Message from the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

I am pleased to present the Departmental Performance Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2011.

By pulling together our work under the Privacy Act and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, this report provides a unique overview of the past year. It reveals, among other things, the innovative ways in which we leveraged our resources for maximum impact, at home and abroad. For instance, we began the fiscal year by uniting with data protection authorities from nine nations to publicly challenge Google’s privacy practices. As the year went on, we linked up with domestic and international partners in data protection initiatives ranging from joint letters and resolutions to the development of online tools, the establishment of the Global Privacy Enforcement Network, and preparing for Canada’s new prohibition against unwanted electronic communications.

We also continued to focus on emerging challenges to privacy in four priority areas: public safety, information technology (IT), genetic information, and the protection of identity integrity. In IT, for instance, we dramatically bolstered our in-house expertise by recruiting specialized research analysts and establishing a dedicated IT test laboratory. We also published our findings in an audit of the government’s use of wireless networks and devices.

But, for all our forward focus, we tried never to lose sight of our founding mandate: to serve Canadians. We did that by strengthening our capacity to respond quickly and effectively to their inquiries and complaints. We also spoke to them where they live, work and learn, through outreach efforts, the creative use of social media, groundbreaking national consultations on online tracking, profiling and targeting and cloud computing, and regular interactions with the business community and the federal public service.

We reviewed Privacy Impact Assessments on numerous public safety measures and other government initiatives that matter to Canadians, and talked to Parliament about issues ranging from aviation safety and the long-form census to camera surveillance and open government. We also published an analytical framework for integrating privacy into public safety measures.

In October we opened an office in Toronto, where a significant number of Canadian businesses are headquartered. The new office is dedicated to strengthening compliance with privacy law among businesses in the region, further underscoring our commitment to serving Canadians.

Invariably, however, every achievement only whets the expectation for more. To meet such demand, we are retooling many of our processes. For instance, we now emphasize the early resolution of citizen complaints and focus our efforts on particularly complex or systemic issues. We have adopted a more systematic approach to the selection of privacy compliance audits, and have implemented mechanisms to strengthen our audit procedures. We have also developed a comprehensive document to help government officials understand our expectations for Privacy Impact Assessments.

Upon the three-year renewal of my term last December, I underlined that it is not enough to merely keep up with the changing privacy landscape; we must also anticipate and thoroughly understand developments, so as to better equip Canadians for the privacy challenges of tomorrow. This report describes the work of the past year that will help us meet that obligation.

The original version was signed by

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Section I: Overview

1.1 Summary Information

Raison d'être

The mandate of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada is to oversee compliance with both the Privacy Act, which covers the personal information-handling practices of federal government departments and agencies, and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), Canada's private-sector privacy law. The mission of the Office is to protect and promote the privacy rights of individuals[1].

Responsibilities

The Privacy Commissioner of Canada, Jennifer Stoddart, is an Agent of Parliament who reports directly to the House of Commons and the Senate. The Commissioner’s powers to further the privacy rights of Canadians include:

- investigating complaints, conducting audits and pursuing court action under two federal laws;

- publicly reporting on the personal information-handling practices of public- and private-sector organizations;

- supporting, undertaking and publishing research into privacy issues; and

- promoting public awareness and understanding of privacy issues.

The Commissioner works independently of other parts of the government to investigate complaints from individuals with respect to the federal public sector and the private sector. The focus is on mediation and conciliation, but if voluntary co-operation is not forthcoming, the Commissioner has the power to summon witnesses, administer oaths, and compel the production of evidence. In cases that remain unresolved, particularly under PIPEDA, the Commissioner may seek an order from the Federal Court to rectify the situation.

Strategic Outcome and Program Activity Architecture

In line with its mandate, the OPC pursues as its Strategic Outcome the protection of the privacy rights of individuals. Toward that end, the Office’s architecture of program activities is composed of three operational activities and one management activity. The PAA diagram below presents information at the program activity level:

| Strategic Outcome | The privacy rights of individuals are protected. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Program Activity | 1. Compliance Activities | 2. Research and Policy Development | 3. Public Outreach |

| 4. Internal Services | |||

Alignment of PAA to Government of Canada Outcomes

Federal departments are required to report on how their PAA aligns with Government of Canada Outcomes. The Privacy Commissioner, however, being independent from government and reporting directly to Parliament, is not obliged to make such alignment. The Strategic Outcome and the expected results from the work of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada are detailed in Section II of this Departmental Performance Report.

1.2 Performance Summary

The following table presents the OPC’s total financial and human resources for 2010-2011.

Financial and Human Resources

| * Funding for statutory obligations arising from the new anti-spam legislation, this was referred to in the 2010-2011 RPP as the Electronic Commerce Protection Act. | |||

| Planned Spending | Adjustment* | Total Authorities | Actual Spending |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23,239 | 974 | 24,213 | 22,824 |

| * Full-time Equivalents | ||||

| ** FTEs for statutory obligations arising from the new anti-spam legislation, this was referred to in the 2010-2011 RPP as the Electronic Commerce Protection Act. | ||||

| Planned | Actual | Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTEs | Adjustment** | Adjusted FTEs | ||

| 173 | 4 | 177 | 160 | (17) |

As of March 31, 2011, the Office had 160 employees. The variance of 17 FTEs is attributed in part to the late Royal Assent of the new anti-spam legislation where the staffing has been delayed and in part to a normal turnover rate of staff.

Contribution of Priorities to the Strategic Outcome

In 2010-2011, the OPC had five corporate priorities, which are listed in the table below. Work to advance each priority contributed to progress toward the Office’s Strategic Outcome. For each priority, the following table presents a summary of actual performance and a self-assessment of performance status, based on the Treasury Board Secretariat’s scale[2] of expectations. More detailed performance information is provided in Section II – Analysis by Program Activity.

| OPC Priorities for 2010-2011 | Type[3] | Performance Summary | Performance Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Redefine service delivery through innovation to maximize results | New |

The OPC created a robust intake unit to prioritize incoming complaints and allocate an appropriate level of resources for their effective resolution. As a result, concerned Canadians obtained faster responses to their complaints than in the past. Of the combined total of 899 complaint files closed in 2010-2011 (Privacy Act: 570, PIPEDA[4]: 329), 18 percent (Privacy Act: 78, PIPEDA: 80) were resolved quickly when the new intake unit applied early-resolution strategies. Because these cases did not require time-consuming formal investigations, they were closed on average in just 3.2 months. By comparison, cases that required formal investigations took an average of 11.8 months to close--eight months on average for Privacy Act complaints and 19.2 months for PIPEDA complaints. The Office worked with inter- and intra-departmental committees to prepare for the implementation of Canada's new anti-spam law, which was passed in December 2010. Frameworks are being devised to integrate the new powers allocated to the Commissioner as a result of this law. The OPC also worked with provincial and territorial counterparts on shared privacy issues, including:

The Office joined privacy enforcement agencies from around the world to establish the Global Privacy Enforcement Network (GPEN), a network designed to facilitate cross-border cooperation in the enforcement of privacy laws. |

Met all |

| 2. Provide leadership to advance four priority privacy issues (information technology, public safety[5] , identity integrity and protection, and genetic information) | Previous | In 2010-2011, the Office engaged in a variety of activities (publications, speeches, website content and media relations) to raise awareness of the four priority privacy issues among the public and other key stakeholders. The OPC published and distributed a new brochure about the four

priorities, to better explain what they are, why the OPC identified these priorities, and why others should be concerned about them as well. The OPC also undertook actions specific to each priority area in 2010-2011: Information technology: The OPC developed two fact sheets on protecting privacy on mobile devices, as well as an information document entitled, Data at Your Fingertips: Biometrics and the Challenges to Privacy. It also prepared several blog posts related to technical privacy issues, and organized industry briefings on a wide range of topics, such as biometrics, cloud computing, social network attacks, video surveillance and cyber security, significantly increasing the level of understanding of these issues within the organization and beyond. Public safety: The OPC developed a policy reference document: A Matter of Trust: Integrating Privacy and Public Safety in the 21st Century. This and related activities allowed the OPC to deepen its knowledge in the area, as reflected in speeches, analysis of crime bills, PIAs, appearances before Parliament, and other work. Identity integrity and protection: The OPC made a submission to the Digital Economy Consultation, led by Industry Canada. It also commissioned research on the public/private divide, identity management systems, privacy and developing countries, and the use of social media in government. The Office also created a speakers series to examine emerging privacy issues and commissioned papers from four speakers. Genetic information: The OPC commissioned the first part of a major research paper on the use of genetic information in the insurance context, prepared a draft fact sheet on direct-to-consumer sale of genetic testing services, and partnered with Genome Canada in a workshop series on genetic information called GPS – Where Genomics Public Policy and Society Meet. |

Met all |

| 3. Strategically advance global privacy protection for Canadians | Previous | This year, the Commissioner continued as Chair of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Volunteer Group on Privacy, mandated to assist the OECD in reviewing its Privacy Guidelines. The OPC provided staff to the OECD to help it mark the 30th anniversary of its Guidelines in advance of the review. The OPC was a founding member of the Global Privacy Enforcement Network and joined the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation (APEC) cross-border privacy enforcement initiative. The OPC continued to play a key role in the work of the International Standards Organisation (ISO) on identity management and privacy technologies. A member of the OPC sits on the Commission for the Control of INTERPOL’s Files. The OPC supported work on international resolutions that Canada sponsored, namely through involvement in the Accountability Project resulting from the 2009 International Data Protection Commissioners Conference in Madrid. The Office was also involved in activities of the Association francophone des autorités de protection des données personnelles, as well as in the Ibero-American Data Protection Forum. Throughout the year, the OPC received officials on fact-finding missions from foreign data protection authorities. The Office worked with other data protection authorities on common responses to global privacy concerns, such as the posting of personal information without consent during the launch of Google Buzz. The OPC also provided input to international organizations and associations prior to their launch of products and initiatives that could have an impact on privacy. |

Met all |

| 4. Support Canadians, organizations and institutions to make informed privacy choices | Previous | During 2010-2011, the OPC produced resource tools and organized outreach activities for several target audiences, including small-business owners, youth, and federal public servants. The Office expanded its outreach activities in Ontario through the opening of its Toronto regional office. As well, the Office launched a new speakers series titled Insights

on Privacy, and held public consultations in Toronto, Calgary and Montreal on privacy and online tracking, profiling and targeting, as well as cloud computing. The past year saw an increase in requests for OPC materials, visits to its website, and engagement through social media. The Office experimented with new methods to provide guidance and information to Canadians and organizations, including online video, interactive web tools, armchair discussions, and collaborative events. The OPC contributed to the international data protection community’s adoption of an international resolution on the importance of “Privacy by Design”. |

Met all |

| 5. Enhance and sustain the organizational capacity | Ongoing | The OPC continues to explore new approaches to recruitment and retention, such as through the use of social networking sites, and to expand the use of technology to develop knowledge-sharing tools. The Office participates in government-wide initiatives, including the move toward a more robust system for the management of human resources, the promotion of the Government of Canada Employee Passport approach, and the Common HR Business Processes. The effort to build more SharePoint sites within the Office has continued in 2010-2011, contributing to increased knowledge sharing, collaboration and synergy between organizational units. Several business processes were automated, particularly in the audit and the communications units, further facilitating the exchange of information and data. The OPC is now able to envisage the automation of its scorecard management tool, which has been maintained manually until now. The Office developed a long-term accommodation strategy by defining each organizational unit’s business requirements. The project was undertaken with Public Works and Government Services Canada, the entity charged with identifying an appropriate location for a move in 2013. |

Met all |

All commitments made to advance the five OPC corporate priorities in 2010-2011, as published in the 2010-2011 Report on Plans and Priorities, have been “met”.

Risk Analysis

External Factors

Canadians should be well aware that online risks and threats to personal information are very real. Digital information and systems are inherently vulnerable when interconnected and made globally accessible. Security problems, particularly cybercrime and cyber-espionage, are threatening our private and public e-infrastructures. A lack of industry standards undermines the security of services in the cloud. Service providers are taking advantage of the rapid product development opportunities, with privacy becoming an afterthought. Small and medium-sized businesses are using digital technologies without the education and tools needed to effectively safeguard personal information.

These threats are compounded by our ever-increasing reliance on online services and our propensity for sharing personal information. By embracing new technologies, Canadians of all ages, and youth in particular, are challenging and reshaping traditional notions of privacy. The effects on our society cannot easily be measured. The lines between our public and private selves are becoming blurred, particularly for our children, who are growing up in a digital world. Digital literacy programs that teach children and their parents to properly assess and mitigate online privacy risks are slowly gaining traction.

But, in the meantime, people’s online sharing behaviours continue to be a privacy concern. Individuals are not only using new forms of technology to communicate with each other, but also for everyday activities, such as banking and online shopping. Online financial transactions involve sensitive information, so the security and privacy of these transactions, particular when they are conducted from home computers and mobile devices, is essential to trust in the systems.

The global data protection community has recognized it needs to revisit and reaffirm first principles in the privacy arena. Too much time has now passed since first- (even second-) generation privacy laws and guidelines were arrived at in the 1970s for these to be resonant with younger citizens. A whole new generation of awareness around privacy, information ethics, data protection and online security needs to be re-launched, with citizens, schools, companies and government all playing a part.

Also clear is that advanced and ubiquitous digital surveillance and the global interception industry have grown enormously in the past decade. These technologies, when widely deployed, have a profound effect on civil liberties and human rights.

Governments are able to engage in the wholesale capture of individuals’ digital trail: SMS, text, geo-location, e-mail, to name just a few of the ways people can be tracked. The commercial potential, network capacity and technological scope for online monitoring have few remaining practical limits – aside from the law. Inexpensive bandwidth, expansive storage, ubiquitous devices and innocuous sensors are all driving the trend towards more surveillance and online tracking.

Faced with the shadow of cybercrime and the growth of cyber-surveillance, the risk is that trust may become the depleting resource of cyberspace.

Bandwidth and capacity were once the overriding technical preoccupations, but these have been supplanted by wider social issues of suspicion, surveillance and self-censorship. While there are no simple responses to these issues – whether they involve the mass screening of travellers or automated exchange of data across borders--a wide campaign of safeguards and solutions to these privacy risks is overdue. Government practices and laws must be adapted, commercial products and services better regulated, individual citizens better educated and empowered in the hopes they can secure their own data and online practices, and international standards agreed to, observed and enforced.

Personal information sharing on a mass scale represents a tectonic shift in social mores and behaviour. All networked societies are struggling to come to terms with the implications – in their companies and courtrooms, in their governments and global relations, in their schoolyards and studios. While the norms of social networking are slowly emerging, almost half of Canadians now use platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. These tools are dramatically changing the way people share information. Where people communicate, what they relate, when and why they share - all these are being reshaped by new channels, just as social networks have accelerated the transformation of personal information into a raw commodity for use by advertisers, data brokers, insurers and other commercial sectors.

Analytics—the use of new software tools to mine data for unexpected trends or patterns—have opened the door to unforeseen ethical considerations. As these technologies evolve, the contexts and definitions of “personal information” are also being revisited. Developments in geo-location, biometrics, genetics and online analytics call for a common understanding of the term and a return to basic privacy principles.

More broadly, protecting privacy in this rapidly transforming online landscape demands agile, creative and effective responses. Realistic guidance from regulators is increasingly important. Therefore, data protection authorities and other regulators are actively developing guidance and rules, in consultation with technological innovators, consumers and legal scholars and specialists. This trend reflects the global dimension of contemporary privacy issues. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission, the OPC and the European Union have all conducted consultations in the past year on data protection issues arising from a growing reliance on the Internet for communication, commerce and innovation.

Key Business Risks

Three areas were identified as critical risks in the 2010-2011 Report on Plans and Priorities and, as such, have been managed to mitigate their possible effects on the OPC. Two critical risks pertained to the OPC’s organizational capacity—in particular the capacity to address a high business demand for services, and to eliminate the long-standing backlog of investigation files. These risks were mitigated through a multi-pronged approach that included diligently allocating the additional funding received from Treasury Board to priority activities; applying an assortment of aggressive procedures to close backlogged files before March 31, 2010; employing innovative human resources management techniques to recruit, train and retain staff in a highly competitive market; and a major re-engineering project to streamline work processes, including the use of alternative interventions to respond to demands more efficiently. The Office continues to invest in streamlining its operations.

The third critical risk the Office was managing in 2010-2011 related to the protection of the OPC’s own data holdings against breaches, either due to system or human error. The OPC continues to manage this risk with due diligence. In 2010-2011, a threat and risk assessment was performed and corrective actions are being implemented. A business continuity plan developed in 2009-2010 was tested in 2010-2011 and will be reviewed again in 2011-2012. The testing of the plan led to the identification of some areas requiring attention, which are currently being addressed.

During 2010-2011, an organizational security program was prepared to outline new and existing security measures. Information about the secure handling of data was incorporated in the OPC employee orientation process. All staff participated in a security information session in November 2010 and will be expected to review, on an annual basis, the newly purchased computer-based training material on the OPC’s security and information-management needs.

Expenditure Profile

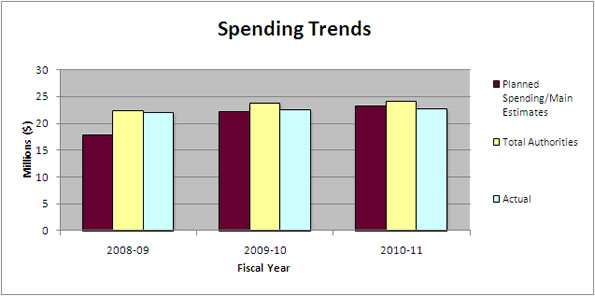

The OPC Main Estimates and Planned Spending amounts (presented as a single figure since there is no significant difference between the amounts) increased by $1.230 million from 2008-2009 to 2009-2010 following the approval of new funding from Business Case II. These funds were earmarked to address complaint investigations, expand public outreach, and implement a new internal audit initiative.

Many public outreach initiatives were directed at businesses and other target groups such as small businesses and youth. The OPC also now has an internal audit function. The increase between 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 spending authorities of $0.9 million is related to the passage into law of the new anti-spam legislation received in December 2010.

Voted and Statutory Items

For information on the OPC votes and statutory expenditures, refer to the 2010–2011 Public Accounts of Canada (Volume II).

- Date modified: