Common menu bar links

Breadcrumb Trail

ARCHIVED - Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada - Report

This page has been archived.

This page has been archived.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Message from the Information Commissioner of Canada

I am pleased to present the Office of the Information Commissioner’s Report on Plans and Priorities for 2012–2013. This report sets out our continuous efforts and initiatives to effectively defend Canadians’ right of access to public sector information and to facilitate greater government transparency and accountability.

Three years ago, strategically and aggressively, my Office introduced a new way of doing business. We undertook to eliminate the historical backlog of complaints that was preventing us to deliver timely service to Canadians. Processes were streamlined to quickly resolve straightforward administrative complaints so that investigators could focus on the more challenging cases about access refusal. This led to a substantial dent in our inventory.

We have now intensified our efforts to address the complex and often voluminous nature of refusal cases. Our portfolio approach to investigations and our process for complaints involving sensitive national security issues have proven their worth. We will hone on these strategies to become more efficient in resolving complex and priority cases. To sustain these efforts, we must also ensure a sound work environment with the proper tools, training, service standards and controls.

However, the path forward is ripe with challenges. Among those are the increased financial pressures stemming from the reductions to our appropriations announced in Budget 2012. Just as important is the systemic impact that government-wide budget cuts and downsizing could have on the access regime as a whole.

In my view, our overarching priority to increase efficiencies in investigating and resolving complaints while maintaining high quality standards is now seriously at risk. This in turn will have a negative impact on Canadians’ right of access. We will need to closely review our plans and activities accordingly.

This year, as institutions strive to increase efficiencies, the thirtieth anniversary of the Access to Information Act provides a timely opportunity to explore collectively how reform initiatives would bring about a more efficient access regime. The long-overdue modernization of the legislation could help bring the regime into the digital age and up to par with the most progressive models of transparency.

Today, nations around the world develop or refine open government initiatives. Openness is more than just open data. Without access to information, open government is just about the information that institutions volunteer to release. A modern, effective access to information regime would provide Canadians with the means to access the information that they request as well as the proper check and balance that our democracy deserves.

Suzanne Legault

Information Commissioner of Canada

Section I: Organizational Overview

Raison d’être

The Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada (OIC) ensures that federal institutions respect the rights that the Access to Information ActEndnote 1 confers to information requesters. Protecting and advancing the right of access to public sector information ultimately enhances the transparency and accountability of the federal government.

Responsibilities

The OIC is an independent public body set up in 1983 under the Access to Information Act. Our mission is to conduct efficient, fair and confidential investigations into complaints about federal institutions’ handling of access to information requests. The goal is to maximize compliance with the Act while fostering disclosure of public sector information using the full range of tools, activities and powers at the Commissioner’s disposal, from information and mediation to persuasion and litigation, where required. Endnote 2

We use mediation and persuasion to resolve complaints. In doing so, we give complainants, heads of federal institutions and all third parties affected by complaints a reasonable opportunity to make representations. We encourage institutions to disclose information as a matter of course and to respect Canadians’ rights to request and receive information, in the name of transparency and accountability. We bring cases to the Federal Court to ensure that the Act is properly applied and interpreted with a view to maximizing disclosure of information.

We also support the Information Commissioner in her advisory role to Parliament and parliamentary committees on all matters pertaining to access to information. We actively make the case for greater freedom of information in Canada through targeted initiatives such as Right to Know Week,Endnote 3 and ongoing dialogue with Canadians, Parliament and federal institutions.

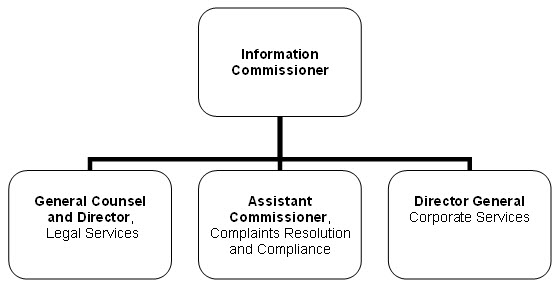

The following diagram shows the OIC’s organizational structure.

Legal Services represents the Commissioner in court and provides legal advice on investigations, legislative issues and administrative matters. It closely monitors the range of cases having a potential impact on our mandate and on access to information in general. Legal Services also assists investigators by providing them with up-to-date and customized reference tools on the evolving technicalities of the case law.

The Complaints Resolution and Compliance Branch investigates individual complaints about the processing of access requests, conducts dispute resolution activities and makes formal recommendations to institutions, as required. It also assesses federal institutions’ compliance with their obligations, and carries out systemic investigations and analysis.

Corporate Services provides strategic and corporate leadership in planning and reporting, communications, human resources and financial management, security and administrative services, internal audit as well as information management and technology. It conducts external relations with a wide range of stakeholders, notably Parliament, government and representatives of the media. It is also responsible for managing our access to information and privacy function.

Strategic Outcome and Program Activities

Strategic Outcome

Individuals’ rights under the Access to Information Act are safeguarded.

Program Activities

- Compliance with access to information obligations

- Internal services

Organizational Priorities

| Priority | Type | Program Activity |

|---|---|---|

|

Exemplary service delivery to Canadians: Increase efficiencies in investigating and resolving all types of complaints while maintaining high quality standards. |

Previously committed to |

Compliance |

| Description | ||

|

Why is this a priority? Just as Canadians have the right to obtain timely access to government information, complainants have the right to obtain a timely resolution of complaints they have filed with the Information Commissioner. Effective and timely investigative performance is the overarching goal behind the business model the OIC started implementing in 2008. Since then, the streamlining of our business processes, a new case management system, the close monitoring of inventory and performance metrics, two internal audits as well as refined strategies to manage our caseload have significantly improved our operations. We have reduced our inventory of complaints by 27 percent since the end of 2008–2009. We are now intensifying our efforts to achieve a manageable carry-over of 500 cases at year end by 2015–2016. Plans for meeting the priority Case management strategies

Tools, systems, processes and standards

|

||

Type is defined as follows: previously committed to—committed to in the first or second fiscal year prior to the subject year of the report; ongoing—committed to at least three fiscal years prior to the subject year of the report; and new—newly committed to in the reporting year of the Report on Plans and Priorities or Departmental Performance Report.

| Priority | Type | Program Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Timeliness of responses to access requests: Complete our diagnostic of delay-related issues and follow up on the progress achieved by institutions | Previously committed to | Compliance |

| Description | ||

|

Why is this a priority? Responding to access requests in a timely fashion is one of the cornerstones of the Access to Information Act. In 2009, we undertook a three-year exercise to assess and document the root causes of delay-related issues.Endnote 4 The methodology combined findings from investigations of complaints, performance assessments of select groups of institutions and in-depth analysis of systemic or recurrent issues. Our objective was to provide evidence-based advice to Parliament and assist central agencies and individual institutions in implementing effective remedies. The exercise was also intended to encourage institutions to proactively seek greater compliance with access to information obligations. In 2012–2013, we will complete our diagnostic and examine the extent to which recommendations for improvement have been implemented. Plans for meeting the priority

|

||

| Priority | Type | Program Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Expertise for a modern access to information regime: Continue to promote the modernization of access to information as a key component of the broader concept of open government. | Previously committed to | Legal and Internal ServicesEndnote 5 |

| Description | ||

|

Why is this a priority? Open government initiatives and an obsolete access regime tend to obfuscate the fact that access to information remains the primary bulwark and key measure of government openness and transparency. Over time, numerous stakeholders have developed agendas for reform, but the legislation has remained essentially intact. In 2011, the Speech from the Throne and several other developments gave impetus to open government at the federal level. In his letter to U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on September 19, 2011, Minister Baird conveyed Canada’s intent to join the international Open Government Partnership. A common expectation among stakeholders is that legislative reform and improved compliance with access to information obligations must be part of Canada’s Open Government action plan. In 2012–2013, we will provide informed input on the necessary amendments to the Access to Information Act in light of its thirtieth anniversary. Plans for meeting the priority

|

||

| Priority | Type | Strategic Outcome(s) and/or Program Activity(ies) |

|---|---|---|

| An exceptional workplace: Implement our Integrated HR-Business Plan with a focus on developing, recruiting and retaining talent. | Previously committed to | Internal Services |

| Description | ||

|

Why is this a priority? Creating and maintaining an exceptional workplace is a key objective of our 2011–2014 Strategic Plan.Endnote 6 Talent management will enable us to develop, attract and retain individuals with the right skills for the job. We are also strengthening our enabling infrastructure as we improve how we work, where we work and the tools with which we work. In doing so, we will embrace new technologies, foster collaboration and innovation, and facilitate information and knowledge management. To the extent that our workplace builds upon and reflects the common values that we share as individuals and public servants, our service delivery and interactions with our various constituencies will also benefit. Plans for meeting the priority Talent management

Enabling infrastructure

Values and ethics

Public Service Employee Survey

|

||

| Priority | Type | Strategic Outcome(s) and/or Program Activity(ies) |

|---|---|---|

| Governance: Ensure and demonstrate both fiscal responsibility and responsible stewardship. | Previously committed to | Compliance and Internal Services |

| Description | ||

|

Why is this a priority? In periods of fiscal restraint, public sector institutions must rethink their program activities and service delivery in terms of results, efficiency, effectiveness and cost savings opportunities. As “back-office functions,” internal services are often the most vulnerable to budget restrictions. Yet, it is in these very moments that their contributions are the most valuable - to inform and engage, to measure and assess performance, to lead in the quest for greater efficiencies, to mitigate risks, and to ensure continued compliance with all applicable laws and policies. Parliament and Canadians seek greater reassurance of the prudent stewardship of public funds, the safeguarding of public assets, and the efficient use of public resources. To this end, they expect reliable reporting of how public funds achieve results for Canada and Canadians. To meet these expectations, we will further strengthen and document our corporate system of internal control in 2012–2013. We will fine-tune and expand our performance measurement framework across the organization. We will also take part in shared services that enable us to reduce risks and costs while improving service delivery. Plans for meeting the priority Policy compliance

Performance measurement and evaluation

Shared services

|

||

Risk Analysis

The strategic planning exerciseEndnote 7 conducted in 2010 and the subsequent update of our risk-based audit planEndnote 8 provided opportunities to review our business risks and devise appropriate responses or mitigation strategies. These strategies as well as ongoing developments have since substantially modified our risk profile. The following section summarizes our most important risks, their causes, potential impact or outcomes, as well as mitigation strategies that are already in place or require implementation.

Financial Resources

The operating budget freeze introduced with Budget 2010 has removed the limited financial flexibility the Office previously had. Our year-end lapse of funds was 1.7 percent and 1.2 percent of authorities in the last two years. In 2010–2011, we had to request authority to access $400K in additional funding to accommodate the increase in workload due to litigation and complex cases.

Our program and expenditure review conducted in the context of the government’s Deficit Reduction Action Plan indicates that any reductions to our existing appropriations would significantly impact program results.Endnote 9 Such reductions would compromise our ability to deal with the demands of our current inventory and to meet other corporate obligations, such as policy compliance. Any unexpected event that would impact our workload would create significant financial pressures on the organization.

We also face uncertainty due to the fact that we have to relocate our offices in 2013. Preliminary estimates from Public Works and Government Services Canada indicate that the cost could be as high as $3M. We have yet to secure a source of funding.

Workload and Project Management

Our workload is considerably influenced by the way in which federal institutions handle information requests and by the number, complexity and priority of complaints subsequently made to the Commissioner. The pace and outcome of complex or systemic investigations depend on various factors, not the least of which is cooperation from institutions, complainants and witnesses. Court decisions on access-related cases can also impact our workload. There is a risk that significant and unexpected fluctuations in workload may prevent us from meeting our targets and other obligations in a timely fashion.

Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) statistics for 2010–2011 indicate an increase of 18 percent in the number of access requests received by institutions.Endnote 10 Historically, 5-6 percent of requests generate complaints to our Office. If this trend materializes, we could be faced with an influx of 2,000 to 2,500 new complaints in 2012–2013. Worth noting, several of the top 10 institutions to receive access requests are also among the top 10 institutions generating complaints. Hence, a potential risk in terms of increased workload.

This risk is now compounded by the fact that institutions, in times of restraint, tend to cut in their internal services, which include Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) programs. The consequences of such cuts could include failure to meet legal requirements, declining performance and an increase in complaints.

Moreover, our inventory of complaints has changed substantially in recent years. In 2007–2008, it included a near equal share of administrative and refusal complaints. The former pertain to delays, extensions, fees or similar issues. Refusal complaints, on the other hand, involve the application or interpretation of exemptions to the right of access, including exemptions for information dealing with national security and other sensitive matters.

Currently, 88 percent of our workload consists of refusal complaints. This results from increased efficiencies in resolving administrative complaints as well as a higher proportion of new refusal complaints. We also note a measurable increase in complexity among the most recent cases investigated.

By nature, investigations of refusal complaints tend to be more complex or contentious and therefore may take longer to complete. In some instances, they may require the recourse to the Commissioner’s formal investigative powers (e.g. issuing subpoenas and conducting examinations under oath). Refusal complaints may also give rise to proceedings before the Federal Court to clarify the interpretation and application of the Act or ensure compliance with the legislation.

Litigation can affect our workload by putting some investigations on hold for an extended period of time. For example, the Federal Court of Appeal rendered a decision last year regarding the application of a provision introduced with the Federal Accountability Act. This decision had the effect of reactivating 174 files that had been on hold for approximately two years.

To address our workload risks and operational requirements, we introduced strategies to deal specifically with complex and priority cases. An internal audit conducted in the spring of 2011 led to improvements in file documentation and environmental scanning to support efficient and timely case management.Endnote 11 In 2012–2013, the introduction of an evaluation function will help mitigate risks of not achieving established objectives by providing additional performance feedback. We will also closely monitor the impact of deficit reduction plans on ATIP operations across the system.

Litigation

The OIC must deal on an ongoing basis with the likelihood of litigation relating to institutions’ non-compliance with the Act and court decisions. The higher percentage of refusal cases in our inventory has increased the risks of litigation. To mitigate those risks, we resort to various means under our “compliance continuum,” including using investigative tools that reduce the demand on institutions, early involvement of Legal Services, as well as senior management’s intervention to communicate expectations and maintain a climate of cooperation.Endnote 12

In May 2011, the Supreme Court of Canada issued its decision regarding access to records located in the Prime Minister’s and Ministers’ offices. The Court set out a two-step test to determine if such records are under the control of the government institution. However, the absence of a clear-cut distinction between ministerial and departmental records could lead to challenging and time-consuming investigations, possibly requiring the use of the Commissioner’s formal powers. It could also lead to increased court activity, with a concomitant increase in the time and resources needed to effectively prepare and present the Commissioner’s arguments.

The same can be said about some of the new exclusions and exemptions brought in under the Federal Accountability Act. These could lead more institutions and requesters to test the limits of these provisions before the courts. In 2011–2012, we augmented internal legal capacity to assist with formal investigations and litigation at all court levels. This will contribute to reducing our reliance on costly external professional services. We have also undertaken a review of the access to information legislation to identify and document shortcomings, including issues that increase the risk of litigation.

Human Resources and Knowledge Management

There are two main types of risks associated with human resources (HR). There is the risk that the number of resources, or capacity, may not be sufficient to meet business requirements. There is also the risk that the level of skills and experience, or capability, may not be adequate, given the nature or evolution of those requirements.

In 2009 and 2010, the OIC engaged in a number of staffing actions to fill all required investigative positions. Since then, recruitment strategies under the 2009–2014 Integrated HR Plan have proven effective in minimizing the impact of ongoing staff turnover, due notably to retirement and the high demand for access professionals. However, given the small size of the organization, there is a risk that productivity may be substantially hampered by temporary leaves due to illness or family obligations, for example. The relocation of our offices in 2013 also presents risks for productivity and human resources retention.

With respect to HR capability, the specificity of our core program and the high percentage of new recruits present a significant challenge. OIC demographics show that in January 2011, 57 percent of investigators had fewer than three years of experience among us. Moreover, nearly one third of investigators and several directors will soon be eligible to retire.

Compounding these risks is the fact that corporate memory and integrated skills rest with a small number of individuals who often occupy unique, managerial or multifunctional positions.

As a critical mitigation strategy, talent management enables us to develop and maintain expertise in the particulars of our investigative function. We must also develop succession plans and adequate processes across the organization to ensure smooth transition and transfer knowledge in the event of turnover.

Information Management and Technology

As we start year 4 of our five-year renewal strategy for information management and information technology (IM/IT), the focus is on infrastructure consolidation and network hardening. Consolidation offers a means to achieve significant cost savings while improving performance and supporting future increases in capacity.

In light of a risk assessment conducted in 2010, network hardening will address security vulnerabilities through the implementation of software updates, new security systems, and better configurations and operation policies. These measures will help ensure that our technology complies with the Policy on Government Security and is consistent with government-wide direction and guidance regarding communication and information management.

As we prepare to relocate in a Workplace 2.0 environment, we also need to complete the development and implementation of our information management framework. This framework must allow us, in particular, to fully meet the objective of the government’s Directive on Recordkeeping.

Despite many potential benefits, the use of Web 2.0 presents a number of risks and challenges. For example, it may be difficult to reconcile certain policy obligations (e.g. equal use of official languages) with technological constraints (e.g. per-message characters). Official information might be misused or shared without the proper context, possibly leading to misinterpretation or negative perceptions. There are also challenges in protecting the privacy of personnel and citizens who are interacting online. In addition to mitigating these risks, we need to comply with new standards designed to ensure the accessibility of websites and the usability of Web information, tools and services.

Given the number and complexity of projects involved, there is a risk of not being fully compliant with all IM/IT-related policy instruments by the set timelines. As the Office is expected to demonstrate exemplary practices, such outcomes could also substantially compromise our reputation.

Accountability and Policy Compliance

Similar to other federal institutions, the OIC is subject to a number of government policies and regulations. Due to ongoing changes, these instruments need to be constantly monitored, and the adequacy of internal controls must be re-assessed accordingly. This creates a challenge for a small organization like the OIC.

An additional challenge stems from the fact that the Commissioner, as an independent Agent of Parliament, is solely responsible for monitoring and ensuring compliance with certain policy provisions, as appropriate. In some areas, the Commissioner’s accountability for compliance has been heightened with the Accounting Officer role and the obligation to appear before parliamentary committees, when requested.

In 2012–2013, we will concentrate on operationalizing key controls pertaining to human resources management. We have undertaken discussions to procure human resources services from the Shared Services Unit of Public Works and Government Services Canada. We will also work with the Public Service Commission to implement, as appropriate, any recommendations stemming from a staffing audit initiated at the end of 2011–2012.

Planning Summary

Since 2008, we have addressed resource shortfalls, whenever possible, through internal reallocations and reorganizations. We have continuously improved business processes, which have led to significant operational efficiencies. The benefits have been reinvested to strengthen our program delivery, to respond to unexpected changes in workload, and to manage within our funding envelope.

Following the operating budget freeze introduced in 2010, we developed a strategy to minimize our reliance on our Operating and Maintenance (O&M) budget to cover salary increases from signed collective agreements. The strategy ensured us sufficient O&M funds to cover both fixed operating costs and program-related costs.

In the context of the government’s Deficit Reduction Action Plan, we reviewed our program, operations and internal services to assess results, opportunities for greater efficiency and effectiveness, and potential cost savings.Endnote 13 The review indicated that any reductions to our appropriations would have significant adverse impact on program results. Reductions would erode the benefits and efficiency gains from previous investments in our program and compromise its future sustainability.

We also conducted a four-year comparative analysis of operating expenditures with other departments of similar size. Results showed that the average O&M cost per OIC FTE is at the lower end of the range and will be further reduced by 2014–2015. We anticipate that our O&M expenditures will decrease by 50 percent compared to 2010–2011.

The Financial Resources table below provides the total planned spending (including employee benefit plans) for the Office of the Information Commissioner for the next three fiscal years. Variations in year-over-year are mainly attributable to information management and information technology (IM/IT) initiatives. These figures do not reflect reductions to our funding envelope introduced with Budget 2012.

Financial Resources ($ thousands)

| 2012–13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 |

|---|---|---|

| 11,708 | 11,760 | 11,493 |

The next table provides a summary of the total planned human resources for the Office of the Information Commissioner for the next three fiscal years. The numbers do not reflect the potential impact of announced budget cuts.

Human Resources (FTEs)

| 2012–13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 |

|---|---|---|

| 106 | 106 | 106 |

Planning Summary Table

The following table displays the distribution of financial resources between the OIC’s core program activity and internal services. In 2011–2012, the $1,836K difference in forecast spending as compared to 2012–2013 is primarily due to funding received for paylist requirements of $1,300K. Paylist requirements relate to the government’s legal requirements as employer for items such as parental benefits and severance payments. In 2011–2012, following changes to collective agreements, members of some bargaining units could opt for immediate payout of their accumulated severance pay. The difference in forecast planning also results from a carry forward of $235K, a collective agreement adjustment of $2K, as well as 2012–2013 budget adjustments of $31K to Employee Benefit Plans and $268K for IM/IT renewal initiatives.

| Program Activity |

Forecast

Spending 2011–12 |

Planned Spending | Alignment to Government of Canada Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012–13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | |||

| Compliance with Access to Information Obligations | 8,701 | 8,174 | 8,174 | 8,174 | Government Affairs: A transparent, accountable and responsive federal government |

| Internal Services | 4,821 | 3,534 | 3,586 | 3,319 | |

| Total Forecast | 13,522 | ||||

| Total Planned Spending | 11,708 | 11,760 | 11,493 | ||

Note: Planned spending is composed of approved reference levels from the previous year’s closed Annual Reference Level Update and adjustments to those reference levels, such as amounts received through Supplementary Estimates.

Expenditure Profile

For the 2012–2013 fiscal year, the OIC plans to spend a total of $11,708K to meet the expected results of its program activities and contribute to its long-term strategic outcome. The OIC is committed to ensuring that the financial resources will be used in the most strategic and responsible manner to continue to improve the efficiency of service delivery to Canadians as well as the impact of activities aimed at fostering a leading access to information regime.

Approximately 75 percent of the OIC’s budget will be allocated to salaries and 25 percent for Operating and Maintenance (O&M) costs. Of the O&M budget, a third relates to fixed costs.

The following figure illustrates the Office’s spending trend from 2009–2010 to 2014-2015. The trend shows that actual spending increased, due to staffing and to funding for IM/IT renewal initiatives. The increase in forecast spending reflects primarily paylist requirements associated with payouts of accumulated severance pay. We will need to review our planned expenditures in light of Budget 2012.

Estimates by Vote

For information on organizational appropriations and/or statutory expenditures, please see the 2012–2013 Main Estimates publication.