ARCHIVED - Canadian Human Rights Tribunal

This page has been archived.

This page has been archived.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

2006-2007

Departmental Performance Report

Canadian Human Rights Tribunal

Robert Douglas Nicholson

Minister of Justice

Table of Contents

Section I - Departmental Overview

Chairperson's Message

Management Representation Statement

Summary Information

Summary Information

Departmental Performance

Context

Section II - Analysis of Program Activities by Strategic Outcome

Analysis of Performance by Program Activity

Performance Accomplishments

The Effect of Recent Tribunal Decisions on Canadians

Section III - Supplementary Information

Organizational Information

Financial Statements

Response to Parliamentary Committees and Audits and Evaluations for Fiscal Year 2006-2007

Section IV - Other Items of Interest

Section I - Departmental Overview

Chairperson's Message

The number of complaints referred by the Canadian Human Rights Commission for inquiry by the Tribunal decreased slightly again in 2006 from the record highs we experienced in 2003 and 2004.

I remarked last year that one of the significant challenges facing the Tribunal was the number of parties appearing before us without legal representation. These complainants are often people of modest means who are not able to afford legal representation. To address this difficulty, the Tribunal implemented a new system of case management in 2005-2006.

At a very early stage in the inquiry process, a teleconference is conducted by a member of the Tribunal with all of the parties and/or their counsel. During the teleconference, the member explains the Tribunal's pre-hearing and hearing processes, and what is required from the parties. With agreement of the parties, the member also sets time frames for document and witness disclosure, as well as for hearing dates. In addition to explaining the Tribunal's hearing process, case management ensures that complaints are heard and decided within a timely period.

In 2006-2007, the Tribunal continued to make adjustments to its new case management process, its automated case management system, the Tribunal Toolkit, which was installed last year to enhance information retrieval efficiency and data integrity. We also completed a revision to the Tribunal's publication What Happens Next? Guide to the Tribunal Process, which is designed to help unrepresented parties better understand the Tribunal process.

The Tribunal remains well positioned to continue to offer Canadians a full, fair and timely hearing process.

J. Grant Sinclair

Management Representation Statement

I submit, for tabling in Parliament, the 2006-2007 Departmental Performance Report for the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal.

This document has been prepared based on the reporting principles contained in the Guide for the Preparation of Part III of the 2006-2007 Estimates: Reports on Plans and Priorities (RPP) and Departmental Performance Reports (DPR).

- It adheres to the specific reporting requirements outlined in the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat guidance;

- It is based on the department's approved Strategic Outcome and Program Activity Architecture that were approved by the Treasury Board;

- It presents consistent, comprehensive, balanced and reliable information;

- It provides a basis of accountability for the results achieved with the resources and authorities entrusted to it; and

- It reports finances based on approved numbers from the Estimates and the Public Accounts of Canada.

J. Grant Sinclair

Chairperson

Summary Information

Raison D'être

The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (the Tribunal) is a quasi-judicial body that hears complaints of discrimination referred by the Canadian Human Rights Commission (the Commission) and determines whether the activities complained of violate the Canadian Human Rights Act (CHRA). The purpose of the CHRA is to protect individuals from discrimination and to promote equal opportunity. The Tribunal also decides cases brought under the Employment Equity Act (EEA) and, pursuant to section 11 of the CHRA, determines allegations of wage disparity between men and women doing work of equal value in the same establishment.

Total Financial Resources in 2006–2007 (Millions of Dollars)

|

Planned Spending |

Total Authorities |

Actual Spending |

|

4.3 |

4.6 |

4.6 |

Total Human Resources in 2006–2007

|

Planned |

Actual |

Difference |

|

26 |

26 |

- |

Departmental Priorities: Program Activity: Public Hearings under the Canadian Human Rights

|

Strategic Outcome: Canadians have equal access to the opportunities that exist in our society through the fair and equitable adjudication of human rights cases that are brought before the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal. |

||||

|

Alignment to Government of Canada outcomes: inclusive society that promotes linguistic duality and diversity. |

||||

|

|

2006-2007 |

|||

|

Priority No. and Type |

Expected Result |

Performance Status |

Planned Spending |

Actual Spending |

|

1. Monitor Tribunal inquiry performance targets. |

Performance measures confirmed. Efficiency of the inquiry process. |

met, ongoing |

N/A |

N/A |

|

2. Results-based Management Accountability Framework (RMAF). |

The Tribunal has developed its RMAF and is monitoring Modern Comptrollership practices. |

partially met, ongoing |

$25,000 |

N/A |

|

3. Management Accountability Framework assessment. |

Modern public service management that fully supports results for Canadians. |

new, ongoing |

$15,000 |

N/A |

|

4. Align Tribunal's record management systems with government information management policy. |

Implementation of the government standard Records, Documents and Information Management System (RDIMS). |

The RDIMS was implemented within the timelines established. |

$25,000 |

$6,000 |

Departmental Performance

The Tribunal's mission is to better ensure that Canadians have equal access to the opportunities that exist in our society through fair and equitable adjudication of the human rights cases brought before it. Pursuit of that goal requires the Tribunal to determine human rights disputes in a timely, well-reasoned manner that is consistent with the law.

During fiscal year 2006-2007, the Tribunal's workload continued to be extremely heavy. Although the volume of new complaint referrals continued to ease through 2005 and 2006, the combined average of cases received since 2003 represents a 145% increase over the Tribunal's previous seven-year average of 44.7 cases per year (see Table 1). In addition, the evidence and issues raised in complaints continue to be increasingly more complex than in the past. These are factors that play heavily on the timelines targeted by the Tribunal for conducting inquiries into complaints. Despite these pressures, the Tribunal's performance during the period under review remained very productive, both from the perspective of an efficient inquiry process and from the viewpoint of fair and impartial disposition of complaints.

Table 1. New Cases, 1996 to 2006*

|

|

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

Totals |

|

Human Rights Tribunals/ Panels |

15 |

23 |

22 |

37 |

70 |

83 |

55 |

130 |

139 |

99 |

70 |

743 |

|

Employment Equity Review Tribunals appointed |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

|

Totals |

15 |

23 |

22 |

37 |

74 |

87 |

55 |

130 |

139 |

99 |

70 |

751 |

|

* Pursuant to the Canadian Human Rights Act, complaints before the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal are referred by the Canadian Human Rights Commission. |

||||||||||||

The Tribunal rendered a total of 59 decisions and 129 rulings during the period from 2003 through 2006. In 2006 alone, the Tribunal released 13 decisions and 44 rulings.

In 2004-2005, the Tribunal re-examined its inquiry procedures when it adapted its active case management model to the way in which the inquiry process was conducted. That model, now referenced in the Tribunal's What Happens Next? guide, was implemented during 2005-2006 and revised in 2006-2007. Our experience to-date suggests that both the parties and the Tribunal benefit greatly from this new approach, with fewer procedural disputes at hearing and greater efficiency in the presentation of evidence and witnesses. Anecdotal evidence continues to suggest that this new approach is engendering savings to both the parties and the Tribunal by streamlining hearings that would otherwise be much longer.

In cases where the parties are inclined to resolve complaints without a full hearing, the Tribunal offers a one-day mediation, where its experienced members meet with the parties. As mediations are completely voluntary, the resulting settlements translate into concrete results for all parties concerned, at a reduced cost. In fiscal year 2006-2007, 27 of the 39 mediations conducted by Tribunal members resulted in settlements. In cases where a mediated settlement cannot be reached, or mediation is declined by the parties, the Tribunal's new case management approach ensures the continuation of the inquiry process without delay, and that the parties are afforded timely access to the Tribunal's adjudicative process.

Operational Environment

Hearings before the Tribunal are more adversarial, with motions and objections ever more frequent. Although the Tribunal has developed pre-hearing disclosure procedures to ensure fair and orderly hearings, their efficiency is compromised by missed deadlines, requests for adjournments and vehemently contested issues. Hearings on the merits are longer and increasingly complex and parties appear uncertain of how to focus on the specific issues requiring determination. In such instances, the Tribunal intervenes by conducting case management conferences, which allow the Tribunal to guide the parties toward an approach that is predictable, streamlined and fair, thus ensuring hearings that are consistent with the expeditious process contemplated by the CHRA.

Faced with its highest-ever volume of new complaints during the three calendar years of 2003 through 2005, and given the complexities described above, the Tribunal cannot reasonably expect that all cases can be completed within its 12-month target period. However, based on procedural adjustments made in 2003-2004 and given the active case management practices initiated in 2005-2006, the Tribunal remains optimistic of its ability to minimize the impact of delays where the 12-month target is concerned. While the Tribunal is careful not to exert undue pressure on the parties when imposing constraints, it acknowledges that a more proactive approach to case management will continue to benefit the parties through a balanced and efficient use of available resources.

Context

Jurisdiction

The Canadian Human Rights Act (CHRA) applies to federal government departments and agencies, Crown corporations, chartered banks, railways, airlines, telecommunicationsand broadcasting organizations, as well as shipping and inter-provincial transportation companies. Complaints may relate to discrimination in employment or in the provision of goods, services, facilities and accommodation that are customarily available to the public. The CHRA prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, age, sex, marital status, family status, sexual orientation, disability or conviction for which a pardon has been granted. Complaints of discrimination based on sex include allegations of wage disparity between men and women doing work of equal value in the same establishment.

In 1996, the Tribunal's responsibilities were expanded to include the adjudication of complaints under the Employment Equity Act (EEA), which applies to all federal government departments and federally-regulated private sector employers with more than 100 employees. Employment Equity Review Tribunals are created, as needed, with members of the Tribunal, and usually relate to the review of a direction given by the Canadian Human Rights Commission to an employer with respect to an employment equity plan. After hearing evidence and arguments, the Tribunal may confirm, rescind or amend the Commission's direction. Since the first such Tribunal in February 2000, only seven other applications have been made, since 2002-2003 (see Table 1). To date the parties have reached a settlement before hearing has commenced in all cases.

Parliament's passage of amendments to the CHRA in 1998 provided for a more highly qualified Tribunal, which we believe is generating a more consistent body of jurisprudence through its decisions and written rulings. In the years since the amendments were passed, we continue to perceive a greater acceptance of the Tribunal's interpretation of the CHRA by the reviewing courts. This development is expanded upon in Section II of this report (see Table 3). Eventually, this acceptance will benefit both complainants and respondents, and will ultimately result in more timely, fair and equitable disposition of complaints, at a reduced cost to Canadians.

Risk Management Issues

As noted in previous departmental performance reports, the Tribunal continues to face risks in the following major areas: workload and the increasing number of unrepresented parties. A brief synopsis of these risks and what the Tribunal has done to address them follows.

The number of complaints referred to the Tribunal has risen dramatically since 2002, when only 55 cases were received. In 2003, 130 new complaint cases were referred and, in 2004, that number rose again to 139 cases. The volume of complaint referrals dropped slightly to 99 in 2005, and 70 in 2006, but this volume of referrals remains significantly higher than the annual average of 44.7 cases received by the Tribunal from 1996 through 2002.

In addition to the high volume of complaints, the Tribunal is also faced with the challenge of conducting an adjudicative process in which many complainants are not represented by legal counsel. The Canadian Human Rights Commission's participation at hearings, while helpful to all parties, has reduced considerably since 2004. As such complainants without representation often conduct their cases and lead evidence by calling witnesses to prove allegations with limited legal guidance – requiring Tribunal members and staff to spend considerable time explaining the mediation and inquiry processes. These cases generally require additional case management at the pre- hearing stage to ensure that fairness is not jeopardized.

The Tribunal has made several changes in response to these circumstances. The practice of mediation was reintroduced in March 2003, despite their having been discontinued for reasons that are still relevant, as explained in past reports. The Tribunal also adjusted operating procedures to better meet the needs of unrepresented parties; revised initial correspondence to the parties to ensure better understanding of the information required to process a complaint; and adopted a more active approach to keep the process on track and to ensure parties meet deadlines.

Although procedures continue to be adjusted, the large increase in workload combined with the challenges of dealing with unrepresented parties places considerable stress on the Tribunal's ability to meet its targeted timeframes for concluding complaint inquiries. While the delays are not excessive, in the majority of cases the Tribunal considers any decline in service to our clients to be unacceptable. The Tribunal continues to monitor its workload and procedures closely, and is making adjustments where necessary to ensure that the quality of its services is not compromised.

Section II - Analysis of Program Activities by Strategic Outcome

Analysis of Performance by Program Activity

The Tribunal's two program activities, described below, together with its management and corporate administration activities, achieve the strategic outcomes and results for Canadians as shown in the logic model (Figure 1).

Program Activity: Public Hearings Under the Canadian Human Rights Act

Financial Resources (Millions of Dollars)

|

Planned Spending |

Authorities |

Actual Spending |

|

4.3 |

4.6 |

4.6 |

Human Resources

|

Planned |

Authorities |

Actual |

|

26 |

26 |

26 |

Description

Inquire into complaints of discrimination to decide if specific practices contravene the Canadian Human Rights Act.

Results

Clear and fair interpretation of the Canadian Human Rights Act; an adjudication process that is efficient, equitable and fair to all who appear before the Tribunal; and meaningful legal precedents for the use of employers, service providers and Canadians.

This program activity actions all the priorities identified in Section 1.

Performance Indicators

|

Client satisfaction Serving Canadians Number of cases commenced, pending, completed, withdrawn/discontinued, by time lines Number of cases heard/decided/settled Number of judicial reviews (overturned/upheld) |

Program Activity: Review Directions Given Under the Employment Equity Act

Financial Resources (Millions of Dollars)

|

Planned Spending |

Authorities |

Actual Spending |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

Human Resources

|

Planned |

Authorities |

Actual |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

Description

Conduct hearings into: requests from employers to review directions issued to them by the Canadian Human Rights Commission (the Commission); or applications from the Commission to confirm directions given to employers.

Results

Clear and fair interpretation of the Employment Equity Act; an adjudication process that is efficient, equitable and fair to all who appear before the Tribunal; and, meaningful legal precedents for the use of employers, service providers and Canadians.

No activity occurred for this program activity during the period covered by this performance document.

Figure 1 Logic model

|

Key Results |

|

|

1. Timely and well-reasoned determinations of human rights disputes referred by the CHRC under the Canadian Human Rights Act, as well as matters heard under the Employment Equity Act, that are consistent with both the evidence and the law. |

2. Efficient and expedient registry and administrative services that fully and effectively meet the needs of tribunal members in conducting human rights and employment equity inquiries, and the needs of the parties that appear before them. |

|

LONG-TERM OUTCOMES |

|

En application de la Loi canadienne sur les droits de la personne et de la Loi sur l'équité en matière d'emploi, les individus bénéficient d'un accès équitable aux possibilités qui existent au sein de la société canadienne grâce au traitement juste et équitable des causes relatives aux droits de la personne et à l'équité en matière d'emploi qui sont renvoyées devant le Tribunal canadien des droits de la personne |

|

IMMEDIATE & INTERMEDIATE OUTCOMES |

|||||

|

Quality Service |

Compliance |

Awareness |

Fairness |

Credibility |

Accessibility |

|

OUTPUTS |

||||

|

Orientation |

Liaison |

Policy and Procedures |

Information Sharing |

Liaison |

|

ACTIVITIES |

||||

|

Awareness/ Education |

Case Management |

Contract and Procurement |

Information, Tools, and Communications |

Reception Human Resources Management |

|

Canadian Human Rights Tribunal |

||||

Summary of Results Achieved

The Tribunal's primary purpose is to conduct hearings and render decisions. The followingis an overview of 14[1] final decisions that were rendered in 2006–2007, four of which are profiled in greater detail on page 26.

The Tribunal rendered five decisions regarding complaints filed under s. 13 of the CHRA. Section 13 makes it a discriminatory practice to telephonically communicate hate messages based on a prohibited ground of discrimination. All five cases involved communication over the Internet, and in each case the complaint was substantiated.

The Tribunal rendered two decisions involving employees of the Canadian National Railway. In one case, the complainant was seeking accommodation of his disability, epilepsy. In the second, the complainant sought accommodation of her pregnancy and family obligations. Both complaints were substantiated.

Two cases were also filed against First Nations councils. In one case, the complainant unsuccessfully alleged discrimination in connection with the calculation of her maternity leave top-up benefit. In the other, the Tribunal found that the respondent failed to accommodate the complainant upon return to work following cancer treatment. However, a separate allegation of retaliation by that First Nation for filing the complaint was dismissed.

A complaint against Canada Post regarding accommodation of a disability resulted in a divided ruling. While the employer was entitled to seek out certain medical information regarding the complainant's capacity to do her job, other aspects of the disability management process were found to be discriminatory.

A decision with respect to the National Capital Commission's duty to accommodate a wheelchair user in the design of a public stairway gave the Tribunal the opportunity to address the issue of access to services or facilities customarily available to the public.

Accommodation of disabilities was also at issue in a decision involving the administration of the Canadian Forces' health care plan. In this case the complainant, a member of the Canadian Forces, was denied funding for a fertility treatment.

Finally, the Tribunal dismissed two complaints filed against banks: an age discrimination complaint filed against the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce in connection with employee downsizing and pension eligibility, as well as a gender discrimination complaint filed against the Royal Bank of Canada regarding pension buy-back eligibility rules.

1The term « final decision » as used here connotes only those decisions that dealt with the question of whether discrimination occurred, that is to say, decisions on the merits of the complaint. Excluded therefrom are interim decisions and rulings that dealt solely with procedural, evidentiary or remedial issues.

Key Activities

To achieve its strategic outcome, the Tribunal must perform the following key activities:

- It must manage the Tribunal's workload.

- It must provide efficient and effective coordination of complaint cases.

Tribunal's Workload

The Tribunal experienced its highest-ever workload during the period from 2003 through 2005. Although the volume of complaint referrals began to ease in 2005 and 2006, the combined average of cases received during the three years from 2003 through 2005 represents a 145% increase over the Tribunal's previous seven-year average of 44.7 cases per year (see Table 1). Also, in addition to the high number of litigants appearing at hearings without expert legal representation, the preliminary and substantive issues requiring rulings or decisions are increasingly complex, as the nature of human rights in the modern Canadian environment rapidly evolves.

A question often arises as to how closely an adjudicating body should manage the adjudication process to ensure its efficiency. While much depends on the nature of each particular case, the dramatic increase in the workload in recent years has meant that active management of complaint cases before the Tribunal is necessary to avoid delays and minimize additional costs.

This is particularly important for cases where parties are less familiar with the adjudication process and without legal representation, as time invested in case management can engender savings at hearing – minimizing the potential for debates that are irrelevant to the key points for decision.

Case Coordination

As a small organization, the Tribunal must maximize its limited resources to meet the challenge of its current workload. This requires the coordination of mediations and hearings, the pre-hearing process, potential hearings to decide preliminary issues, as well as case management conferences, for cases where mediation is either declined or unsuccessful.

The Tribunal's Registry closely monitors the deadlines for parties to meet their pre-hearing obligations, such as disclosure, identification of witnesses and facts, and submissions on preliminary issues.

From one office in the National Capital Region, the Tribunal's efficiency and effectiveness is challenged when conducting multi-party conferences and hearings at locations across Canada.

In 2006-2007, the Tribunal's Registry enhanced its operational processes, including the manner and nature of its communications with parties, without change to the Tribunal's case management system.

The Tribunal also continues to investigate opportunities for technological advancements, following the successful standardization and harmonization of its computer systems in 2006-2007. An Intranet Committee was initiated to assist in the design of a more effective operational communication tool, and the Tribunal's Information Technology section also completed research into Digital Voice Recording, which will replace the need for stenographic services at Tribunal hearings as of July 2007. These initiatives will create efficiencies within the Tribunal, while realizing considerable cost savings.

Performance Accomplishments

1. Monitoring of Inquiry Performance Targets

|

Planned Activities |

Results Achieved |

|

Monitor the Tribunal's case management initiative and, if appropriate, adjust measures. |

Measures confirmed as adequate, although requiring further monitoring. |

The Tribunal has identified three leading performance measurement targets for ensuring the timely and effective delivery of its hearing process to clients:

- Commence hearing within six months of receiving the case referral, in 80% of cases;

- Render decisions within four months of the close of the hearing, in 95% of cases; and

- Conclude cases within 12 months of referral.

These targets were reviewed in 2004-2005 through an exercise to develop a Results-based Management and Accountability Framework for the Tribunal. Although the Tribunal's heavy workload has stressed the limits of these measures, we believe they are still relevant for the purpose of evaluating the Tribunal's performance.

Achieving these targets in 2006-2007 proved difficult, due to delays requested by the parties; the complexity of the complaints themselves; and the record high number of complaint referrals to be addressed, despite the easing number of new referrals (see Table 1). Although workload continues to impact the Tribunal's ability to render decisions within its targeted timeframe, delays requested by the parties remain the primary factor affecting the Tribunal's ability to fully meet these targets.

- In 2003-2004, of the 28 cases requiring a hearing, only 12 (42.9%) commenced within a six-month timeframe. The greatest delays were incurred during the earliest period of the transition to the Tribunal's new procedures, which were revised in response to increased workload and changes to the extent of the Commission's participation in inquiries. In 2004-2005, only four (26.7%) of the 15 cases began hearings within the six-month timeframe. In 2005-2006, three (33%) of the nine cases requiring a hearing began within six months. In 2006-2007, none of the 25 cases requiring a hearing began within the six-month target.

- In 2003-2004, 62% of the 16 decisions rendered by the Tribunal were released within four months. Although that target decreased to 54% of the 13 decisions released in 2004-2005, only three decisions took longer than six months, and the average time for release of decisions was only marginally above the four-month target. In marked contrast to the two previous fiscal periods, only 27% of the 12 decisions in 2005-2006 were rendered within the Tribunal's four-month target. This measure saw some improvement in 2006-2007, with 33% of 15 decisions rendered within four months. As three decisions only marginally surpassed the four-month target, 53% were rendered within, or close to, the Tribunal's stated target. In fact, the average time for completion of all 15 decisions last fiscal year was slightly above five months.

- As indicated in Table 2, the average number of days to complete cases in 2002 and 2003 was 214 and 187 days, respectively. This average rose to 199 days in 2004, 209 days in 2005 and 275 days in 2006. The apparent anomaly of a shorter average to close files, as compared to the longer average to first day of hearing, results from the high number of settlements occurring either through mediation or between the parties on their own. For cases requiring a full hearing and decision, the average time to close a case in 2001 was 384 days, with six cases requiring more than one year to finalize. In 2002, this average was reduced to 272 days, none of which exceeded the one-year timeframe. In 2003, the average was 405 days, with eight cases requiring more than one year to complete. Although that average improved slightly to 396 days in 2004, 11 of the total 18 cases exceeded the one-year timeframe. In 2005 and 2006, however, the average to close files after hearing and decision rose to 458 and 427 days, respectively. No cases following a hearing and decision in 2006 were within 12 months of referral from the Commission.

Table 2. Average Days to Complete Cases, 1996 to 2006, from Date of Referral from the Canadian Human Rights Commission

|

|

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

*2006 |

|

To first day of hearing |

234 |

93 |

280 |

73 |

213 |

293 |

257 |

190 |

297 |

350 |

306 |

|

Time for decision to be submitted from close of hearing |

189 |

75 |

103 |

128 |

164 |

177 |

158 |

126 |

129 |

148 |

136 |

|

Average processing time to close file |

266 |

260 |

252 |

272 |

272 |

255 |

214 |

187 |

199 |

211 |

132 |

|

*As at report date, many complaints referred in 2006 are still at the pre-hearing case management stage or otherwise remain open due to delays from the parties. Figures with respect to complaints referred in 2006 are therefore subject to change. |

|||||||||||

Although the case completion targets established by the Tribunal have not been met during the period under review, we are confident that the case management model involving a member during the pre-hearing phase meets the needs of the parties, while reducing costs. Early case management involvement appears to help avert disagreements that might otherwise create a logjam. For example, in 1994, the Tribunal rendered 16 decisions on the merits of discrimination complaints and issued only 24 rulings (with reasons) dealing with procedural, evidentiary, jurisdictional or remedial issues. In 2005, 11 decisions on the merits and 37 rulings were rendered. In 2006, the number of rulings climbed to 44, with 13 decisions on the merits.

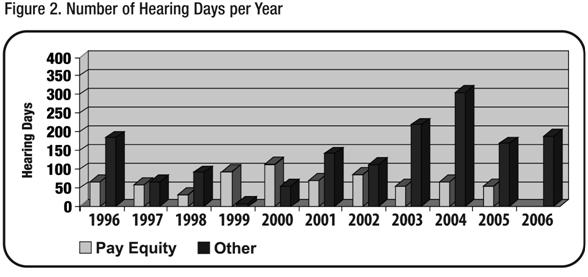

Whether or not this latest trend is wholly or partially attributable to case management is difficult to say. As remarked earlier in this report, complaints brought before the Tribunal have become increasingly complex. It is noteworthy, however, that the number of hearing days in 2005 decreased dramatically from the steady incline experienced over the preceding five years (see Figure 2). Rather, as many case management teleconferences between a Tribunal member and the parties occurred in 2005 as were total days spent at hearings.

Case management as a formal process remains relatively new at the Tribunal, and is expected to result in a more efficient hearing process that will incur savings for all involved. As parties become better acquainted with the Tribunal's active case management approach, it is expected that the cases will move more quickly through the system.

2. Results-Based Management and Accountability Framework (RMAF)

|

Planned Activities |

Results Achieved |

|

Continue development of the Tribunal's Results-Based Management and Accountability Framework (RMAF). |

The Tribunal has implemented its RMAF, assessed and adjusted performance measurement mechanisms, and continues to monitor its Modern Comptrollership practices. |

In our 2006-2007 Report on Plans and Priorities, we stated that a consultant would be hired to assist us in assessing the effectiveness of the Tribunal's RMAF. This activity is on hold until the framework for implementing the Treasury Board of Canada's new evaluation policy for small departments and agencies, a project involving the Tribunal's management team, is finalized. Also, in order to comply with new requirements for the Treasury Board of Canada's Management, Resources and Results Structure (MRRS) issued in 2006-2007, we made changes to our Program Activity Architecture (PAA), to take effect in 2008-2009. This may require a complete review of our entire performance framework, including indicators, targets and data sources. Since the RMAF, evaluation framework, PAA and MRRS are inter-related, the performance management framework will be revised as necessary in 2007-2008.

3. Management Accountability Framework (MAF) Assessment

|

Planned Activities |

Results Achieved |

|

Review management practices at the Tribunal for their adequacy in supporting its mandate and integrate human resource planning into the Tribunal's business plan framework. |

Management Accountability Framework (MAF) assessment completed by Treasury Board of Canada, Secretariat and recommendations being implemented where appropriate. |

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat assessed the Tribunal's Management Accountability Framework (MAF) in 2006-2007. At this time, the results of the assessment have not yet been released to the public. Areas identified by the Treasury Board of Canada, Secretariat as requiring improvement will be addressed and acted upon in a most timely manner.

The Tribunal participates in the Small Departments and Agencies (SDA) advisory committee to the Office of the Comptroller General of Canada (OCG) regarding the development of a plan for implementation of the Treasury Board's Internal Audit Policy within the SDA community. In 2006-2007, the Office of the Comptroller General of Canada audited the travel and hospitality of SDAs. The Tribunal provided preliminary information to OCG staff, but was not among the group of SDAs chosen for the audit. The Tribunal will, nevertheless, watch closely for the results of the audit and will review the resulting recommendations as may apply to Tribunal procedures and processes.

The Tribunal has also been engaged in consultations with representatives of the Treasury Board of Canada, Secretariat on the development of a plan for implementation of the Treasury Board's evaluation policy within the SDA community. The Tribunal will continue to monitor risks to determine the need for additional internal audits, or the need for evaluation, until these implementation plans for SDAs are finalized.

In 2006-2007, work was initiated regarding the Tribunal's business continuity plan and compliance with Management of Information Technology Security (MITS) standards,as directed by the Treasury Board of Canada, Secretariat. Both are slated for completion in 2007-2008. The Tribunal also continued the ongoing review of management practices and policies to ensure their soundness and relevance in supporting Modern Comptrollership, Human Resources Management Modernization, Service Improvement and Government-On-Line. This includes steps taken to ensure that the Tribunal's human resources plan is relevant to its business plan, while reflecting public service values. The Tribunal also reviewed its information and decision-making practices, and established effective mechanisms for decision recording, transparency and for the development of terms of reference for the organization's management committees.

The Tribunal also conducted a review of its communication tools to foster recognition and use of both of the official languages. The Tribunal's What Happens Next? pamphlet has been revised and republished, our Internet site has been reviewed and enhanced, and modernization of the Tribunal's Intranet has been initiated.

4. Alignment of Management Systems with Government Information Management Policy

|

Planned Activities |

Results Achieved |

|

Develop and implement in the Tribunal the government-wide Records Documents and Information Management System (RDIMS). |

Records, Document and Information Management System (RDIMS) successfully implemented. |

In 2006-2007, the Tribunal successfully implemented the Records, Document and Information Management System (RDIMS) for the management of its corporate records. This is part of the organization's information classification and retrieval process, which sustains business delivery improvement, legal and policy compliance, citizen access to information and accountability. By implementing this system, the Tribunal enhanced its Framework for Management of Information (FMI) compliance, and developed various policies and guidelines relating to information management aligned with the FMI. The RDIMS application is also planned for eventual integration with the Tribunal's automated case management database, the Tribunal Toolkit, by 2008-2009. This will further enhance information retrieval efficiencies and strengthen the Tribunal's strategy for ensuring data integrity and business continuity.

The last fiscal year saw the implementation of an action plan to meet the government's Management of Information Technology Security (MITS) and approval of a departmental information technology security policy. Identification of assets was completed, as well as a threat risk analysis of the Tribunal's infrastructure. Certification and accreditation for the infrastructure will be completed by fall of 2007, following completion of a vulnerability assessment. In 2006-2007, the Tribunal also completed and approved a business continuity plan to be tested later in 2007.

Security has been reinforced through awareness sessions provided by the RCMP. A new employee orientation guide that includes security awareness information has also been developed.

A vulnerability assessment and certification of the Tribunal's infrastructure and an external audit are among the activities planned for 2007-2008.

The Effect of Recent Tribunal Decisions on Canadians

The mission of the Tribunal is to provide Canadians with a fair and efficient public inquiry process for the enforcement of the Canadian Human Rights Act (CHRA) and the Employment Equity Act (EEA).

The Tribunal's single program is to conduct hearings, with its principal goal to do so as expeditiously as possible, while rendering fair and impartial decisions that will withstand the scrutiny of the parties involved and the courts that review the decisions. In other words, whatever the result of a particular case, all parties should feel that they were treated with respect and fairness.

In 2006–2007, the Tribunal issued 14 final decisions with reasons that answered the question, "Did discrimination occur in this case?"Tribunal decisions put an end to disputes between complainants and respondents as to whether the CHRA was infringed in a particular instance (subject to rights of judicial review before the Federal Court). These decisions also have an impact beyond the parties, bringing real benefits to Canadian society as a whole.

Simply put, Tribunal decisions give concrete and tangible meaning to an abstract set of legal norms. The CHRA prohibits discriminatory practices. It also offers justifications for certain conduct that may be discriminatory, but it does not give examples or illustrations. For that matter, the CHRA does not define the term discrimination. It is primarily through Tribunal decisions that Canadians can learn of the extent of their rights and obligations under the legislation. As such, a decision dismissing a complaint is just as noteworthy as a decision that finds a complaint to have been substantiated.

The following are summaries of four decisions rendered by the Tribunal in 2006-2007. They offer a glimpse into the kinds of complaints brought before the Tribunal, as well as insight into how such cases affect all Canadians. Summaries of other Tribunal decisions rendered in 2006 can be found in the Tribunal's 2006 annual report.

Brown v. National Capital Commission and Public Works and Government Services Canada 2006 CHRT 26 – Judicial review pending.

The complainant, Mr. Brown, alleged that the respondent, the National Capital Commission (NCC), discriminated against him by denying him "access to services by failing to accommodate [his] disability (wheelchair user), contrary to section 5 of the CHRA." The discrimination was alleged to be ongoing. In question were the steps located at the intersection of York Street and Sussex Drive in Ottawa. Mr. Brown alleged that they are not wheelchair accessible, and the Canadian Human Rights Commission joined him in arguing that persons who could not climb the steps had no way of traversing Sussex Drive at the bottom of the stairs to Mackenzie Avenue at the top.

The Tribunal found that the NCC was legally obliged to provide accommodation to the point of undue hardship in the immediate vicinity of the steps. The elevator access that was offered for those who could not climb the steps was not sufficiently near the site to constitute acceptable accommodation; it required disabled persons to make a detour that others did not. Moreover, the duty to accommodate included an obligation to participate in a meaningful dialogue with the parties requiring accommodation – to make inquiries and consult with the other parties including the complainant – and to continue consulting, until all reasonable accommodation alternatives were exhausted. The Tribunal also found that there was a reciprocal duty on the part of the complainant to participate in such consultations in good faith and to accept a reasonable offer of accommodation. It is impossible to know where a collaborative, open-ended round of consultations might have led since it never came to pass.

The Tribunal found that the NCC had a duty to make the York Street steps accessible, up to the point set out in the CHRA, including an obligation to investigate the possibility of using an adjacent building as a venue for an elevator. The adjacent building is owned by Public Works and Government Services Canada, a department that, along with the NCC, has an obligation to cooperate in the investigation as well as participate in the consultations, since both federal government organizations are emanations of the Crown. The Tribunal found that both respondents failed in their obligations.

Given the legal mandate of the NCC, the Tribunal also found that in determining undue hardship, in this case the duty to accommodate should be informed by the need to respect architectural and aesthetic values at a particular site. The parties were ordered to engage in a new process of consultation and accommodation in accordance with the decision.

| Results for Canadians |

|

While many of the complaints decided by the Tribunal deal with employment issues, the application of the Canadian Human Rights Act is not limited to employment matters. In particular, s. 5 of the CHRA addresses access to services and facilities customarily available to general public. The issue of disabled persons' access to public services and facilities is an extremely important one, and presents several conceptual and logistical challenges that do not arise in employment cases. Thus far, the Tribunal has not had many opportunities to explore this facet of the CHRA in the context of alleged structural or architectural barriers. The Brown decision is a significant contribution to this area of the law, and provides Canadians with important guidance on the rights and obligations surrounding the accessibility of public facilities. |

Buffet v. Canadian Forces 2006 CHRT 39 – Judicial review pending.

The complainant alleged that the Canadian Forces (CF) denied him an employment benefit by refusing to grant him funding for a reproductive medical procedure (in vitro fertilization). He claimed that this refusal constituted adverse differential treatment based on his disability (male factor infertility), his sex and his family status, in breach of s. 7 of the CHRA. He also alleged that the CF's funding policy regarding reproductive medical procedures was discriminatory, contrary to s. 10 of the CHRA.

The Tribunal found that Mr. Buffett's complaint was substantiated. The CF's health care policy provides a publicly funded service to infertile female members, if involving the participation of their male partners, CF members or otherwise. On the other hand, the CF will not provide this benefit to a male member with infertility problems on the grounds that the procedure involving his female partner is much more medically complex. In both situations, participation of each a male and a female partner is required. Not only is the CF policy discriminatory, evidence to establish that the CF would have incurred undue hardship by accommodating Mr. Buffett and other male CF members with male factor infertility was insufficient. The Tribunal found that the cost of accommodation, as estimated by the respondent, was exaggerated, and the CF did not lead any evidence with respect to its funding or budgets during the period when Mr. Buffett was refused coverage for the treatment.

It was therefore impossible to reliably assess the impact, at the time, of any additional costs arising from an expanded range of health coverage. The complaint was substantiated and the respondent was ordered to fund the treatment, subject to the complainant's doctor's recommendations.

| Results for Canadians |

|

Demographic trends in parenting as well as advances in reproductive technology have brought issues surrounding fertility treatment to the fore in Canada. In particular, issues are arising in relation to the ability of a publicly funded health care system to pay for such treatments. The Buffet decision explores the legal relationship between assisted reproduction, and other medical treatments. The decision serves as an important contribution to a legal and policy discourse, which currently engages and affects many Canadians. |

Warman v. Kouba 2006 CHRT 50

This complaint was about whether Mr. Kouba using the pseudonyms "proud18" and "WhiteEuroCanadian" communicated hate messages over the Internet, contrary to s. 13(1) of the CHRA.

The author of the impugned messages used what he called "true stories" and news reports to justify unfounded and racist generalizations. His messages vilified Aboriginal Canadians, Blacks and Jews, characterizing these targeted groups as "sexual predators" and inciting fear that children, women and vulnerable people would fall victim to the criminal and violent sexual impulses of the targeted groups. These messages made it highly likely that members of the targeted groups would be exposed to deep feelings of hatred. The messages also provided readers with scapegoats for the world's problems by offering an outlet for strong negative emotions generated by these problems. Tapping into these emotions and diverting them toward the targeted groups, the messages fostered and legitimized hatred toward members of the targeted groups. All the groups targeted by the material in the present case were characterized as dangerous or violent by nature. All ofthe impugned messages characterized the targeted groups in resoundingly negative terms and did not suggest, in any way, that the members might possess any redeeming qualities. The messages in this case fostered the attitude that members of the targeted groups were so devoid of any redeeming characteristics that extreme hatred or contempt toward them could be entirely justified.

Furthermore, the impugned messages argued that it was hopeless to expect civilized, law-abiding or productive behaviour from the targeted groups and ridiculed any reader who might harbour even a partially open mind toward members of the groups. The messages conveyed the idea that Black and Aboriginal people were so loathsome that white Canadians could not and should not associate with them. Some of the messages associated members of the targeted groups with waste, sub-human life forms and depravity. By denying the humanity of the targeted group members, the messages created the conditions for contempt to flourish.

Moreover, the level of vitriol, vulgarity and incendiary language contributed to the Tribunal's finding that the messages in the case were likely to expose members of the targeted groups to hatred or contempt. The tone created by such language and messages was one of profound disdain and disregard for the worth of the members of the targeted groups. The trivialization and celebration in the postings of past tragedy that afflicted the targeted groups created a climate of derision and contempt that made it likely that members of the targeted groups would be exposed to these emotions. Some of the posted messages invited readers to communicate their negative experiences with Aboriginal people. The goal was to persuade readers to take action. Although the author did not specify what was meant by taking action, the posting suggested that it might not be peaceful. The Tribunal found that the impugned messages regarding Aboriginal Canadians and Jewish people attempted to generate feelings of outrage at the idea of being robbed and duped by a sinister group of people. In this way, the messages created the conditions for hatred of members of these groups to flourish. It was clear that the material presented during the inquiry into this matter from both of the impugned websites was likely to expose members of the targeted groups to hatred or contempt. Undisputed evidence presented by the complainant and the Commission on this issue during the hearing established that the respondent had communicated the hate messages presented in the inquiry. The evidence adduced by the Commission consisted of testimony from a member of the Edmonton Police Force, a Witness Statement Form that was authored and signed by the respondent, and evidence provided by the complainant.

The Tribunal concluded that the Commission had adduced credible evidence that supported its allegation that the respondent had communicated the impugned hate messages over the Internet, and the respondent failed to provide a defence. The Tribunal found the complaint to be substantiated and ordered that the respondent cease the communication of messages like the ones that were the subject of the complaint. The Tribunal also ordered the respondent to pay a penalty of $7,500.00.

| Results for Canadians |

|

Section 13 of the CHRA forms the basis of a significant number of complaints referred to the Tribunal for Inquiry. However, this provision of the CHRA poses unique interpretive challenges for the Tribunal, and Canadians at large. In particular, one must assess the likelihood that a given message will expose persons to hatred or contempt on a prohibited ground of discrimination. In the Kouba decision, this interpretive task has been facilitated through an extensive examination of the Tribunal's s. 13 jurisprudence. The analysis identifies a number of "hallmarks" displayed by communications that have been found to victimize persons within the meaning of the statute. The Tribunal's hallmark analysis unites disparate findings into a more cohesive body of principles. As such, it renders s. 13 more accessible and comprehensible to Canadians. This is particularly important given that s. 13 is the only discriminatory practice set out in the CHRA in relation to which a monetary penalty may be imposed. |

Durrer v. CIBC 2007 CHRT 6

The complainant, Mr. Durrer, had worked for the respondent, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC), for over 28 years when he was told, in 1999, that his position was to be eliminated due to downsizing and restructuring. His termination crystallized in 2002 after three temporary positions. Mr. Durrer filed a complaint with the Canadian Human Rights Commission, alleging discrimination by CIBC on the basis of age. Mr. Durrer complained that, while he did not lose any pension entitlement or benefits, CIBC did not allow him to continue to work to the bridgeable retirement age of 53 years, when he would be entitled to a pension reduction waiver.

The Tribunal considered three questions of discrimination on the basis of age: (1) the elimination of Mr. Durrer's position in 1999, (2) the decision not to transfer Mr. Durrer in 1999; and (3) whether CIBC interfered with Mr. Durrer's attempts to seek redeployment within the company.

In 1999, the new Chief Compliance Officer, Mr. Young, developed criteria to be used for the termination of certain positions within Mr. Durrer's department. The criteria were primarily compliance, experience, understanding and support of a new model for a compliance department. Mr. Young eliminated Mr. Durrer's position for lawful business reasons – the position was redundant, and not needed in CIBC's newly consolidated, single compliance department model. The fact that CIBC saved money by eliminating Mr. Durrer's position does not make the act a discriminatory one under the CHRA. Mr. Young's decision not to offer Mr. Durrer a position in the new compliance department was not made because of the complainant's age, but rather due to Mr. Durrer's admitted status as a "generalist" in a workplace increasingly defined by "specialists". The evidence also indicated that age was not a factor used by Mr. Young to the detriment of Mr. Durrerin relation to the decision to not redeploy him. CIBC provided assistance to Mr. Durrer from the moment he was notified that his position was being eliminated in October 1999. CIBC offered him the maximum 24-month severance package. Mr. Durrer held three temporary positions over a 28-month period. That is probative evidence that CIBC did not frustrate his attempts to find permanent or temporary work on account of his age. The complaint was dismissed.

| Results for Canadians |

|

With the aging of the Canadian workforce, the topic of age discrimination has received new interest from a number of sectors within Canadian society. Further attention was focused on the issue with the Ontario Government's decision to abolish mandatory retirement through amendments that took effect in December of 2006. Given the foregoing, the Tribunal's decision in Durrer constitutes a timely examination of the dynamics present in a workplace when an older employee is laid off. In particular, it addresses the important and related issue of early pension entitlement. Finally, the decision serves as an illustration to Canadian employees and employers that downsizing can occur without targeting older workers. |

Judicial Review of Tribunal Decisions

The majority of the Tribunal's discrimination decisions in fiscal year 2005-2006 were not the subject of judicial review proceedings. As noted in Section 1, we perceive this as an indicator of a greater acceptance of the Tribunal's interpretation of the CHRA by the reviewing courts.

Table 3. Judicial Review of Tribunal Decisions

|

|

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

Total |

|

Cases Referred |

130 |

139 |

99 |

70 |

438 |

|

Decisions Rendered |

12 |

14 |

11 |

13 |

50 |

|

Upheld |

1 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

Overturned |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

J.R. Withdrawn / Struck for Delay |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

|

J.R. Pending |

0 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

6 |

|

TOTAL challenges |

4 |

7 |

2* |

4 |

17 |

*This challenge is really comprised of two separate judicial review applications in respect of one Tribunal decision.

Pay Equity Update

In 1999, the Government of Canada announced its intention to conduct a review of section 11 of the CHRA, "with a view to ensuring clarity in the way pay equity is implemented in the modern workforce." In 2004, the Pay Equity Task Force published its final report, Pay Equity: A New Approach to a Fundamental Right (available at http://www.justice.gc.ca/en/payeqsal/index.html). The Tribunal is awaiting the government's reaction to this report.

Of the four new pay equity cases that were referred to the Tribunal under s.11 of the CHRA, three have settled at mediation and the remaining case is scheduled for hearing in early 2008. All four pay equity cases referred to the Tribunal in 2005 were concluded. Three new pay equity cases were referred to the Tribunal in 2006. Two are scheduled for hearing in late 2007 and the remaining case is still in the case management phase.

Employment Equity Cases

No applications were made in 2006. To date, there are no open cases and no hearings have been held, given that the parties have reached settlements before the commencement of hearings. The EEA was scheduled for parliamentary review in 2005. The Tribunal will await the outcome of the review to assess any impact on its inquiry process.

Section III - Supplementary Information

Organizational Information

Our Organizational Structure

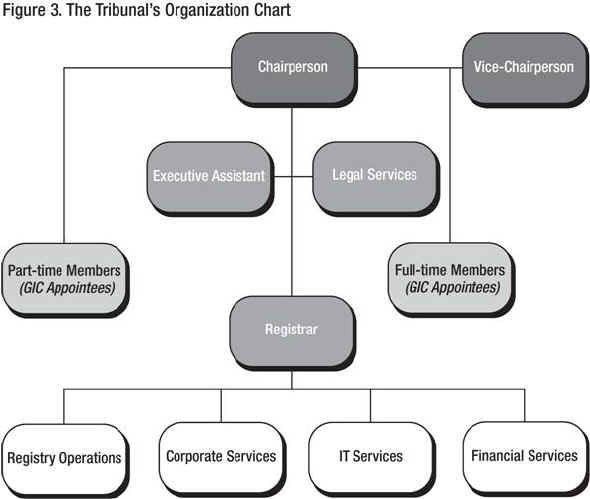

Members

The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal is a small, permanent organization, comprising a full-time Chairperson and Vice-Chairperson and up to 13 full- or part-time members (see Figure 3). Under the statute, both the Chairperson and the Vice-Chairperson must have been members of the bar for more than 10 years.

To be eligible for appointment by the Governor-in-Council, all members of the Tribunal are required to have expertise in, and sensitivity to, human rights issues. In addition, members attend regular meetings for training and briefing sessions on such topics as decision-writing techniques, evidence and procedure, and in-depth analysis of human rights issues. Throughout their three- or five-year terms, all tribunal members are given opportunities for professional development. The level of expertise and skill of members is undoubtedly at the highest level it has been since the creation of the Tribunal in 1978.

Registry Operations

Administrative responsibility for the Tribunal rests with the Registry. It plans and arranges hearings, acts as liaison between the parties and tribunal members, and provides administrative support. The Registry is also accountable for the operating resources allocated to the Tribunal by Parliament.

Corporate, Financial, Legal and Information Technology Services

Tribunal and Registry operations are supported by Corporate Services, Financial Services, Legal Services and Information Technology (IT) Services.

Corporate Services provides support to the Tribunal in facilities management, communications, material management, procurement of goods and services, information management, security, reception and courier services. It also assists the Registrar's Office in the development, implementation and monitoring of government-wide initiatives.

Financial Services provides the Tribunal with accounting services, financial information and advice.

Legal Services provides the Tribunal with legal information, advice and representation.

The main priority of IT Services is to ensure that the Tribunal has the technology required to perform efficiently and effectively. The section advises Registry staff and members on the use of corporate systems and technology available internally and externally, and offers training. It also provides procurement and support services for all computer hardware, software and information technology services. IT Services is involved in implementing government initiatives, such as Government On-Line, and represents the Tribunal on the Electronic Filing Project Advisory Committee, a committee that includes government agencies involved in either court or administrative legal activities.

Human resources services are contracted out to the Department of Public Works and Government Services Canada.

Table 4. Comparison of Planned to Actual Spending (including Full-Time Equivalents)

|

|

2006-2007 |

|||||

|

($ millions) |

2004-2005 Actual |

2005-2006 Actual |

Main Estimates |

Planned Spending |

Total Authorities |

Total Actuals |

|

Public hearings under Canadian Human Rights Act |

4.2 |

3.8 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.6 |

4.6 |

|

Total |

4.2 |

3.8 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.6 |

4.6 |

|

Less: Non-Respendable revenue |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Plus: Cost of services received without charge |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

|

Total Departmental Spending |

5.3 |

5.0 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.8 |

5.8 |

|

Full Time Equivalents |

26 |

26 |

|

|

|

26 |

Table 5. Resources by Program Activity (Millions of Dollars)

|

2006–2007 |

||||||||

|

|

Budgetary |

Plus: Non- |

Total |

|||||

|

Program Activity |

Operating |

Capital |

Grants and Contrib- |

Total: Gross Budgetary Expend- |

Less: Respendable Revenue |

Total: Net Budgetary Expend- |

Loans, Investments and Advances |

|

|

Public hearings under Canadian Human Rights Act |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Main Estimates |

4.3 |

|

|

4.3 |

|

4.3 |

|

4.3 |

|

Planned Spending |

4.3 |

|

|

4.3 |

|

4.3 |

|

4.3 |

|

Total Authorities |

4.6 |

|

|

4.6 |

|

4.6 |

|

4.6 |

|

Actual Spending |

4.6 |

|

|

4.6 |

|

4.6 |

|

4.6 |

Table 6. Voted and Statutory Items (Millions of Dollars)

|

|

2006-2007 |

||||

|

Vote or Statutory Item |

Truncated Vote or Statutory Wording |

Main Estimates |

Planned Spending |

Total Authorities |

Total Actuals |

|

15 |

Program expenditures |

3.9 |

3.9 |

4.2

|

4.2 |

|

(S) |

Contributions to employee benefit plans |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

|

|

Total |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.6 |

4.6 |

Table 7. Services Received Without Charge

|

($ millions) |

2006–07 Actual Spending |

|

Accommodation provided by Public Works and Government Services Canada |

1.0 |

|

Contributions covering employers' share of employees' insurance premiums and expenditures paid by Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (excluding revolving funds). Employer's contribution to employees' insured benefits plans and associated expenditures paid by the Treasury Board Secretariat |

0.2 |

|

Salary and associated expenditures of legal services provided by the Department of Justice Canada |

0 |

|

Total 2006–2007 services received without charge |

1.2 |

Financial Statements

Financial Statements are prepared in accordance with accrual accounting principles. The supplementary information presented in the financial tables in the Departmental Performance Report is not audited, rather prepared on a modified cash basis of accounting in order to be consistent with appropriations-based reporting. Note 3 of the financial statements reconciles these two accounting methods.

Canadian Human Rights Tribunal Statement of Management Responsibility

Responsibility for the integrity and objectivity of the accompanying financial statements for the year ended March 31, 2007 and all information contained in these statements rests with departmental management. These financial statements have been prepared by management in accordance with Treasury Board of Canada accounting policies, which are consistent with generally accepted Canadian accounting principles for the public sector.

Management is responsible for the integrity and objectivity of the information in these financial statements. Some of the information in the financial statements is based on management's best estimates and judgment, and gives due consideration to materiality. To fulfill its accounting and reporting responsibilities, management maintains a set of accounts that provides a centralized record of the department's financial transactions. Financial information submitted to the Public Accounts of Canada and included in the department's DPR is consistent with these financial statements.

Management maintains a system of financial management and internal control designed to provide reasonable assurance that: financial information is reliable; assets are safeguarded; and transactions, in accordance with the Financial Administration Act, are executed in accordance with prescribed regulations, within parliamentary authorities, and are properly recorded to maintain accountability of Government funds.

Management also seeks to ensure the objectivity and integrity of data in its financial statements by careful selection, training and development of qualified staff, by organizational arrangements that provide appropriate divisions of responsibility, and by communication programs aimed at ensuring that regulations, policies, standards and managerial authorities are understood throughout the department.

The financial statements of the department have not been audited.

|

J. Grant Sinclair |

Gregory M. Smith |

Canadian Human Rights Tribunal

Statement of Operations (unaudited) for the year ended March 31

(in dollars)

|

|

2007 |

2006 |

|

|

Expenses |

|

|

|

|

Operating Expenses: |

|

|

|

|

|

Salaries and employee benefits |

2,564,490 |

2,616,790 |

|

|

Rentals |

1,320,641 |

1,120,483 |

|

|

Professional Services |

1,223,070 |

829,918 |

|

|

Transportation and Telecommunications |

452,578 |

268,546 |

|

|

Materials and Supplies |

68,982 |

85,731 |

|

|

Amortization |

51,545 |

38,413 |

|

|

Communications |

39,892 |

36,576 |

|

|

Repair and Maintenance |

25,469 |

15,250 |

|

|

Miscellaneous |

9,700 |

7,701 |

|

Total Expenses |

5,756,367 |

5,019,408 |

|

|

Revenues |

|

|

|

|

Other revenue |

25 |

230 |

|

|

Total Revenues |

25 |

230 |

|

|

Net Cost of Operations |

5,756,342 |

5,019,178 |

|

|

The accompanying notes form an integral part of these financial statements. |

|||

Canadian Human Rights Tribunal

Statement of Financial Position (unaudited) at March 31

(in dollars)

|

|

2007 |

2006 |

|

|

Assets |

|

|

|

|

Financial assets |

|

|

|

|

|

Receivables from other Federal Government departments and agencies |

48,279 |

19,342 |

|

|

Receivables from external parties |

4,692 |

964 |

|

|

Employee Advances |

500 |

500 |

|

|

Total des actifs financiers |

53,471 |

20,806 |

|

Non-financial assets |

|

|

|

|

|

Prepaid expenses |

14,000 |

14,000 |

|

|

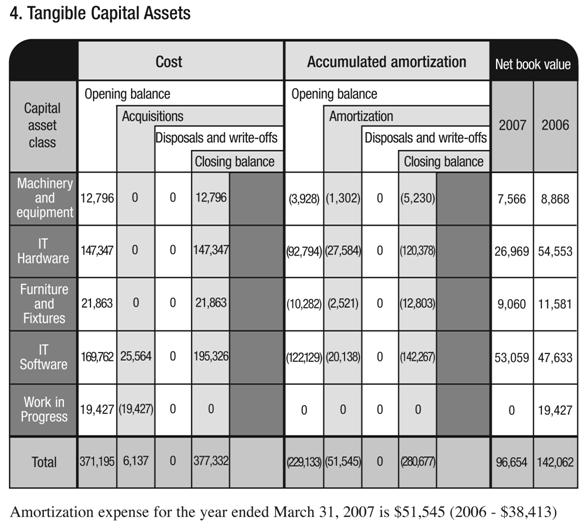

Tangible capital assets (Note 4) |

96,654 |

142,062 |

|

|

Total des actifs non financiers |

110,654 |

156,062 |

|

Total |

164,125 |

176,868 |

|

|

Liabilities |

|

|

|

|

|

Accounts payable to other Federal Government departments and agencies |

31,916 |

61,725 |

|

|

Other accounts payable and accrued liabilities |

351,087 |

210,722 |

|

|

Vacation pay and compensatory leave |

83,511 |

95,633 |

|

|

Employee severance benefits (Note 5b) |

431,825 |

431,825 |

|

|

Total |

898,339 |

799,905 |

|

Equity of Canada |

(734,214) |

(623,037) |

|

|

Total |

164 ,125 |

176,868 |

|

|

Contractual Obligations (Note 6) |

|||

Canadian Human Rights Tribunal

Statement of Equity of Canada (unaudited) for the year ended March 31

(in dollars)

|

|

2007 |

2006 |

|

Equity of Canada, beginning of year |

(623,037) |

(656,263) |

|

Net cost of operations |

(5,756,342) |

(5,019,178) |

|

Current year appropriations used (Note 3) |

4,561,439 |

3,804,022 |

|

Revenue not available for spending |

(25) |

(125) |

|

Refund of previous year expenses |

(4,300) |

(6,305) |

|

Change in net position in the Consolidated Revenue Fund (Note 3) |

(77,891) |

89,466 |

|

Services received without charge from other government departments and agencies (Note 7) |

1,165,942 |

1,165,346 |

|

Equity of Canada, end of year |

(734,214) |

(623,037) |

| The accompanying notes form an integral part of these financial statements. | ||

Canadian Human Rights Tribunal

Statement of Cash flow (unaudited) for the year ended March 31

(in dollars)

|

|

2007 |

2006 |

|

|

Operating activities |

|

||

|

|

Net cost of operations |

5,756,342 |

5 019,178 |

|

Non-cash items: |

|

|

|

|

|

Amortization of capital assets |

(51,545) |

(38,413) |

|

|

Services provided without charge by other government departments |

(1,165,942) |

(1,165,346) |

|

Variations in Statement of Financial Position: |

|

|

|

|

|

Increase (decrease) in accounts receivables and advances |

32,665 |

(114,346) |

|

|

Increase (decrease) in liabilities |

(98,434) |

109,453 |

|

Cash used by operating activities |

4,473,086 |

3,810,526 |

|

|

Capital investment activities |

|

|

|

|

Acquisitions of tangible capital assets |

6,137 |

76,532 |

|

|

Financing Activities |

|

|

|

|

Net cash provided by Government of Canada |

4,479,223 |

3,887,058 |

|

| The accompanying notes and schedules form an integral part of these Statements | |||

Canadian Human Rights Tribunal

Notes to the Financial Statements (unaudited)

1. Authority and Objectives

The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (the Tribunal) is a quasi-judicial body created by Parliament to inquire into complaints of discrimination and to decide if particular practices have contravened the Canadian Human Rights Act. The Tribunal may only inquire into complaints referred to it by the Canadian Human Rights Commission, usually after a full investigation by the Commission. The Commission resolves most cases without the Tribunal's intervention. Cases referred to the Tribunal generally involve complicated legal issues, new human rights issues, unexplored areas of discrimination, or multifaceted evidentiary complaints that must be heard under oath.

The Tribunal's mandate also includes hearing matters under the Employment Equity Act.

2. Summary of Significant Accounting Policies

These financial statements have been prepared in accordance with Treasury Board of Canada accounting policies which are consistent with generally accepted Canadian accounting principles for the public sector.

Significant accounting policies are as follows:

a) Parliamentary Appropriations – The Tribunal is primarily financed by the Government of Canada through parliamentary appropriations. Appropriations provided to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal do not parallel financial reporting according to generally accepted accounting principles since they are primarily based on cash flow requirements. Consequently, items recognized in the statement of operations and the statement of financial position are not necessarily the same as those provided through appropriations from Parliament. Note 3 provides a high level reconciliation between the bases of reporting.

b) Net Cash Provided by Government – The Tribunal operates within the Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF), which is administered by the Receiver General for Canada. All cash received by the Tribunal is deposited to the CRF and all cash disbursements made by the Tribunal are paid from the CRF. The net cash provided by Government is the difference between all cash receipts and all cash disbursements including transactions between departments of the federal government.

c) Change in Net Position in the Consolidated Revenue Fund is the difference between the net cash provided by Government and appropriations used in a year, excluding the amount of non-respendable revenue recorded by the department. It results from timing differences between when a transaction affects appropriations and when it is processed through the CRF.

d) Revenues – These are accounted for in the period in which the underlying transaction or event occurred that gave rise to the revenues.

e) Expenses – Expenses are recorded on the accrual basis:

- Vacation pay and compensatory leave are expensed as the benefits accrue to employees under their respective terms of employment.

- Services provided without charge by other government departments for accommodation, the employer's contribution to the health and dental insurance plans and legal services are recorded as operating expenses at their estimated cost.

f) Employee Future Benefits

- Pension Benefits: Eligible employees participate in the Public Service Pension Plan, a multiemployer plan administered by the Government of Canada. The Tribunal's contributions to the Plan are charged to expenses in the year incurred and represent the total departmental obligation to the Plan. Current legislation does not require the department to make contributions for any actuarial deficiencies of the Plan.

- Severance Benefits: Employees are entitled to severance benefits under labour contracts or conditions of employment. These benefits are accrued as employees render the services necessary to earn them. The obligation relating to the benefits earned by employees is calculated using information derived from the results of the actuarially determined liability for employee severance benefits for the Government as a whole.

g) Accounts Receivable and Advances are stated at amounts expected to be ultimately realized; a provision is made for receivables where recovery is considered uncertain.

h) Tangible Capital Assets – All tangible capital assets and leasehold improvements having an initial cost of $5,000 or more are recorded at their acquisition cost. Amortization of tangible capital assets is done on a straight-line basis over the estimated useful life of the asset as follows:

|

Asset Class |

Amortization Period |

|

Machinery and equipment |

5 to 10 years |

|

Furniture and fixtures |

10 years |

|

Informatics Hardware & Software |

3 years |