ARCHIVED - Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada - Report

This page has been archived.

This page has been archived.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

2010-11

Departmental Performance Report

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

The original version was signed by

The Honourable Robert D. Nicholson, P.C., Q.C., M.P.

Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada

Table of Contents

Message from the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Section II: Analysis by Program Activities

- 2.1 Program Activity 1: Compliance Activities

- 2.2 Program Activity 2: Research and Policy Development

- 2.3 Program Activity 3: Public Outreach

- 2.4 Program Activity 4: Internal Services

Section III: Supplementary Information

Message from the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

I am pleased to present the Departmental Performance Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2011.

By pulling together our work under the Privacy Act and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, this report provides a unique overview of the past year. It reveals, among other things, the innovative ways in which we leveraged our resources for maximum impact, at home and abroad. For instance, we began the fiscal year by uniting with data protection authorities from nine nations to publicly challenge Google’s privacy practices. As the year went on, we linked up with domestic and international partners in data protection initiatives ranging from joint letters and resolutions to the development of online tools, the establishment of the Global Privacy Enforcement Network, and preparing for Canada’s new prohibition against unwanted electronic communications.

We also continued to focus on emerging challenges to privacy in four priority areas: public safety, information technology (IT), genetic information, and the protection of identity integrity. In IT, for instance, we dramatically bolstered our in-house expertise by recruiting specialized research analysts and establishing a dedicated IT test laboratory. We also published our findings in an audit of the government’s use of wireless networks and devices.

But, for all our forward focus, we tried never to lose sight of our founding mandate: to serve Canadians. We did that by strengthening our capacity to respond quickly and effectively to their inquiries and complaints. We also spoke to them where they live, work and learn, through outreach efforts, the creative use of social media, groundbreaking national consultations on online tracking, profiling and targeting and cloud computing, and regular interactions with the business community and the federal public service.

We reviewed Privacy Impact Assessments on numerous public safety measures and other government initiatives that matter to Canadians, and talked to Parliament about issues ranging from aviation safety and the long-form census to camera surveillance and open government. We also published an analytical framework for integrating privacy into public safety measures.

In October we opened an office in Toronto, where a significant number of Canadian businesses are headquartered. The new office is dedicated to strengthening compliance with privacy law among businesses in the region, further underscoring our commitment to serving Canadians.

Invariably, however, every achievement only whets the expectation for more. To meet such demand, we are retooling many of our processes. For instance, we now emphasize the early resolution of citizen complaints and focus our efforts on particularly complex or systemic issues. We have adopted a more systematic approach to the selection of privacy compliance audits, and have implemented mechanisms to strengthen our audit procedures. We have also developed a comprehensive document to help government officials understand our expectations for Privacy Impact Assessments.

Upon the three-year renewal of my term last December, I underlined that it is not enough to merely keep up with the changing privacy landscape; we must also anticipate and thoroughly understand developments, so as to better equip Canadians for the privacy challenges of tomorrow. This report describes the work of the past year that will help us meet that obligation.

The original version was signed by

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Section I: Overview

1.1 Summary Information

Raison d'être

The mandate of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada is to oversee compliance with both the Privacy Act, which covers the personal information-handling practices of federal government departments and agencies, and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), Canada's private-sector privacy law. The mission of the Office is to protect and promote the privacy rights of individuals[1].

Responsibilities

The Privacy Commissioner of Canada, Jennifer Stoddart, is an Agent of Parliament who reports directly to the House of Commons and the Senate. The Commissioner’s powers to further the privacy rights of Canadians include:

- investigating complaints, conducting audits and pursuing court action under two federal laws;

- publicly reporting on the personal information-handling practices of public- and private-sector organizations;

- supporting, undertaking and publishing research into privacy issues; and

- promoting public awareness and understanding of privacy issues.

The Commissioner works independently of other parts of the government to investigate complaints from individuals with respect to the federal public sector and the private sector. The focus is on mediation and conciliation, but if voluntary co-operation is not forthcoming, the Commissioner has the power to summon witnesses, administer oaths, and compel the production of evidence. In cases that remain unresolved, particularly under PIPEDA, the Commissioner may seek an order from the Federal Court to rectify the situation.

Strategic Outcome and Program Activity Architecture

In line with its mandate, the OPC pursues as its Strategic Outcome the protection of the privacy rights of individuals. Toward that end, the Office’s architecture of program activities is composed of three operational activities and one management activity. The PAA diagram below presents information at the program activity level:

| Strategic Outcome | The privacy rights of individuals are protected. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Program Activity | 1. Compliance Activities | 2. Research and Policy Development | 3. Public Outreach |

| 4. Internal Services | |||

Alignment of PAA to Government of Canada Outcomes

Federal departments are required to report on how their PAA aligns with Government of Canada Outcomes. The Privacy Commissioner, however, being independent from government and reporting directly to Parliament, is not obliged to make such alignment. The Strategic Outcome and the expected results from the work of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada are detailed in Section II of this Departmental Performance Report.

1.2 Performance Summary

The following table presents the OPC’s total financial and human resources for 2010-2011.

Financial and Human Resources

| * Funding for statutory obligations arising from the new anti-spam legislation, this was referred to in the 2010-2011 RPP as the Electronic Commerce Protection Act. | |||

| Planned Spending | Adjustment* | Total Authorities | Actual Spending |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23,239 | 974 | 24,213 | 22,824 |

| * Full-time Equivalents | ||||

| ** FTEs for statutory obligations arising from the new anti-spam legislation, this was referred to in the 2010-2011 RPP as the Electronic Commerce Protection Act. | ||||

| Planned | Actual | Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTEs | Adjustment** | Adjusted FTEs | ||

| 173 | 4 | 177 | 160 | (17) |

As of March 31, 2011, the Office had 160 employees. The variance of 17 FTEs is attributed in part to the late Royal Assent of the new anti-spam legislation where the staffing has been delayed and in part to a normal turnover rate of staff.

Contribution of Priorities to the Strategic Outcome

In 2010-2011, the OPC had five corporate priorities, which are listed in the table below. Work to advance each priority contributed to progress toward the Office’s Strategic Outcome. For each priority, the following table presents a summary of actual performance and a self-assessment of performance status, based on the Treasury Board Secretariat’s scale[2] of expectations. More detailed performance information is provided in Section II – Analysis by Program Activity.

| OPC Priorities for 2010-2011 | Type[3] | Performance Summary | Performance Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Redefine service delivery through innovation to maximize results | New |

The OPC created a robust intake unit to prioritize incoming complaints and allocate an appropriate level of resources for their effective resolution. As a result, concerned Canadians obtained faster responses to their complaints than in the past. Of the combined total of 899 complaint files closed in 2010-2011 (Privacy Act: 570, PIPEDA[4]: 329), 18 percent (Privacy Act: 78, PIPEDA: 80) were resolved quickly when the new intake unit applied early-resolution strategies. Because these cases did not require time-consuming formal investigations, they were closed on average in just 3.2 months. By comparison, cases that required formal investigations took an average of 11.8 months to close--eight months on average for Privacy Act complaints and 19.2 months for PIPEDA complaints. The Office worked with inter- and intra-departmental committees to prepare for the implementation of Canada's new anti-spam law, which was passed in December 2010. Frameworks are being devised to integrate the new powers allocated to the Commissioner as a result of this law. The OPC also worked with provincial and territorial counterparts on shared privacy issues, including:

The Office joined privacy enforcement agencies from around the world to establish the Global Privacy Enforcement Network (GPEN), a network designed to facilitate cross-border cooperation in the enforcement of privacy laws. |

Met all |

| 2. Provide leadership to advance four priority privacy issues (information technology, public safety[5] , identity integrity and protection, and genetic information) | Previous | In 2010-2011, the Office engaged in a variety of activities (publications, speeches, website content and media relations) to raise awareness of the four priority privacy issues among the public and other key stakeholders. The OPC published and distributed a new brochure about the four

priorities, to better explain what they are, why the OPC identified these priorities, and why others should be concerned about them as well. The OPC also undertook actions specific to each priority area in 2010-2011: Information technology: The OPC developed two fact sheets on protecting privacy on mobile devices, as well as an information document entitled, Data at Your Fingertips: Biometrics and the Challenges to Privacy. It also prepared several blog posts related to technical privacy issues, and organized industry briefings on a wide range of topics, such as biometrics, cloud computing, social network attacks, video surveillance and cyber security, significantly increasing the level of understanding of these issues within the organization and beyond. Public safety: The OPC developed a policy reference document: A Matter of Trust: Integrating Privacy and Public Safety in the 21st Century. This and related activities allowed the OPC to deepen its knowledge in the area, as reflected in speeches, analysis of crime bills, PIAs, appearances before Parliament, and other work. Identity integrity and protection: The OPC made a submission to the Digital Economy Consultation, led by Industry Canada. It also commissioned research on the public/private divide, identity management systems, privacy and developing countries, and the use of social media in government. The Office also created a speakers series to examine emerging privacy issues and commissioned papers from four speakers. Genetic information: The OPC commissioned the first part of a major research paper on the use of genetic information in the insurance context, prepared a draft fact sheet on direct-to-consumer sale of genetic testing services, and partnered with Genome Canada in a workshop series on genetic information called GPS – Where Genomics Public Policy and Society Meet. |

Met all |

| 3. Strategically advance global privacy protection for Canadians | Previous | This year, the Commissioner continued as Chair of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Volunteer Group on Privacy, mandated to assist the OECD in reviewing its Privacy Guidelines. The OPC provided staff to the OECD to help it mark the 30th anniversary of its Guidelines in advance of the review. The OPC was a founding member of the Global Privacy Enforcement Network and joined the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation (APEC) cross-border privacy enforcement initiative. The OPC continued to play a key role in the work of the International Standards Organisation (ISO) on identity management and privacy technologies. A member of the OPC sits on the Commission for the Control of INTERPOL’s Files. The OPC supported work on international resolutions that Canada sponsored, namely through involvement in the Accountability Project resulting from the 2009 International Data Protection Commissioners Conference in Madrid. The Office was also involved in activities of the Association francophone des autorités de protection des données personnelles, as well as in the Ibero-American Data Protection Forum. Throughout the year, the OPC received officials on fact-finding missions from foreign data protection authorities. The Office worked with other data protection authorities on common responses to global privacy concerns, such as the posting of personal information without consent during the launch of Google Buzz. The OPC also provided input to international organizations and associations prior to their launch of products and initiatives that could have an impact on privacy. |

Met all |

| 4. Support Canadians, organizations and institutions to make informed privacy choices | Previous | During 2010-2011, the OPC produced resource tools and organized outreach activities for several target audiences, including small-business owners, youth, and federal public servants. The Office expanded its outreach activities in Ontario through the opening of its Toronto regional office. As well, the Office launched a new speakers series titled Insights

on Privacy, and held public consultations in Toronto, Calgary and Montreal on privacy and online tracking, profiling and targeting, as well as cloud computing. The past year saw an increase in requests for OPC materials, visits to its website, and engagement through social media. The Office experimented with new methods to provide guidance and information to Canadians and organizations, including online video, interactive web tools, armchair discussions, and collaborative events. The OPC contributed to the international data protection community’s adoption of an international resolution on the importance of “Privacy by Design”. |

Met all |

| 5. Enhance and sustain the organizational capacity | Ongoing | The OPC continues to explore new approaches to recruitment and retention, such as through the use of social networking sites, and to expand the use of technology to develop knowledge-sharing tools. The Office participates in government-wide initiatives, including the move toward a more robust system for the management of human resources, the promotion of the Government of Canada Employee Passport approach, and the Common HR Business Processes. The effort to build more SharePoint sites within the Office has continued in 2010-2011, contributing to increased knowledge sharing, collaboration and synergy between organizational units. Several business processes were automated, particularly in the audit and the communications units, further facilitating the exchange of information and data. The OPC is now able to envisage the automation of its scorecard management tool, which has been maintained manually until now. The Office developed a long-term accommodation strategy by defining each organizational unit’s business requirements. The project was undertaken with Public Works and Government Services Canada, the entity charged with identifying an appropriate location for a move in 2013. |

Met all |

All commitments made to advance the five OPC corporate priorities in 2010-2011, as published in the 2010-2011 Report on Plans and Priorities, have been “met”.

Risk Analysis

External Factors

Canadians should be well aware that online risks and threats to personal information are very real. Digital information and systems are inherently vulnerable when interconnected and made globally accessible. Security problems, particularly cybercrime and cyber-espionage, are threatening our private and public e-infrastructures. A lack of industry standards undermines the security of services in the cloud. Service providers are taking advantage of the rapid product development opportunities, with privacy becoming an afterthought. Small and medium-sized businesses are using digital technologies without the education and tools needed to effectively safeguard personal information.

These threats are compounded by our ever-increasing reliance on online services and our propensity for sharing personal information. By embracing new technologies, Canadians of all ages, and youth in particular, are challenging and reshaping traditional notions of privacy. The effects on our society cannot easily be measured. The lines between our public and private selves are becoming blurred, particularly for our children, who are growing up in a digital world. Digital literacy programs that teach children and their parents to properly assess and mitigate online privacy risks are slowly gaining traction.

But, in the meantime, people’s online sharing behaviours continue to be a privacy concern. Individuals are not only using new forms of technology to communicate with each other, but also for everyday activities, such as banking and online shopping. Online financial transactions involve sensitive information, so the security and privacy of these transactions, particular when they are conducted from home computers and mobile devices, is essential to trust in the systems.

The global data protection community has recognized it needs to revisit and reaffirm first principles in the privacy arena. Too much time has now passed since first- (even second-) generation privacy laws and guidelines were arrived at in the 1970s for these to be resonant with younger citizens. A whole new generation of awareness around privacy, information ethics, data protection and online security needs to be re-launched, with citizens, schools, companies and government all playing a part.

Also clear is that advanced and ubiquitous digital surveillance and the global interception industry have grown enormously in the past decade. These technologies, when widely deployed, have a profound effect on civil liberties and human rights.

Governments are able to engage in the wholesale capture of individuals’ digital trail: SMS, text, geo-location, e-mail, to name just a few of the ways people can be tracked. The commercial potential, network capacity and technological scope for online monitoring have few remaining practical limits – aside from the law. Inexpensive bandwidth, expansive storage, ubiquitous devices and innocuous sensors are all driving the trend towards more surveillance and online tracking.

Faced with the shadow of cybercrime and the growth of cyber-surveillance, the risk is that trust may become the depleting resource of cyberspace.

Bandwidth and capacity were once the overriding technical preoccupations, but these have been supplanted by wider social issues of suspicion, surveillance and self-censorship. While there are no simple responses to these issues – whether they involve the mass screening of travellers or automated exchange of data across borders--a wide campaign of safeguards and solutions to these privacy risks is overdue. Government practices and laws must be adapted, commercial products and services better regulated, individual citizens better educated and empowered in the hopes they can secure their own data and online practices, and international standards agreed to, observed and enforced.

Personal information sharing on a mass scale represents a tectonic shift in social mores and behaviour. All networked societies are struggling to come to terms with the implications – in their companies and courtrooms, in their governments and global relations, in their schoolyards and studios. While the norms of social networking are slowly emerging, almost half of Canadians now use platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. These tools are dramatically changing the way people share information. Where people communicate, what they relate, when and why they share - all these are being reshaped by new channels, just as social networks have accelerated the transformation of personal information into a raw commodity for use by advertisers, data brokers, insurers and other commercial sectors.

Analytics—the use of new software tools to mine data for unexpected trends or patterns—have opened the door to unforeseen ethical considerations. As these technologies evolve, the contexts and definitions of “personal information” are also being revisited. Developments in geo-location, biometrics, genetics and online analytics call for a common understanding of the term and a return to basic privacy principles.

More broadly, protecting privacy in this rapidly transforming online landscape demands agile, creative and effective responses. Realistic guidance from regulators is increasingly important. Therefore, data protection authorities and other regulators are actively developing guidance and rules, in consultation with technological innovators, consumers and legal scholars and specialists. This trend reflects the global dimension of contemporary privacy issues. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission, the OPC and the European Union have all conducted consultations in the past year on data protection issues arising from a growing reliance on the Internet for communication, commerce and innovation.

Key Business Risks

Three areas were identified as critical risks in the 2010-2011 Report on Plans and Priorities and, as such, have been managed to mitigate their possible effects on the OPC. Two critical risks pertained to the OPC’s organizational capacity—in particular the capacity to address a high business demand for services, and to eliminate the long-standing backlog of investigation files. These risks were mitigated through a multi-pronged approach that included diligently allocating the additional funding received from Treasury Board to priority activities; applying an assortment of aggressive procedures to close backlogged files before March 31, 2010; employing innovative human resources management techniques to recruit, train and retain staff in a highly competitive market; and a major re-engineering project to streamline work processes, including the use of alternative interventions to respond to demands more efficiently. The Office continues to invest in streamlining its operations.

The third critical risk the Office was managing in 2010-2011 related to the protection of the OPC’s own data holdings against breaches, either due to system or human error. The OPC continues to manage this risk with due diligence. In 2010-2011, a threat and risk assessment was performed and corrective actions are being implemented. A business continuity plan developed in 2009-2010 was tested in 2010-2011 and will be reviewed again in 2011-2012. The testing of the plan led to the identification of some areas requiring attention, which are currently being addressed.

During 2010-2011, an organizational security program was prepared to outline new and existing security measures. Information about the secure handling of data was incorporated in the OPC employee orientation process. All staff participated in a security information session in November 2010 and will be expected to review, on an annual basis, the newly purchased computer-based training material on the OPC’s security and information-management needs.

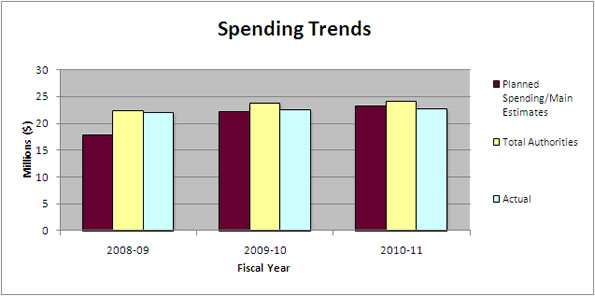

Expenditure Profile

The OPC Main Estimates and Planned Spending amounts (presented as a single figure since there is no significant difference between the amounts) increased by $1.230 million from 2008-2009 to 2009-2010 following the approval of new funding from Business Case II. These funds were earmarked to address complaint investigations, expand public outreach, and implement a new internal audit initiative.

Many public outreach initiatives were directed at businesses and other target groups such as small businesses and youth. The OPC also now has an internal audit function. The increase between 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 spending authorities of $0.9 million is related to the passage into law of the new anti-spam legislation received in December 2010.

Voted and Statutory Items

For information on the OPC votes and statutory expenditures, refer to the 2010–2011 Public Accounts of Canada (Volume II).

Section II: Analysis by Program Activity

OPC Performance in 2010-2011

| Expected Result | Performance Indicator | Target |

|---|---|---|

| Ultimate Outcome for Canadians | ||

| The OPC plays a lead role in influencing federal government institutions and private-sector organizations to respect the privacy rights of individuals and protect their personal information. | Extent and direction of change in the privacy practices of federal government institutions and private-sector organizations. | Note: Baseline data being developed in 2009-2010 will be used to set a target level for this indicator during 2010-2011. The target will be published in the 2011-2012 RPP. |

The OPC’s performance against the above indicator will be reported starting in next year’s Departmental Performance Report, against the target set in the 2011-2012 Report on Plans and Priorities. Until then, progress toward the Strategic Outcome is informed by the performance achieved under the four Program Activities of the OPC Program Activity Architecture. For each Program Activity, subsections 2.1 to 2.4:

- describe what is involved in the Program Activity (defined as per the implementation of the TBS Management, Resources and Results Structure Policy);

- report on planned versus actual resource use in 2010-2011;

- present a summary of the OPC actual performance in relation to expected results and performance indicators/targets, and include a performance status against the TBS scale (refer to section 1.2 for a description of the scale); and

- provide an overall analysis of the OPC’s performance in 2010-2011, discuss lessons learned from the past year’s performance, and articulate the benefits that Canadians derive from the activities delivered by the OPC.

2.1 Program Activity 1: Compliance Activities

Activity Description

The OPC is responsible for investigating privacy-related complaints and responding to inquiries from individuals and organizations. Through audits and reviews, the OPC also assesses how well organizations are complying with requirements set out in the two federal privacy laws, and provides recommendations on Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs), pursuant to Treasury Board directive. This activity is supported by a legal team that provides specialized advice and litigation support, and a research team with senior technical and risk-assessment support.

|

2010-2011 Financial resources ($000) |

2010-2011 Human resources (FTEs) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned Spending | Total Authorities | Actual Spending | Planned | Actual | Difference |

| 9,198 | 9,791 | 9,938 | 88 | 78 | (10) |

The actual spending includes reallocations between activities to better reflect Program activity spending.

| Expected Results | Performance Indicators/Targets | Actual Performance | Performance Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate Outcomes | |||

| Federal government institutions and private-sector organizations meet their obligations under federal privacy legislation and implement modern practices of personal information protection. | Indicator: Extent to which investigation and audit recommendations are accepted and implemented over time Target: 90 percent of 'well-founded', 'resolved' and 'well-founded and resolved' investigation recommendations are accepted and implemented |

Investigations under the PIPEDA In 2010-2011, the Commissioner made 35 recommendations in investigations that were either ‘well-founded’, ‘resolved’ or ‘well-founded and resolved’. All recommendations (100 percent) were accepted and 83 percent were implemented. The six remaining recommendations are scheduled for follow-up on implementation by June 2011. Investigations under the Privacy Act In 2010-2011, the Commissioner made nine recommendations in investigations that were either ‘well-founded’, ‘resolved’ or ‘well-founded and resolved’. Of those recommendations, 89 percent were accepted, although none had been implemented by the end of the fiscal year. Follow-up work continues to monitor progress on five of the nine recommendations, and an audit was launched to determine the status of the other four. |

Mostly met |

| Target: 90 percent of audit recommendations are accepted fully by entities; upon re-audit, two years after the initial report, action to implement has begun on 90 percent of recommendations | Sixteen recommendations were included in the three audits[6] that were made public in 2010-2011 and all (100 percent) were accepted by the audit entities at the time of reporting. In 2010-2011, the OPC followed up on three audits that were conducted in 2008 and 2009, to determine how many of the recommendations had been implemented. Action was reported to have begun on 33 of the 34 recommendations (97 percent). |

Exceeded | |

| Indicator: Extent to which obligations are met through litigation Target: Legal obligations are met in 80 percent of cases, either through settlements to the satisfaction of the Commissioner or court-enforced judgments |

During 2010-2011, the OPC was involved in 14 litigation cases related to PIPEDA and six cases related to the Privacy Act in order to promote compliance with federal privacy legislation. | Not applicable[7] | |

| Immediate Outcomes | |||

| Individuals receive timely and effective responses to their inquiries and complaints. | Indicator: Timeliness of OPC responses to inquiries and complaints Target: See footnote[8] |

The Office responded to 11,165 inquiries (oral and written) in 2010-2011, a 43 percent increase over the previous year. Of those, 91 percent were dealt with within 30 days. Inquiries not responded to within the service standard were more complex and either required a legal opinion or additional information to respond to the client. The timeliness of responses to complaints[9] is measured from the date a complaint is received to the date findings are made or another type of disposition (including early resolution without an investigation) occurs:

|

Met all |

| The privacy practices of federal government institutions and private-sector organizations are audited and the Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) submitted by federal institutions are reviewed to determine compliance with federal privacy legislation and policies. | Indicator: Proportion of audits and PIA reviews completed within planned times Targets[10]: 50 percent of audits are completed within planned times and 50 percent of PIA reviews are completed within 90 days of initiation |

Three audits[11] and three follow-ups to previous audits[12] were approved and published and/or substantially completed in 2010-2011, as per the approved plan (i.e., 100 percent). | Exceeded |

| Given limited resources in 2010-2011, 35 percent of PIA reviews were responded to within the planned timelines through letters of recommendations. The Office, however, provides advice and guidance on PIAs through consultation meetings, telephone conversations and e-mail exchanges in advance of sending a formal letter of recommendations. | Somewhat met | ||

| Indicator: Responsiveness of (or feedback from) federal government departments and private sector organizations to OPC advice relating to PIAs and interventions Targets: 75 percent of institutions and organizations are responsive to the OPC advice |

During 2010-2011, the OPC reviewed 12 PIAs for initiatives that involved privacy risks judged to be particularly intrusive, and sent letters of recommendations to add privacy protections to those initiatives. By March 31, 2011 the OPC had received nine written replies (75 percent) from federal institutions that responded to the OPC guidance by agreeing to adopt additional privacy-protective measures or to revisit their initiatives. The Office continues to monitor initiatives that pose significant risks to privacy. | Met all | |

Performance Analysis

The OPC has successfully implemented new processes to respond more quickly to complaints from Canadians, thereby making better use of public funds invested in the Office.

A new method to assign internal resources based on priority and complexity of complaints allows more resources to be allocated to systemic privacy issues.

Similarly, a new inquiries reporting and analysis tool that captures emerging privacy issues and trends now enables the Office to better share critical information between the inquiries unit and other areas of the organization.

Audits were undertaken in line with a new risk-based audit plan. Under the plan, organizations to be audited are selected on a more methodologically sound basis, built on extensive consultations, documentary reviews and environmental scanning, and aligned with the OPC priority privacy issues. Consequently, the OPC invests audit resources on projects of greatest risk to privacy. As well, auditors now follow a manual, completed in 2010-2011, to ensure that privacy audits respect the spirit of generally accepted audit standards.

The work to strengthen the Privacy Impact Assessment review process was started last year and finalized in 2010-2011. A triage method is now applied to focus on PIAs for initiatives that represent the highest privacy risks, given that resources are not available to review all PIAs at this time. Despite prioritizing PIAs, the Office was not able to meet its performance target of 90 days to reviews PIAs, as staffing continues to be a challenge in this unit. Staffing actions are being completed to achieve a full complement of PIA staff and, in turn, to improve the timeliness of formal responses to institutions.

The Office did not implement a quality-assurance program for the complaints-resolution process as initially envisaged for this reporting period. However, a review of the complaints-resolution process is under way to ensure it can accommodate increasingly complex and challenging investigations.

Lessons learned

Investment in the intake process for complaints has yielded measurable efficiencies. Building on the recent re-engineering effort, more opportunities are being considered to further streamline investigation processes and systems. Organizational changes are now being introduced to better align resources with the specific needs of investigations, thus improving service delivery.

Investments to settle unresolved complaint files before they reach the Court have also resulted in more effective compliance with PIPEDA in 2010-2011. As well, collaboration with provincial and territorial counterparts continues to achieve a more harmonized oversight of private-sector privacy law.

Over the past two fiscal years, the OPC has held PIA workshops, each attended by more than 100 federal employees. These workshops are, among other things, perfect opportunities to encourage departments to engage the Office early in the PIA process. By incorporating OPC’s advice about appropriate privacy measures at the design stage of an initiative, less effort is later required to review the formal PIA.

Benefits for Canadians from Program Activity 1

In responding to inquiries, the OPC informs Canadians of their privacy rights. In conducting complaint investigations, audits and PIA reviews, the Office establishes whether government institutions and private-sector organizations plan to and/or collect, use, disclose, retain and dispose of Canadians’ personal information in accordance with the privacy protections set out in the two federal privacy laws. Where non-compliance is identified, the OPC takes action to influence change. Investigating one individual's privacy complaint or auditing an organization’s privacy practices can have a huge impact when it leads to improvements that affect many Canadians.

2.2 Program Activity 2: Research and Policy Development

Activity Description

The OPC serves as a centre of expertise on emerging privacy issues in Canada and abroad by researching trends and technological developments, monitoring legislative and regulatory initiatives, providing legal, policy and technical analyses on key issues, and developing policy positions that advance the protection of privacy rights. An important part of the work involves supporting the Commissioner and senior officials in providing advice to Parliament on potential privacy implications of proposed legislation, government programs and private-sector initiatives.

| 2010-2011 Financial resources ($000) | 2010-2011 Human resources (FTEs) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned Spending | Total Authorities | Actual Spending | Planned | Actual | Difference |

| 5,058 | 5,316 | 3,220 | 18 | 18 | 0 |

The actual spending includes reallocations between activities to better reflect Program activity spending.

| Expected Results | Performance Indicators/Targets | Actual Performance | Performance Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate Outcome | |||

| Parliamentarians and key stakeholders have access to clear, relevant information and timely and objective advice about the privacy implications of evolving legislation, regulations and policies. | Indicator: Value added to stakeholders of the OPC information and advice on selected policies and initiatives Target: 75 percent effectiveness in adding value to public- and private-sector stakeholders through the OPC’s information and advice on their policies and initiatives |

The OPC held three successful national consultations in Toronto, Montreal and Calgary, bringing together stakeholders on some of the most important emerging issues in privacy – challenges and opportunities in consumer tracking, behavioural advertising, online games and the privacy implications of emerging technologies, and cloud computing. Stakeholders came from industry, government, consumer associations, civil society and other interested parties, and had positive feedback on the consultations. There was also discussion over whether PIPEDA can meet the challenges raised by these emerging issues. A draft report for further consultations was issued in October 2010, and a final report was to be issued in May 2011. With counterparts from other jurisdictions in Canada, the Office submitted a joint federal-provincial-territorial letter to the Deputy Minister of Public Safety Canada with regard to proposed lawful access legislation. A copy of the letter was tabled through the House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics (ETHI) and to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice, Human Rights, Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness and Subcommittee on Public Safety and National Security. The Office collaborated with federal partners and international counterparts to prepare for and implement Canada’s anti-spam law, Bill C-28, which received Royal Assent in March 2011. The Office developed, in consultation with key stakeholders, a guidance document, entitled A Matter of Trust: Integrating Privacy and Public Safety in the 21st Century, which was submitted to several parliamentary committees and subcommittees (ETHI, Public Safety and National Security). |

Met all [Note: Performance against this indicator is assessed qualitatively, based on the information provided here rather than numeric target, which is currently being revisited] |

| Immediate Outcomes | |||

| The work of Parliamentarians is supported by an effective capacity to identify privacy issues, and to develop privacy-respectful policy positions for the federal public and private sectors. | Indicator: Value added to Parliament of the OPC views on the privacy implications of relevant laws and regulations Target: 75 percent effectiveness in adding value to Parliamentarians from the OPC views on relevant laws and regulations |

In 2010-2011, the OPC made 15 appearances before seven different parliamentary committees to provide views and advice on the privacy implications of new legislation or ongoing programs. Various subject areas were addressed, including camera surveillance, aviation security, consumer product safety, the census and open government. The OPC reviewed 30 bills,

including 16 intensively, and interacted with Members of Parliament on 42 occasions. In December 2010, Parliament approved Commissioner Stoddart’s reappointment as head of the OPC for a further three years – a clear demonstration of the value that Members of Parliament see in her role and contribution to their deliberations. |

Met all [Note: Performance against this indicator is assessed qualitatively, based on the information provided here rather than numeric target, which is currently being revisited] |

| Knowledge about systemic privacy issues in Canada and abroad is enhanced through information exchange and research, with a view to advancing privacy files of common interest with stakeholders, raising awareness, and improving privacy-management practices | Indicator: Stakeholders have had access to, and have considered, OPC research products and outreach materials in their decision-making Target: Initiatives under all four OPC priority privacy issues (100 percent) have involved the relevant stakeholders and there is documented evidence that they were influenced by OPC research products and outreach materials |

The OPC conducted research in support of its ongoing compliance activities. It also examined emerging privacy trends in areas such as the public/private divide and its effects on people’s reputation, payment systems, advanced sensor networks, biometrics, applications and mobile devices. Research and other knowledge-advancement activities were conducted in all four priority

privacy issue areas (refer to section 1.2, the Performance Summary of this Report, under Priority 2), involving relevant stakeholders, such as subject-matter experts in academia and industry, who benefit from the outcome of the OPC research work. Through this work, the OPC has deepened its knowledge about systemic privacy issues, which was then reflected in speeches, legal and policy

analysis, PIAs, appearances before Parliament, and other work. Also in 2010-2011, the OPC commissioned two university professors to study the powers and functions of the ombudsman model with respect to the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. The Office’s Contributions Program, which funds privacy research and public education initiatives related to PIPEDA, awarded nearly $500,000 for projects in 2010-2011 (see full list of recipients). This year again, the research initiatives focused on the Office’s four privacy priority areas: information technology, public safety, identity integrity and protection, and genetic privacy. More specifically, the work pertained to the following areas of interest to Canadians and others around the world:

|

Met all |

Performance Analysis

With privacy emerging as an important concern in the day-to-day lives of Canadians, the OPC encouraged and enhanced the privacy dialogue on a national and international scale. Such dialogue permits the dissemination of important new privacy-related knowledge. It also continues to inform the OPC research agenda in emerging fields such as the divide between the public and private realm online, behavioural advertising, and the privacy implications of cloud computing.

Lessons learned

Part of the organizational restructuring that started in late 2010-2011 involved uniting the research and policy development units for greater synergy and collaboration. A research plan is now being developed in conjunction with all branches. The aim is to derive the most from the OPC’s research activities, both to further enhance knowledge of privacy issues within the Office, and to leverage the knowledge by translating it into useful information for Canadians. The OPC also continues to seek opportunities to partner with other public, private, and not-for-profit organizations with similar goals of promoting privacy protection.

Benefits for Canadians from Program Activity 2

By studying the privacy implications of public- and private-sector policies, initiatives and processes and developing positions for consideration by stakeholders that are respectful of privacy, the OPC advances knowledge about privacy issues and emphasizes the protection of privacy rights of individuals in Canada and abroad.

2.3 Program Activity 3: Public Outreach

Activity Description

The OPC delivers public education and communications activities such as speaking engagements and special events, media relations, and the production and dissemination of promotional and educational material. Through public outreach activities, individuals have access to information that enables them to protect their personal information and exercise their privacy rights. The activities also allow organizations to understand their obligations under federal privacy legislation.

| 2010-2011 Financial resources ($000) | 2010-2011 Human resources (FTEs) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned Spending | Total Authorities | Actual Spending | Planned | Actual | Difference |

| 3,846 | 3,701 | 3,283 | 25 | 21 | (4) |

The actual spending includes reallocations between activities to better reflect Program activity spending.

| Expected Results | Performance Indicators/Targets | Actual Performance | Performance Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate Outcomes | |||

| Federal government institutions and private-sector organizations understand their obligations under federal privacy legislations and individuals understand how to guard against threats to their personal information. | Indicator: Privacy outcome for government initiatives or programs from the PIA consultations/ recommendations Target: In 70 percent of the government initiatives or programs for which a high-priority PIA was reviewed and a recommendation was issued, a privacy protection was added after the consultations/ recommendations from the OPC |

During 2010-2011, the OPC reviewed 12 PIAs for initiatives that involved a particularly high risk to privacy and sent letters of recommendations to add privacy protections to those initiatives. By March 31, 2011 the OPC had received nine written replies (75 percent) from federal institutions that responded to the OPC guidance by agreeing to adopt additional privacy-protective measures or to revisit their initiative. Not all federal departments may have had the time to respond by the end of the fiscal year. The Office continues to monitor initiatives that pose significant risks to privacy. | Exceeded |

| Indicator: Extent to which private-sector organizations understand their obligations under federal privacy legislation Target: More than 40 percent of private-sector organizations report having at least moderate awareness of their obligations under PIPEDA |

A survey conducted by EKOS Research Associates on behalf of the OPC (results were published in May 2010) revealed that almost half (47 percent) of the businesses surveyed reported having a high degree of awareness of their responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws. | Exceeded | |

| Immediate Outcomes | |||

| Individuals have relevant information about privacy rights and are enabled to guard against threats to their personal information. | Indicator: Reach of target audience with OPC public education activities Target: 100 media citations of OPC officials on selected communications initiatives per year At least 100,000 hits per month on the OPC website and 20,000 hits per month to the OPC blog At least one news release per month on a subject of particular interest to individuals At least 350subscribers to the e-newsletter At least 1,000 communication tools distributed per year Two public education initiatives annually, designed for new individual target groups Two public events addressing needs of individual target groups |

The OPC continued to be referenced widely in media coverage, in Canada and abroad. The volume of citations in 2010-2011 well surpassed 100. Both OPC annual reports received generous coverage, as did its privacy compliance audits and other announcements, such as the conclusions of the Facebook and Google Wi-Fi investigations, and a joint letter with other data

protection authorities regarding the Google Buzz matter. The OPC website and main blog saw an increase in the number of visits in 2010-2011 over last year, with more than 2.8 million unique visitors—an average of 230,000 per month. Two or more news releases were issued per month in 2010-2011 on subjects of interest to both individuals and organizations. As of March 31, 2011, the OPC had 1,013 subscribers (including individual and organizational subscribers) to the e-newsletter. Approximately 19,000 publications were distributed in 2010-2011, up from 16,000 the year before. This includes 12,000 calendars featuring popular editorial cartoons. The OPC delivered a series of presentations to more than 21,000 students, educators and parents on the privacy risks of social networking. The OPC engaged Canadians on privacy through the use of social media tools: in 2010-2011, the Office produced 73 posts on its two blogs and 581 tweets; more than doubled the number of followers to the OPC Twitter account (@PrivacyPrivee) compared to last year, bringing its total followers to 2,376; added 23 new videos to the OPC YouTube channel, including a video for small businesses on customer privacy. The Office created a series of armchair discussions to showcase new voices in the privacy field. Two events were held in 2010-2011, attracting a total of more than 100 participants and almost 700 views on YouTube. |

Exceeded |

| Indicator: Extent to which individuals know about the existence/role of the OPC, understand their privacy rights, and feel they have enough information about threats to privacy Targets: At least 20 percent of Canadians have awareness of the OPC At least 20 percent of Canadians have an "average" level of understanding of their privacy rights At least 35 percent of Canadians have some awareness of the privacy threats posed by new technologies |

In a Harris/Decima poll conducted on behalf of the OPC in 2010-2011, involving 2,000 respondents from across Canada:

|

Exceeded | |

| Federal government institutions and private-sector organizations receive useful advice and guidance on privacy rights and obligations, contributing to better understanding and enhanced compliance. | Indicator: Reach of organizations with OPC policy positions, promotional activities and promulgation of best practices Targets: At least 1,000 communication tools distributed per year At least one news release per month on a subject of particular interest to organizations Exhibiting at least four times during the year At least 350 subscribers to the e-newsletter Two public education initiatives annually designed for new organizational target groups Two public events/speaking engagements addressing needs of organizational target groups |

In 2010-2011, the OPC produced about 25 distinct tools and publications, including annual reports and audits, guidance on biometrics, and a summary of research on youth online privacy. The OPC redesigned and launched the “Privacy For Small Business Online Tool” to help

small businesses build a privacy plan. Since its launch in October 2010, the online tool has been used by almost 8,000 visitors. The OPC also published a document, called Expectations: A Guide for Submitting Privacy Impact Assessments to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, to guide federal entities covered under the Privacy Impact Assessment Directive on what the Office looks for in PIA reviews. To support Data Privacy Day 2011, the OPC developed a suite of products aimed at encouraging the protection of electronic data. These products, which included a poster, stickers and fact sheets on privacy and mobile devices, were distributed to all provincial and territorial commissioners for their use in Data Privacy Day activities. Those products were among the 34,007 communication tools distributed to various audiences in 2010-2011. Two or more news releases per month were issued in 2010-2011 on subjects of interest to both organizations and individuals. The Office exhibited at 13 events in 2010-2011, a 30-percent increase over the previous year. As of March 31, 2011, the OPC had 1,013 individual and organizational subscribers to the e-newsletter. In 2010-2011, the OPC organized the first-ever Privacy Practices Forum for federal departments to share tools, techniques and experiences for enhancing privacy protection. OPC representatives spoke at 148 events over the past fiscal year, including delivering keynote speeches at GTEC 2010 in Ottawa and the OECD Conference on Privacy, Technology and Global Data Flows in Jerusalem. |

Exceeded |

Performance Analysis

With its growing numbers of public education, outreach and communications activities, the OPC is reaching out to more and more organizations, both in the public and private sectors, and to individuals. Awareness of privacy obligations and rights is increasing, but given the new privacy challenges emerging almost daily, more work is needed to disseminate information and tools.

On the international scene, the Office attracted widespread media coverage of its investigation into Google’s collection of Canadians’ personal information from unsecured wireless networks, as well as the follow-up on an investigation of Facebook’s privacy policies and practices. As well, the Privacy Commissioner and Assistant Commissioner made presentations at several international conferences and events where global organizations were present. These included, for example, presentations to the Privacy Laws and Business 23rd Annual Conference in Cambridge, UK, the ITechLaw 2010 World Technology Law Conference in Massachusetts, U.S.A., and the International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners in Jerusalem.

Furthermore, during 2010-2011, the OPC:

- began discussions with provincial and territorial privacy counterparts to develop localized and targeted programs in their jurisdictions that are focused on heightening small business awareness of privacy issues and safeguards, as well as digital literacy among Canadians, particularly the young, to raise awareness about the privacy risks inherent in online activities;

- developed and implemented public outreach initiatives aimed at young people, including inviting a youth advisory panel to help identify the knowledge gaps among youth, and delivering presentations to students, educators and parents on the privacy risks of online social networking;

- bolstered engagement with stakeholders in the Greater Toronto Area with the opening in 2010 of a regional office in Toronto by, among other things, establishing collaborative networks with the business community to support current and future outreach activities and holding a series of information sessions with businesses and privacy practitioners;

- in the context of the new Treasury Board Secretariat Directive on PIAs taking effect April 1, 2010, developed and communicated guidance on privacy for federal public servants, including providing an overview of the Privacy Act, reviewing the role of the OPC in reviewing PIAs, highlighting relevant TBS guidelines, and outlining best practices in the day-to-day handling of personal information. To support this work, the OPC developed a strategic communications plan and conducted a series of executive interviews with Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) coordinators;

- spearheaded an initiative with nine other international data protection authorities to remind Google and other online companies that they are obliged to comply with the laws of the countries in which they launch their products and services. The joint letter and news conference in Washington received media coverage around the globe.

Lessons learned

In 2010-2011, the OPC leveraged the attention and credibility generated in part by the 2009 Facebook investigation to further raise awareness of privacy rights and obligations in the public and private sectors, in Canada and abroad. In light of its increased profile, the Office is more cognizant than ever of the impact its efforts may have. As such, the OPC recognizes the need for effective internal processes, such as knowledge sharing and quality control, to ensure that Canadians receive the best possible service from the OPC.

Benefits for Canadians from Program Activity 3

By raising organizations’ awareness of their obligations under federal privacy laws and furnishing them with tools and information to better protect the personal information in their care, the OPC is helping to strengthen the privacy protections enjoyed by Canadians. The Office also directs communications and outreach activities specifically at individuals, thus heightening their awareness of their rights and abilities to exercise them. With a better understanding of the issues, Canadians are also better equipped to protect their personal information and reduce their privacy risks.

2.4 Program Activity 4: Internal Services

Activity Description

Internal Services are groups of related activities and resources that are administered to support the Office’s programs and other corporate obligations. As a small entity, the OPC’s internal services include two sub-activities: governance and management support, and resource management services (which also incorporate asset management services). Given the specific mandate of the OPC, communications services are not included in Internal Services but rather form part of Program Activity 3 – Public Outreach. Similarly, legal services are excluded from Internal Services at OPC, given the legislated requirement to pursue court action under the two federal privacy laws, as appropriate. Hence legal services form part of Program Activity 1 – Compliance Activities and Program Activity 2 – Research and Policy Development.

| 2010-2011 Financial resources ($000) | 2010-2011 Human resources (FTEs) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned Spending | Total Authorities | Actual Spending | Planned | Actual | Difference |

| 5,137 | 5,405 | 6,383 | 46 | 43 | (3) |

The actual spending includes reallocations between activities to better reflect Program activity spending.

| Expected Results | Performance Indicators/Targets | Actual Performance | Performance Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| The OPC achieves a standard of organizational excellence, and managers and staff apply sound business management practices. | Indicator: Ratings against the Management Accountability Framework (MAF) Target: Strong or acceptable rating on 70 percent of MAF areas of management |

As an Agent of Parliament, the OPC is not subject to a MAF assessment by Treasury Board Secretariat. Nonetheless, the Office conducts a comprehensive self-assessment exercise against the MAF biennially. In September 2010, the OPC completed its third self-assessment, which indicated an improvement in its management practices overall. In 2006-2007, 40 percent of MAF areas of management were rated ‘strong’ or ‘acceptable’; in 2008-2009, 60 percent reached that target and, in 2010-2011, 72 percent did. | Exceeded |

| Areas where OPC’s management practices met or exceed expectations were: Public Service values, utility of corporate performance framework, effectiveness of corporate management structure, quality and use of evaluation, quality of performance reporting, effectiveness of corporate risk management, excellence in people management, effectiveness of internal

audit function, effectiveness of IT management, effectiveness of procurement, effectiveness of financial management control, quality of TB submissions, and citizen-focused services. Three areas of management practices were rated as ‘opportunities for improvement’: investment planning, effectiveness of information management, and effective management of security. Work is underway to strengthen those areas with the development of an integrated investment plan that will substantiate resource allocation decisions; the creation of a governance structure to set priorities for business applications (e.g. current and future internal resource needs for the new case-management system); an update of the IM/IT strategic plan in line with the most pressing information management requirements; and the creation of a organizational security program to formalize the management of security. Two areas of management were rated as ‘attention required’ in the last self-assessment: managing organizational change, and effectiveness of asset management. To improve those areas, a formal change-management strategy was developed and all OPC initiatives involving significant change are now required to follow a road map for their smooth delivery. To improve on the management of assets, the OPC is developing a materiel management framework that will better support decision-making in this area. As well, the Office evaluated its space requirements, taking into account present and future needs and, partnering with the Office of the Information Commissioner, is negotiating with Public Works and Government Services Canada for a new joint location to move into in 2013 when the present accommodation agreement ends. |

Performance Analysis

In 2010-2011, the OPC conducted its third biennial MAF self-assessment exercise, with results indicating a steady improvement in management practices. Thirteen (13) of the 18 management areas assessed met or exceeded expectations of sound management, and the remaining five are currently being improved (see table above for detail). The OPC is also strengthening its management framework to better support its corporate priorities. Specifically, the OPC:

- implemented its 2008-2011 Integrated Business and Human Resources Plan, which effectively addressed employee orientation and specialized training; stabilized the workforce; led to increased use of social networking sites for recruiting; introduced new technologies to facilitate knowledge and information sharing; resulted in the development of policies and practices to support a healthy work environment and a talent-management program that includes succession planning activities;

- enhanced and broadened staff knowledge in specific areas through the use of developmental assignments both within and outside the Office;

- welcomed new resources through vehicles such as Interchange Canada;

- increased communication between the Inquiries unit and other branches of the Office to provide value-added intelligence about the nature and frequency of inquiries and to develop tools for individuals and organizations;

- rolled out SharePoint, an electronic collaboration tool, to all branches of the Office and provided mandatory training to all staff, in order to improve decision-making based on better sharing of information.

Lessons learned

Now that its workforce is stabilized, the Office faces the same challenge as many organizations: to maintain the momentum in a competitive and changing labour market. The Office is developing its 2011-2014 Integrated Business and Human Resources Plan, which will include the launch of a talent-management program in the first year of implementation.

The OPC experienced significant changes in recent years, including a major re-engineering of its inquiry and investigation functions from 2008 to 2010, a notable influx of new staff in 2009, the opening of a new office in Toronto in 2010, and an organizational restructuring at the end of 2010-2011. The Office will continue to evolve to further increase its effectiveness and better serve Canadians. A formal strategy for change management will be implemented in 2011-2012.

Section III: Supplementary Information

This section presents the financial highlights for 2010-2011 and a supplementary information table. Audited financial statements are available on the OPC website. More information about the OPC, such as statutory annual reports and other publications, may be found on the OPC website or by contacting the Office toll-free at 1-800-282-1376.

3.1 Financial Highlights

| % Change | 2010-2011 ($000) |

2009-2010 ($000) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Assets | 59% | 5,421 | 3,411 |

| Total Liabilities | 32% | 6,835 | 5,172 |

| Total Equity | 20% | (1,414) | (1,761) |

| Total | 59% | 5,421 | 3,411 |

| % Change | 2010-2011 ($000) |

2009-2010 ($000) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Expenses | .02% | 24,812 | 24,808 |

| Net Cost of Operations | .02% | 24,812 | 24,808 |

Total assets were $5.421M at the end of 2010-2011, an increase of $2.01M (59 percent) over the previous year’s total assets of $3.411M. Of the total assets, $3.004M (55 percent) was to be received from the Consolidated Revenue Fund. Tangible capital assets represented 31 percent of total assets, while accounts receivable and advances made up 12 percent and prepaid expenses, two percent of total assets.

Total liabilities were $6.835M at the end of 2010-2011, an increase of $1.663M (32 percent) over the previous year’s total liabilities of $5.172M. Accounts payable and accrued liabilities represented the largest portion of liabilities, at $3.392M, or 50 percent of the total. Employee severance benefits represented a slightly smaller portion of the total liabilities, at $2.65M, or 39 percent. Vacation pay and compensatory pay and accrued employee salaries accounted for seven percent and four percent of total liabilities, respectively.

Total expenses for the OPC were $24.812M in 2010-2011.The largest share of the funds, $11.131M, or 45 percent, was spent on compliance activities, while research and policy development represented $3.721M, or 15 percent, of total expenses. Public outreach efforts represented $3.612M of the expenditures, or 14 percent of the total. Internal Services accounted for the remainder of the expenditures, at $6.348M or 26 percent of the total.

Audited Financial Statements

Information on OPC's audited financial statements can be found at the following link: http://www.priv.gc.ca/information/an-av_e.cfm

3.2 Supplementary Information Tables

The OPC has a single supplementary table as follows:

Table 10 - Internal Audit and Evaluation

Approved internal audit and evaluation reports are available on the OPC website: http://www.priv.gc.ca/aboutUs/iac_e.cfm

[1] Reference is made to "individuals" in accordance with the legislation.

[2] The TBS scale for performance status refers to the proportion of the expected level of performance (as evidenced by the indicator and target or planned activities and outputs) for the priority or result identified in the corresponding Report on Plans and Priorities that was achieved during the fiscal year. The ratings are: exceeded – more than 100 percent; met all – 100 percent; mostly met – 80 to 99 percent; somewhat met – 60 to 79 percent; and not met – less than 60 percent.

[3] Type is defined as follows: previous – committed to in one of the past two Reports on Plans and Priorities (RPP) that correspond to this DPR; ongoing – committed to at least three fiscal years prior to the RPP that corresponds to this DPR; and new – newly committed to in the RPP that corresponds to this DPR.

[4] The data relating to PIPEDA files is for 12 months from January to December 2010 while the data for Privacy Act files is for 12 months from April 2010 to March 2011. With a redesign of the management information system currently underway, next year’s report will present all data on a fiscal year basis.

[5] The 2010-2011 Report on Plans and Priorities referred to this priority privacy issue as ‘national security’.

[6] Audit reports made public in 2010-2011 were: Audit of the Personal Information Disposal Practices in Selected Federal Institutions, Oct. 5, 2010; Audit of the Protection of Personal Information in Wireless Technology - An Examination of Selected Federal Institutions, Oct. 5, 2011; and Audit of Selected Mortgage Brokers, June 8, 2010.

[7] This performance indicator/target has been eliminated as it did not accurately reflect the OPC’s performance.

[8] The OPC is developing new service standards based on its re-engineered processes. The new standards will become the basis to report on the timeliness of responses-- i.e., the percentage of inquiries and complaints that are completed within the set service standards. This Departmental Performance Report presents actual turnaround times.

[9] The data relating to PIPEDA files is for 12 months from January to December 2010 while the data for Privacy Act files is for 12 months from April 2010 to March 2011.

[10] Targets are to be revisited once the OPC reaches full capacity.

[11] In addition to the published audits listed in footnote 6, three other audits were substantially completed during the fiscal year and were to be published after the end of the reporting period. They examined Staples Business Depot; privacy and aviation security, and selected RCMP operational databases.

[12] Audits followed up on in 2010-2011 focused on RCMP exempt databanks (2008), Canadian passport operations (2008), and the privacy management frameworks within selected federal institutions (2009).