows the weights that were applied. As a result, the analysis was conducted using a weighted population of 19 respondents. Furthermore, not all participants answered all survey questions. Where the variance is important, the number of non‑respondents has been noted in the report. The detailed survey results are provided in Appendix E.

TBS-RAS requested a second analysis where the survey responses were weighted to represent the volume of regulatory activities carried out by departments and agencies over the last two years. The assigned weights are shown in Appendix D. Analyzing the survey in this way highlights the findings of organizations having a high volume of regulatory activity.

2.2.4 Performance Data

Since a performance measurement system specific to the implementation of the CDSR did not exist, a data collection template was developed to capture data on outputs. Existing administrative data and performance data (e.g., client satisfaction surveys) were also reviewed to assess production of outputs and progress toward immediate outcomes. The performance data results were summarized by evaluation question and indicator.

2.2.5 Financial Data

Financial data were analyzed to determine the trend in planned versus actual resource use. TBS‑RAS also provided estimates of the allocation of resources to each of the activity areas in the CDSR logic model. The financial data, combined with the output and outcome findings, provided the basis for determining efficiency (i.e., outputs relative to resource use) and economy (i.e., outcomes relative to resource use). The financial data results were summarized by evaluation question and indicator.

2.3 Limitations of the Evaluation Methodology

2.3.1 Concurrent Studies

Other studies were being carried out concurrently in TBS-RAS, including the Performance Measurement and Evaluation Best Practices Study and the Management-led Review of the Centre of Regulatory Expertise (CORE). Because the implementation of the CDSR is highly dependent on the Centre's activities, TBS-RAS was aware of the potential for duplication and was committed to coordinating the various projects. To avoid interviewee and survey respondent fatigue, different interviewees and lists of survey candidates were identified for each of the studies, while still ensuring that these participants were representative of the population within departments and agencies involved in CDSR implementation.

2.3.2 Performance Measurement Information

Because there was minimal reporting in the early part of the pilot project, only limited data were available to address issues of efficiency and economy, or of leveraging (i.e., the contribution of resources made by departments and agencies relative to those provided through the CDSR). It was hoped that the survey would provide an estimate of the level of additional resources provided by departments and agencies to implement the CDSR, but survey respondents were unable to provide this information. It was therefore not possible to quantify the degree of leveraging achieved.

2.3.3 Survey Response Rate

Although the survey response rate (43%) was not as high as expected, the responses that were provided to the survey aligned well with those of the interviewees. Furthermore, the respondents were fairly representative of departments having low, medium and high regulatory activity.

2.3.4 Conclusion

Although the evaluation methodology does have some limitations, it was designed to use multiple lines of evidence to draw conclusions about the CDSR, thus strengthening the reliability and validity of the evaluation results. Notwithstanding the limitations, the methodology meets the requirements of the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation and associated standards.

3. Conclusions and Supporting Findings

3.1 Relevance

3.1.1 Do the Objectives of the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation Align With Federal Government Priorities and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's Strategic Outcome?

Conclusion: The objectives of the CDSR do align with federal government priorities of protecting and advancing the public interest and competitiveness through a more effective, efficient and accountable regulatory system. They also align with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's strategic outcome.

The CDSR objectives are to:

- protect and advance the public interest;

- promote a fair and competitive market economy;

- make decisions based on evidence;

- create accessible, understandable and responsive regulation;

- advance the efficiency and effectiveness of regulation; and

- require timeliness, policy coherence and minimal duplication.

The CDSR is the mechanism by which the government achieves its regulatory priorities. Since its implementation in April 2007, every Speech from the Throne and Budget Speech has included references to regulatory priorities that are not only consistent with CDSR objectives, but that are also expected to be more easily attained because of the CDSR. For example, the 2010 Speech from the Throne stated: “To support responsible development of Canada's energy and mineral resources, our Government will untangle the daunting maze of regulations that needlessly complicates project approvals, replacing it with simpler, clearer processes that offer improved environmental protection and greater certainty to industry.”

3.1.2 Is There a Continued Need for the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation? Do the Principles of the CDSR Respond to the Identified Need for Improvement in Regulations?

Conclusion: The CDSR responds to the needed improvements to Canada's regulatory approach identified by the External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation.

The Government of Canada amends or implements approximately 250 regulations a year. Of these, approximately 10% are considered high-impact: they may be highly controversial; they may represent a significant change to the status quo; or they may seriously affect such areas as health and safety, the environment, the economy or government. Given the number and complexity of regulations, a policy or framework is needed to guide the process of implementing regulations efficiently and effectively to support the well-being of Canadians. The CDSR supports the government's commitment to protect and advance the public interest by working with Canadians and other governments so that regulatory activities provide the greatest possible benefit to current and future generations of Canadians.

The External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation was created to provide the federal government with external perspective and expert advice on how to redesign its regulatory approach for the twenty-first century. Every major industrial sector told the Committee that the existing regulatory system often acted as a constraint to innovation, competitiveness, investment and trade. The Committee's report noted that if the regulatory “system is not aligned with new developments and practices of the twenty-first century, it may put Canadians' safety at risk and affect citizens' trust in government.” Furthermore, “other countries are reforming their systems, and Canada cannot afford to be left behind.”[4]The CDSR responds to both the recommendations of the Committee and the needs of the regulatory system.

3.2 Effectiveness

3.2.1 Is the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation on Track Toward Achieving All of Its Intended Outputs? (capacity to implement the CDSR)

Conclusion:The implementation of the CDSR is on track to produce most of its intended outputs. However, some gaps, such as the development of service standards, need to be addressed in the next two and a half years.

The administrative data show that the following outputs have been achieved:

- Training—Five regulatory courses have been developed, and each has been delivered on several occasions to federal regulators through the Canada School of Public Service.

- Partnership development—Strategic partnerships have been established with academic organizations, departmental and agency regulatory units, and other jurisdictions.

- Provision of advice and expertise through theCentre of Regulatory Expertise—Advice has been provided to federal departments and agencies on issues relating to cost-benefit analysis, performance measurement, and Regulatory Impact Analysis Statements.

- Research and information sharing—TBS-RAS has published reports and delivered presentations and workshops.

- Developing and refining policy—TBS-RAS has developed tools to assist regulators in areas such as cost-benefit analysis, risk assessment, and performance measurement and evaluation.

- Regulatory coordination functionshave been established in most departments.

The key gaps in output that TBS-RAS needs to address in the next two and a half years are (a) the development of service standards for regulations (as part of its policy development and refinement activities) and (b) linking departments and agencies to external experts (as part of its assistance to departments' activities). In addition, TBS-RAS compliance reports on the results of TBS-RAS challenge activities have been delayed.

Under the CDSR, “Departments and agencies are responsible for putting in place the processes to implement regulatory programs and to manage human and financial resources effectively, including publishing service standards, including timelines for approval processes set out in regulations, setting transparent program objectives, and identifying requirements for approval processes.” TBS-RAS had intended to provide guidance on service standards to assist organizations in complying with this requirement, but this guidance has been delayed to ensure consistency with the new Treasury Board Policy on Service Standards, which has yet to be finalized.

While somewhat delayed, TBS-RAS has started to link departments and agencies with external experts to enable them to meet CDSR requirements using Regulatory Cooperation Plans (RCPs) or specific procurement streams. RCPs are a funding mechanism that helps departments increase their capacity to meet CDSR requirements. At the time of the evaluation, RCPs were in place for seven departments having a high volume of regulations. However, they were not in place for other departments having low capacity in at least one of the CDSR requirement areas. In fact, a number of departments surveyed that had obtained funding under RCPs were unaware that they had received funding. This perceived lack of funding does not affect the progress toward outputs, but it suggests that more focused communications in this area by may be required.

TBS-RAS activities also include the analysis and challenge of departmental regulatory proposals. The output of this activity was meant to be compliance reports shared with the regulatory community and used to identify gaps that needed to be addressed. TBS-RAS is now focusing on producing these performance reports and has completed them for the first two quarters of fiscal year 2009–10. Plans have also been made to complete performance reports going back to 2004, which will allow for a comparison of regulatory proposals pre- and post-CDSR.

3.2.2 To What Extent Are the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's Regulatory Affairs Sector andDepartments and Agencies Satisfied With the Outputs Produced? Are the Outputs Produced by TBS-RAS Responding to the Capacity Needs of Departments and Agencies?

Conclusion: Generally, departments and agencies were quite satisfied with TBS-RAS products and services used, but less satisfied with the level of TBS-RAS communications and partnering. In addition, some departments and agencies are not aware of (or are not using) the full range of TBS-RAS outputs and services, including partnering, a finding that is consistent with insufficient levels of communication.

TBS-RAS staff reported that they were satisfied with the outputs produced. Some areas for improvement were identified, but there was no consistent theme. Just over 50% of departmental survey respondents reported that they were generally satisfied with the outputs produced by TBS-RAS, including Canada School of Public Service courses, advice on how to meet CDSR requirements, and analysis of proposals.[5]

However, at least 30% of survey respondents reported that they were not satisfied with efforts of TBS-RAS to foster partnerships or with the overall communications strategy for the implementation of the CDSR. In addition, just over 50% of survey respondents could not comment on some of the outputs produced by TBS-RAS (e.g., funding agreements or partnerships), suggesting a possible lack of awareness or use of these services. These survey findings (lower levels of satisfaction with partnerships and communications, and an inability to comment on some outputs) applied to departments and agencies having both low and high regulatory activity.

- When asked about the level of satisfaction with partnerships developed within government and with other jurisdictions, those survey respondents who provided a rating indicated that they were less satisfied with work done in this area, but many provided a response of “don't know.” The program data reveal that partnerships have been developed internationally, with provinces and territories, with universities, within the federal government, and with the Community of Federal Regulators, indicating that TBS-RAS's Policy and Centre of Regulatory Expertise divisions are active in developing partnerships. The apparent disconnect between the survey responses and the document review suggests that survey respondents who indicated a lower level of satisfaction may have done so because of a lack of knowledge about TBS-RAS efforts rather than because of dissatisfaction with partnering outputs. It should be noted that while survey responses of “don't know” were particularly high for questions relating to partnering, they were also as high as 50% for some other areas, suggesting a general lack of communication by TBS-RAS to departments and agencies about the specific services offered.

3.2.3 Has the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's Regulatory Affairs Sector Experienced Any Barriers to Producing the Desired Level of Outputs?

Conclusion: The most significant barrier to producing CDSR outputs, both in TBS-RAS and in departments and agencies, is the recruitment and retention of qualified personnel in specific areas of expertise (e.g., cost-benefit analysis and Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plans).

TBS-RAS has not identified any barriers to producing outputs, with the exception of finding and keeping qualified personnel. Some of the department interviewees did report that TBS-RAS did not have enough resources or experienced staff, especially given issues of employee turnover.

When interviewees were asked about the sustainability of the changes in departmental capacity to respond to the CDSR, 25% expressed concerns about employee turnover and recruitment. To help alleviate resource pressures, TBS-RAS and the Community of Federal Regulators have been working together to create a pool of qualified regulators who would be available to all departments and agencies to help address gaps in capacity.

3.2.4 To What Extent Is the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's Regulatory Affairs Sector on Track Toward Achieving Expected Outcomes Within the Next Two and a Half Years? To What Extent Has There Been an Increase in Capacity by Departments and Agencies to Meet CDSR Requirements?

Conclusion: TBS-RAS has completed a large part of the foundation work to bring about the change in expected outcomes within the next two and a half years. Departments and agencies have achieved increased capacity in all targeted areas―coordination and cooperation, regulatory service standards and assessment of administrative requirements, cost-benefit analysis, and Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plans.

The CDSR immediate outcomes are intended to increase the following capacities of departments and agencies to meet CDSR requirements, while tailoring effort to the level of risk associated with regulatory proposals:

- Capacity for departments and agencies to coordinate and cooperate with each other and across jurisdictions

- Capacity for departments and agencies to use and communicate regulatory service standards and to assess administrative requirements

- Capacity for departments and agencies to carry out cost-benefit analyses of regulations

- Capacity for departments and agencies to design and implement Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plans

Although it was not expected that CDSR outcomes would be fully achieved by the mid-term of the implementation period, the evidence shows that, overall, capacity in the above areas is increasing. Departmental self-assessments of capacity to meet CDSR requirements, and of compliance with those requirements, show that outcomes are beginning to be achieved.

Survey respondents were asked to retrospectively rate their capacity to deliver on immediate outcomes in April 2007, when the CDSR was introduced, and again in fall 2009. The results are shown in Table 2. The average capacity rating in 2007 was highest (an average of 3.45 out of 5) for coordination and cooperation, and organizations rated this capacity as only slightly (10%) higher in 2009. Organizations rated themselves as having achieved significant increases, ranging from 23% to 72%, in the other four capacity areas. Because of the moderate ratings for all five capacity areas, however, there continues to be opportunity for improvement. It should be noted that the capacity to design and implement Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plans for regulations was rated the lowest, with an average rating of 2.62. This low rating may be due to the relatively new requirements to develop Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plans for high-risk regulations, which were introduced only in July 2009. The greatest changes in capacity were identified in those areas where organizations initially rated the weakest, indicating that investment in these areas was well targeted.

| Capacity Rating | No Answer | Change in Rating | Increase (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 2007 | Fall 2009 | ||||

| a. Survey respondents rated their capacity using a five-point scale, where 1 was no capacity and 5 was fully capable. | |||||

| Coordinate and cooperate with other federal departments and agencies and across jurisdictions in the development of regulations | 3.45 | 3.80 | 6 | 0.35 | 10 |

| Assess the administrative requirements of regulations with a view to making them less burdensome | 2.94 | 3.63 | 6 | 0.69 | 23 |

| Use and communicate regulatory service standards | 2.75 | 3.49 | 9 | 0.74 | 26 |

| Carry out cost-benefit analysis of regulations | 2.33 | 3.04 | 4 | 0.71 | 37 |

| Design and implement Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plans for regulations | 1.52 | 2.62 | 5 | 1.10 | 72 |

In terms of support for capacity building, just over 50% of departments and agencies reported that the support provided by TBS-RAS was adequate. On average, organizations attributed nearly half of the change in their capacity to TBS-RAS. Perhaps not surprisingly, areas in which organizations rated their capacity as lowest also received the lowest ratings of satisfaction with TBS-RAS services.

One indicator of the capacity of departments and agencies to comply with CDSR requirements is the extent to which they do comply with those requirements. Although organizations rated their capacity in the mid-range, the performance reports for the first two quarters of 2009–10 actually show a high level of compliance (90%) with CDSR requirements. The only area below 90% is the capacity for cost-benefit analysis, which is still high, at 86% for the first quarter and 73% for the second quarter. Even with high compliance rates, respondents from departments and agencies for both the survey and interviews identified a need for more feedback from TBS-RAS on their organization's progress in meeting CDSR requirements.

3.2.5 Were There Any Unintended Impacts of the Implementation of the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation?

Conclusion: Unintended impacts reported by survey respondents include increased workload and time requirements combined with resource levels that have not kept up with the increased workload.

Among survey respondents who reported unintended impacts, approximately 25% saw increased workload and time requirements for the development of Regulatory Impact Analysis Statements and triage statements, as well as increased analysis requirements for high-impact regulations. A few respondents reported that their departmental regulatory function had not kept up with the increased requirements and that it lacked resources to meet the requirements.

3.2.6 What Barriers Exist to Being Able to Measure a Change in the Intermediate Outcomes Within the Next Two and a Half Years?

Conclusion: Potential barriers to measuring change in intermediate outcomes in the next two and a half years include inadequate time for changes to become apparent, insufficient resources and a lack of performance measurement information.

There was an expectation that intermediate outcomes (i.e., those that flow from the increased capacity already being demonstrated) could be measured in 2011, at the time of the five-year evaluation. These intermediate outcomes (Figure 1) are those expected to be felt by regulated industries.

Overall, the evaluation found limited feedback on barriers to measuring changes felt by industries in the next two and a half years. Among the interviewees who provided responses, the most common observations were that:

- regulated industries may not perceive any changes by 2011; and

- the current resource levels are inadequate to achieve the expected changes within this time frame.

Some of the intermediate outcomes can be partially measured by surveying the industries on their perceptions, such as whether the regulatory burden has decreased. However, the intermediate outcome of regulations increasingly meeting their intended objectives may be difficult to measure because of insufficient performance information.

In July 2009, the requirement to develop and implement Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plans for high-impact regulations was put in place. High-impact regulations produce 80% to 90% of the impacts resulting from regulations, but represent only about 10% of the regulations produced. Performance measurement and evaluation data for high-impact regulations alone would not provide adequate information about the overall outcomes achieved by regulations. The lack of a CDSR-specific performance measurement strategy is a barrier to a quality evaluation being conducted in 2011.

3.3 Efficiency and Economy

Efficiency generally means maximizing the outputs produced with a fixed level of inputs or minimizing the inputs used to produce a fixed level of outputs. Economy has a similar meaning, but with the intent to maximize expected outcomes, rather than outputs.

3.3.1 Is the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation Being Delivered Efficiently and Economically to Produce Desired Outputs and Outcomes?

Conclusion: The CDSR is demonstrating both efficiency and economy in producing the desired outputs and outcomes despite encountering funding restrictions and delays in funding. However, the degree of leveraging could not be determined, although it is implied given the sharing of tasks between TBS-RAS and departments and agencies.

Funds to begin the implementation of CDSR were expected in the spring of 2007–08, but were not received until October of that year. As a result, TBS-RAS had less time to begin the implementation of CDSR and lapsed $1 million in 2007–08. In 2008–09, TBS-RAS was subject to a spending freeze, resulting in a further lapse of $526,000. Table 3 provides an overview of spending; more detailed information is provided in Appendix F.

| Budgeted | Actual | Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a.Includes A-base but excludes Employee Benefit Plan and accommodation charges. | |||

| 2007–08 | $3,749.4 | $2,737.5 | $1,011.9 |

| 2008–09 | $4,978.6 | $4,452.5 | $526.1 |

Despite the delays in funding and limited resources, TBS-RAS managed to produce outputs such as reports, presentations, guides, tools and training (see par. 3.2.1) in the first two fiscal years. Many of the outputs have been produced at a lower cost than planned, thus demonstrating efficiency. Current gaps in the production of intended outputs appear to be caused by funding and resourcing issues, rather than inefficiency.

As noted in par. 3.2.1, performance reports are only available for the first two quarters of 2009–10. The limited performance data prevent the evaluation from fully assessing the economy of the CDSR. However, the data that do exist show that TBS-RAS has made progress in increasing the capacity of departments to meet CDSR requirements (i.e., the intended immediate outcome) at a lower cost than expected, thereby demonstrating economy.

Data were not available to quantify leveraging (i.e., the contribution of resources made by organizations relative to those provided through the CDSR). However, until summer 2009, the Centre of Regulatory Expertise and departments and agencies shared the cost of writing Regulatory Impact Analysis Statements, conducting cost-benefit analyses, and preparing Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plans, with a 30:70 split in effort. In addition, organizations are supplementing the work of TBS-RAS by creating tailored guides and using training budgets to send employees on CDSR-related training. This information indicates that leveraging was taking place, although its extent is not quantifiable.

3.3.2 Are There Any Alternative Design and Delivery Approaches That Should Be Considered for the Implementation of the Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation? Is the Centralized Approach, With Some Cost-Sharing Funds for Departments and Agencies, an Efficient Model?

Conclusion: No alternatives to the current design and delivery approaches were identified. The experiences of countries belonging to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) indicate that CDSR's centralized approach is an effective model for the implementation of regulatory policy.[6][7]

All of the interviewees from TBS-RAS and many of those from departments and agencies stated that the centralized approach used by TBS-RAS was the best one. Overall, departments and agencies value the advice and support provided by the Centre of Regulatory Expertise.

The experience of OECD countries shows that reforms to improve the quality of the regulatory system cannot be left solely to regulators, but that reforms can also fail if the system is too centralized. The OECD experience indicates that regulators must take primary responsibility, but within a system of incentives overseen by regulatory management and reform bodies. Such regulatory oversight bodies are often located in core government offices and have a mandate to ensure the quality of newly proposed rules and to develop programs for improving efficiency. Central oversight or coordination bodies encourage increased dialogue and interaction between the different ministries. Ultimately, however, the ministries themselves must commit to regulatory reform and ensure regulatory quality. In the Canadian context, TBS-RAS acts as the central oversight body for the CDSR, with the mandate to support ministers and departments in achieving regulatory efficiency and effectiveness. This role is consistent with the best practice centralized model identified through the international literature review.

4. Summary and Recommendations

4.1 Summary

Relevance: In establishing the External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation, and by implementing the CDSR to respond to its recommendations, the Government of Canada recognized the importance of regulations to the social and economic well-being of Canadians. The objectives of the CDSR continue to be aligned with federal government priorities and to address an identified need. These government regulatory priorities are identified in documents such as Budget Speeches, which call for regulatory approaches in specific areas, and are focused on achieving their intended objectives efficiently.

Performance—Effectiveness: A moderate level of success has been achieved to date. With a few exceptions (notably service standards), outputs such as training courses, advice and tools to support departments and agencies have been produced as planned. The need for improvements in the areas of partnerships and communications has been identified. In addition, there has been a moderate increase in the capacity of departments and agencies to meet CDSR requirements in the areas of interdepartmental and interjurisdictional cooperation, reduction of administrative burden, use of service standards, cost-benefit analysis, and performance measurement and evaluation. This increased capacity has resulted in levels of compliance with CDSR requirements of over 90% in most of these areas.

The level of success achieved to date is a result of the collaboration between TBS-RAS and departments and agencies. Making further progress on desired outcomes within the next two and a half years, including intermediate outcomes felt by regulated industries, will depend on whether departments and TBS-RAS can recruit and retain qualified personnel with the appropriate skills set or can access this expertise when needed, and on whether TBS-RAS has the resources required. A significant barrier to evaluating the extent to which these intermediate outcomes are achieved is the lack of performance measurement information. Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plans are required for high-impact regulations only, and this just since July 2009.

Performance—Efficiency and Economy: TBS-RAS was able to achieve the outputs and outcomes described above with limited resources and at a lower cost than originally expected, thus demonstrating both efficiency and economy (although the former is based on limited evidence). The current model, in which TBS-RAS acts as a central oversight body, is consistent with best practices in OECD countries. No alternatives were identified.

4.2 Recommendations

The recommendations for TBS-RAS can be grouped into three main areas:

- Ensuring that departments and agencies have adequate support going forward

- Increasing and improving communications

- Ensuring that reporting requirements are met

4.2.1 Support for Departments and Agencies

Despite limited resources, TBS-RAS has developed products that have allowed departments and agencies to increase their capacity to meet CDSR requirements. Additional increases in capacity can be achieved with more targeted support.

Recommendation 1: Address the remaining gaps in outputs, such as guidance on service standards.

Recommendation 2: Continue the current efforts to create pools of qualified cost-benefit analysts and regulatory experts to help ensure that departments and agencies have access to individuals with the appropriate skills set.

4.2.2 Communications

Products and services can help achieve increases in capacity only if they are known and used. TBS-RAS needs to focus on communicating more effectively with departments and agencies, as a number of them were unfamiliar with its products and services.

Recommendation 3: Establish an overall communications strategy for the CDSR. In particular, departments and agencies need to be made aware of TBS-RAS products and services, partnering efforts, and research and information-sharing initiatives.

4.2.3 Reporting

Reporting on production of outputs, use of financial resources, and achievement of outcomes is important for identifying:

- progress made with the resources used, for accountability purposes; and

- gaps in performance, in order to guide future plans.

Improvements are required so that reporting can be used as intended. Specifically, there are gaps in reporting, both on the use of funds allocated for CDSR implementation and on leveraged resources. In addition, departments and agencies need feedback from TBS-RAS on their progress in implementing the CDSR.

Recommendation 4: Ensure that reporting requirements are met and that departments and agencies include the level of additional resources (if any) expended to meet CDSR requirements. Full reporting will provide a government-wide picture of CDSR resource needs.

Recommendation 5: Complete departments' performance reports and communicate the results to ensure that departments and agencies receive the feedback needed.

Recommendation 6: Begin planning for the five-year evaluation within the next six months to ensure that a performance measurement strategy is in place and that appropriate data are captured in an ongoing, systematic and user-friendly manner.

Footnotes

[1] In addition to the support provided by the Centre of Regulatory Expertise, sixteen federal departments and agencies were allocated funds to develop internal capacity to implement the CDSR.

[2] To improve readability, the evaluation questions appear in a different order in section 3, “Conclusions and Supporting Findings.”

[3] Originally, as noted in Appendix A, the intent was to survey 80 department and agency contacts, but the actual number surveyed was 70.

[4] Smart Regulation: A Regulatory Strategy for Canada

[5] Detailed survey results are presented in Appendix E.

[6] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Building an Institutional Framework for Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA), 2008.

[7] Ibid. OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform—Regulatory Reform in Canada—Government Capacity to Assure High Quality Regulation, 2002.