ARCHIVED - MILESTONES TO THE MILLENNIUM: Serving the Public Good

This page has been archived.

This page has been archived.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

MILESTONES TO THE MILLENNIUM:

Serving the Public Good

August 2000

Table of Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- 1. 1867: LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS

- 2. 1918: MOVING TO MERIT

- 3. 1921: MERIT AND MARRIAGE

- 4. 1924: JOBS FOR LIFE?

- 5. 1931: TREASURY TRIUMPHS

- 6. 1940: LEADING THE PUBLIC SERVICE

- 7. 1951: CONTROLLING EXPENDITURES

- 8. 1961: PROTECTING MERIT AND MANAGING PEOPLE

- 9. 1962: LETTING MANAGERS MANAGE

- 10. 1967: STRIKING DEVELOPMENTS

- 11. 1968: DECISIONS, DECISIONS

- 12. 1969: LINKING PROGRAMS AND BUDGETS

- 13. 1969: HELLO/BONJOUR

- 14. 1970: WOMEN AND THE PUBLIC SERVICE

- 15. 1977: SHRINKING THE PUBLIC SERVICE

- 16. 1977: HARDENING OF THE AUDITORS

- 17. 1979: MAKING MANAGERS MANAGE

- 18. 1979: WHAT ABOUT THE PEOPLE?

- 19. 1982: "CHARTERING" THE PUBLIC SERVICE

- 20. 1983: MORE OPENNESS-AND LESS...

- 21. 1984: EQUITABLE EMPLOYMENT

- 22. 1988: THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION

- 23. 1989: PUBLIC SERVICE 2000

- 24. 1994: TOUGH CHOICES

- 25. 1996: GETTING GOVERNMENT RIGHT

- 26. 1996: VALUING VALUES

- 27. 1997: THE THREE Rs

- 28. 1998: CITIZENS FIRST

- 29. 2000: SERVING THE PUBLIC GOOD-WHAT'S NEXT?

The Treasury Board is pleased to launch its Millennium Project entitled

Milestones to the Millennium: Serving the Public Good. This publication gives a

chronological account of key events and individuals that have shaped the Public

Service from 1867 to the year 2000.

The Treasury Board is pleased to launch its Millennium Project entitled

Milestones to the Millennium: Serving the Public Good. This publication gives a

chronological account of key events and individuals that have shaped the Public

Service from 1867 to the year 2000.

Milestones to the Millennium was researched and written by Dr. Kenneth Kernaghan, Professor of Political Science and Management at Brock University. In 1996 Dr. Kernaghan received the Vanier Gold Medal for his distinguished contribution to the field of public administration and the Brock University Award for Distinguished Research and Creative Activity. In 1998 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

"Public service is a special calling....Those who devote themselves to it find meaning and satisfaction that are not to be found elsewhere. But the rewards are not material....They are the intangible rewards that proceed from the sense of devoting one's life to the service of the country, to the affairs of state, to public purposes, great or small, and to the public good."(1)

- Deputy Ministers' Task Force on Public Service Values and Ethics, 1997

This Web site provides highlights of the story of the federal Public Service as it has pursued the public good from the time of Confederation to the new millennium. These highlights are shown below in italics and in bold type.

This Web site is a millennium project of Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

1. 1867: LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS

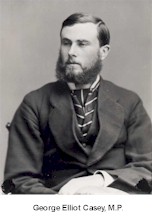

"No matter how excellent might be the

Government of the day, or how wise its administrative acts, it might be spoilt

by the faults of the Civil Service."2 .With

these words, George Elliot Casey, head of the 1877 parliamentary committee on

the Public Service, recognized the central importance of Canada's public service

employees to successful governance. Casey's call to create an efficient Public

Service echoed that of the 1868 Royal Commission on the Civil Service and

foreshadowed the recommendations of five subsequent commissions between 1881 and

1913. Indeed, the dominant issue from Confederation in 1867 until the Civil

Service Act of 1918 was the extent to which government appointments should be

based on merit (fitness for the job) as opposed to patronage (support for a

political party). The report of an 1891-92 inquiry recommended a merit-based

public service so that "the service will become attractive to many persons

who now seek other avenues of employment, and in general the title of public

servant will be an honour to be coveted."3

During its first 50 years, Canada's Public Service made progress, in varying

degrees, towards eliminating patronage, controlling government expenditures and

promoting merit, competitive examinations, a superannuation system and a career

public service.

"No matter how excellent might be the

Government of the day, or how wise its administrative acts, it might be spoilt

by the faults of the Civil Service."2 .With

these words, George Elliot Casey, head of the 1877 parliamentary committee on

the Public Service, recognized the central importance of Canada's public service

employees to successful governance. Casey's call to create an efficient Public

Service echoed that of the 1868 Royal Commission on the Civil Service and

foreshadowed the recommendations of five subsequent commissions between 1881 and

1913. Indeed, the dominant issue from Confederation in 1867 until the Civil

Service Act of 1918 was the extent to which government appointments should be

based on merit (fitness for the job) as opposed to patronage (support for a

political party). The report of an 1891-92 inquiry recommended a merit-based

public service so that "the service will become attractive to many persons

who now seek other avenues of employment, and in general the title of public

servant will be an honour to be coveted."3

During its first 50 years, Canada's Public Service made progress, in varying

degrees, towards eliminating patronage, controlling government expenditures and

promoting merit, competitive examinations, a superannuation system and a career

public service.

In 1918, a federal public service employee working in Montreal walked into a Liberal campaign rally and shouted "Hurrah for the Conservatives." He then went across the street to a Conservative rally and shouted "Hurrah for the Liberals." He was, as a result, dismissed from the Public Service for involvement in partisan politics-even though one could argue that he had been scrupulously equal in his support for the two parties. The Civil Service Act of 1918-a landmark event in the evolution of the federal Public Service-imposed draconian limits on the political activity of public service employees. The Act aimed to promote Public Service efficiency by reducing patronage appointments. The Act also established the Civil Service Commission (now the Public Service Commission), giving it responsibility for such critical functions as staffing and organizing the Public Service, and classifying public service positions. Especially notable was the commission's responsibility to promote merit and reduce patronage by requiring that appointments be determined by competitive examination.

Other times, other customs. In 1921, married women were officially restricted from public service employment-unless they were self-supporting and unless qualified male candidates were not available. Married women who held permanent public service jobs were actually required to resign. These government measures reflected the anti-female bias in the workforce as a whole at this time. According to Kathleen Archibald in her 1970 report, Sex and the Public Service, the Civil Service Commission "perceived its problem not as one of keeping women down-that was taken for granted-but as one of keeping down the number of women in the civil service."4 In practice, it was necessary to hire some married women-but primarily as typists, stenographers and clerks. During the Second World War, a large number of both married and unmarried women were appointed. However, the restrictions against married women were renewed after the war, in part to make room for returning veterans. In recognition of the meritorious performance of married women employees, some departments resisted pressure to remove them. Fortunately, due to the labour shortage arising from the unexpected post-war economic boom, the restrictions were abolished in 1955. As explained later, the issue of female participation in the Public Service arose again in the late 1960s.

All seven of the 1868-1913 inquiries on the Public Service favoured a superannuation (pension) system for public service employees. Sir George Murray, head of the 1913 inquiry, argued that a "system of securing retirement is absolutely essential if the Public Service is to be maintained in a satisfactory condition."5 The Civil Service Commission noted that "the advantages of superannuation in the public interest are apparent" because "it relieves the Government of the embarrassment and extravagance of retaining the services of officers who have outlived their usefulness." The system also "deters efficient officers from leaving the Public Service for private employment...helps to attract a better class of applicants...and in general tends to promote efficiency in every way."6 The 1924 Civil Service Superannuation Act, which provided for retirement allowances, encouraged public service employees to view their employment as a career. By the early 1960s, a royal commission was able to conclude that the provision of pensions was "the biggest attraction of the public service." Moreover, security of tenure was described as "generally better in government service than elsewhere."7 In the 1990s, however, the notion of a career public service in the sense of guaranteed permanent employment came into serious question.

The 1931 Consolidated Revenue and Audit Act created the office of Comptroller of the Treasury. That year, government expenditures were $450 million and revenues were $335 million, for a deficit of $115 million. A large part of the comptroller's job involved protecting two fundamental principles of our parliamentary democracy: that government should spend no money that has not been authorized by Parliament and that money should be spent only for purposes authorized by Parliament. Also in the early '30s, the Treasury Board (a Cabinet committee created in 1869) began to play a more active role in expenditure control. W.C. Ronson, the Secretary of the Board at that time, became known as the "Abominable No Man" for his efforts to cut spending. In 1969, as part of the emphasis on letting managers manage, the comptroller's office was abolished, and its function of certifying and authorizing government expenditures was delegated to departments. In the 1970s, concern about government overspending led to the 1978 creation of an office with a similar name but a different function. The new office-that of Comptroller General-reported to Treasury Board on program evaluation and on financial management and internal audit in government departments.

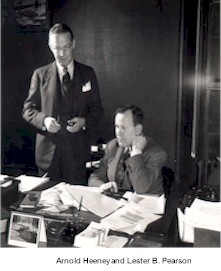

6. 1940: LEADING THE PUBLIC SERVICE

"The

Prime Minister's Office is partisan, politically oriented, yet operationally

sensitive. The Privy Council Office is non-partisan, operationally oriented, yet

politically sensitive."8 That is how in

1971 Gordon Robertson, then Clerk of the Privy Council and the Secretary to the

Cabinet, distinguished the office he headed from the office serving the partisan

political needs of the Prime Minister. Canada's first Clerk of the Privy Council

was appointed on July 1, 1867, the same day on which the country's first

Cabinet ministers were sworn in. By the beginning of the Second World War, the

heavy burden of Cabinet responsibilities called for improved staff assistance.

So in 1940, A.D.P. Heeney, who had been Principal Secretary in the Prime

Minister's Office since 1938, was appointed both as Clerk of the Privy Council

and as the first Secretary to the Cabinet-a dual position since held by some of

Canada's most distinguished public service employees. The person holding this

office was described in 1956 as taking "precedence as the first of the

chief officers of the Public Service."9 The

primacy of this chief officer was formally recognized in 1992, when the Public

Service Reform Act provided that the "Clerk of the Privy Council and the

Secretary to the Cabinet is the Head of the Public Service."10

"The

Prime Minister's Office is partisan, politically oriented, yet operationally

sensitive. The Privy Council Office is non-partisan, operationally oriented, yet

politically sensitive."8 That is how in

1971 Gordon Robertson, then Clerk of the Privy Council and the Secretary to the

Cabinet, distinguished the office he headed from the office serving the partisan

political needs of the Prime Minister. Canada's first Clerk of the Privy Council

was appointed on July 1, 1867, the same day on which the country's first

Cabinet ministers were sworn in. By the beginning of the Second World War, the

heavy burden of Cabinet responsibilities called for improved staff assistance.

So in 1940, A.D.P. Heeney, who had been Principal Secretary in the Prime

Minister's Office since 1938, was appointed both as Clerk of the Privy Council

and as the first Secretary to the Cabinet-a dual position since held by some of

Canada's most distinguished public service employees. The person holding this

office was described in 1956 as taking "precedence as the first of the

chief officers of the Public Service."9 The

primacy of this chief officer was formally recognized in 1992, when the Public

Service Reform Act provided that the "Clerk of the Privy Council and the

Secretary to the Cabinet is the Head of the Public Service."10

7. 1951: CONTROLLING EXPENDITURES

"Major

milestones in the effort of parliament to establish...effective control over

government expenditures."11 This was the

view of Herbert Balls, a long-time Comptroller of the Treasury, about two

events: the 1931 passing of the Consolidated Revenue and Audit Act (discussed

above) and its replacement by the 1951 Financial Administration Act. This 1951

statute delegated to the Treasury Board the authority to make final decisions on

a broad range of financial and personnel matters, including the authority to

approve contracts. In practice, much of the work of this committee of ministers

was delegated to public service employees. This change relieved busy Cabinet

ministers of a heavy burden of routine administrative work.

"Major

milestones in the effort of parliament to establish...effective control over

government expenditures."11 This was the

view of Herbert Balls, a long-time Comptroller of the Treasury, about two

events: the 1931 passing of the Consolidated Revenue and Audit Act (discussed

above) and its replacement by the 1951 Financial Administration Act. This 1951

statute delegated to the Treasury Board the authority to make final decisions on

a broad range of financial and personnel matters, including the authority to

approve contracts. In practice, much of the work of this committee of ministers

was delegated to public service employees. This change relieved busy Cabinet

ministers of a heavy burden of routine administrative work.

The 1951 Act also dealt with the large number of non-departmental organizations that had been created somewhat haphazardly since Confederation to deal with the government's growing workload. These "structural heretics" were found in "a bewildering variety of organizational containers"12 and included hundreds of agencies, boards and commissions enjoying varying degrees of independence from direct ministerial control. The Act tried to clarify the nature of these agencies-and to enhance their accountability-by classifying them as various types of "Crown corporations."

8. 1961: PROTECTING MERIT AND MANAGING PEOPLE

What division of personnel functions among the Public Service Commission, the Treasury Board and government departments best serves the public interest? Various answers have been given to this question. The 1946 Royal Commission on Administrative Classification13 (the Gordon Commission) recommended that the Civil Service Commission be kept as an "independent and separately constituted body" with its tasks confined largely to recruitment and promotion. The Treasury Board would be in charge of the remaining functions of central personnel management. Then, in 1958, the Civil Service Commission released a report, Personnel Administration in the Public Service (the Heeney report).14 This document recommended that the Commission continue to perform recruitment and promotion functions but, in the interest of "unfettered departmental management," give up those functions not directly related to the merit principle. However, the 1961 Civil Service Act confirmed the independence of the Commission, its authority over recruitment and promotion, and its responsibility for certain matters not directly related to merit. A sign of things to come was provision that staff associations should be consulted on pay and other terms and conditions of employment.

9. 1962: LETTING MANAGERS MANAGE

By 1962 there were about half a million federal public service employees performing a remarkable variety of jobs, ranging "from actuaries and anthropologists through bee keepers...and pharmacists, to veterinarians and X-ray operators. An element of mystery is created by the listing of such intriguing operations as insect sampling and rearing aides ... and strippers and layouters."15

To manage all of these activities, it was increasingly suggested that "government should be run more like a business." This view influenced the report of the 1962 Royal Commission on Government Organization headed by J. Grant Glassco, a businessman. While the report recognized the major differences between government and business, and the "first class performance" of certain government operations, it concluded that in many cases "government operations can be improved by adopting methods that have proved effective in the private sector."16 This was a frequently recurring theme in subsequent years, especially in the 1990s.

The Commission's five-volume report had an enormous impact on the organization and management of government. To let managers manage, the report suggested that the Civil Service Commission and the Treasury Board remove some of the constraints they had imposed on departments. The report also proposed that the management functions of the Commission be transferred to the Board.

10. 1967: STRIKING DEVELOPMENTS

In 1967, two new statutes and an amended one greatly affected the relationship

between the Commission and the Board. The Public Service Staff Relations Act,

which gave public service employees the right to bargain collectively, including

the right to strike, had substantial long-term implications. Public service

unions such as the Public Service Alliance of Canada and the Professional

Institute of the Public Service vigorously defended their members' interests. By

the late 1990s, public sector employees (at all levels of government) made up

about one quarter of the labour force but almost one half of all unionized

workers. The Public Service Staff Relations Board was created in 1967 to

administer the federal collective bargaining system and the Treasury Board was

given the responsibility of representing the government in its bargaining

relationship with government employees.

In 1967, two new statutes and an amended one greatly affected the relationship

between the Commission and the Board. The Public Service Staff Relations Act,

which gave public service employees the right to bargain collectively, including

the right to strike, had substantial long-term implications. Public service

unions such as the Public Service Alliance of Canada and the Professional

Institute of the Public Service vigorously defended their members' interests. By

the late 1990s, public sector employees (at all levels of government) made up

about one quarter of the labour force but almost one half of all unionized

workers. The Public Service Staff Relations Board was created in 1967 to

administer the federal collective bargaining system and the Treasury Board was

given the responsibility of representing the government in its bargaining

relationship with government employees.

Another statute-the Public Service Employment Act-gave the Public Service Commission (previously the Civil Service Commission) exclusive authority to appoint and promote public service employees on the basis of merit and to manage such matters as dismissals and political partisanship. The Act also liberalized the long-standing restrictions on the political activity of public service employees imposed by the 1918 Civil Service Act. And an amendment to the Financial Administration Act (discussed earlier) gave the Treasury Board authority over personnel management in the Public Service, including the authority to determine terms and conditions of employment. The administrative unit serving the Board became known as Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

11. 1968: DECISIONS, DECISIONS

The Glassco Commission recognized that

public service employees are "participants in the exercise of power, rather

than mere instruments through which it is wielded by ministers."17

In part, senior public service employees exercise their power by advising

ministers on decisions made by Cabinet and its committees. In 1968, Prime

Minister Lester Pearson formalized the Cabinet committee system by replacing an

ad hoc system with standing committees so as to promote "thorough

consideration of policies, co-ordination of government action, and timely

decisions...."18 He also set up the

Cabinet Committee on Priorities and Planning to determine the government's

priorities as a framework for decisions on spending. In that same year, the new

Prime Minister, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, modified the system to permit

Cabinet committees to make certain decisions on their own. These reforms

strengthened the role of the Privy Council Office (composed of public service

employees), which supplies both policy advice and administrative support to

Cabinet and its committees.

The Glassco Commission recognized that

public service employees are "participants in the exercise of power, rather

than mere instruments through which it is wielded by ministers."17

In part, senior public service employees exercise their power by advising

ministers on decisions made by Cabinet and its committees. In 1968, Prime

Minister Lester Pearson formalized the Cabinet committee system by replacing an

ad hoc system with standing committees so as to promote "thorough

consideration of policies, co-ordination of government action, and timely

decisions...."18 He also set up the

Cabinet Committee on Priorities and Planning to determine the government's

priorities as a framework for decisions on spending. In that same year, the new

Prime Minister, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, modified the system to permit

Cabinet committees to make certain decisions on their own. These reforms

strengthened the role of the Privy Council Office (composed of public service

employees), which supplies both policy advice and administrative support to

Cabinet and its committees.

Subsequent prime ministers redesigned the committee system in a variety of ways to foster the best policy and expenditure decisions and to exercise political control over the Public Service. Effective political control over several hundred thousand employees by a relatively minuscule number of ministers is, of course, an impossible dream. Thus, ministers rely for assistance on other mechanisms, including "central agencies" such as the Privy Council Office and Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

12. 1969: LINKING PROGRAMS AND BUDGETS

Central agencies-especially Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat-were important actors in the next milestone: the introduction in 1969 of program budgeting, known in the federal sphere as the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS). In essence, program budgeting is a form of budgeting that allocates money by program (such as ice-breaking services or old age security) and tries to measure the impact of expenditures on achieving program objectives. PPBS also required a projection of the future cost of programs, because a new program might be inexpensive in its first year but very expensive over time. While PPBS had a lasting impact on budgetary styles by emphasizing the outputs resulting from expenditures of public money, it "was probably unrealistic to think that it could ever live up to its promise to turn budget making into a totally rational process."19

It is evident that government budgeting styles are very much a product of the economic times. For example, the Policy and Expenditure Management System (PEMS), introduced in 1979, set policy priorities and spending limits before Cabinet committees made decisions on program expenditures. And the 1995 Expenditure Management System is a form of program budgeting that emphasizes steady debt and deficit reduction; commitment to a more open, consultative and regular budget process; and improved reporting and accountability to Parliament and Canadians.20

"Saturation psychosis." That

is how a senior public service employee described the cumulative impact on the

Public Service of several major milestones in the late 1960s. These milestones

included not only the Glassco Commission, collective bargaining and the enhanced

role of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, but also the movement towards

a bilingual Public Service.21 Partly in

response to the Glassco Commission's concern about the under-representation of

Francophones in the Public Service, Prime Minister Pearson said in 1966 that

henceforth "the linguistic and cultural values of the English-speaking and

French-speaking Canadians will be reflected through civil service recruitment

and training."22 Then, the 1967 Royal

Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism strongly recommended increased

Francophone representation in the Public Service. Under the 1969 Official

Languages Act, the Treasury Board created the first official languages program.

It was designed to help the Public Service provide services in both official

languages, enable public service employees to work in the official language of

their choice, and achieve full participation in the Public Service by both

Anglophones and Francophones.

"Saturation psychosis." That

is how a senior public service employee described the cumulative impact on the

Public Service of several major milestones in the late 1960s. These milestones

included not only the Glassco Commission, collective bargaining and the enhanced

role of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, but also the movement towards

a bilingual Public Service.21 Partly in

response to the Glassco Commission's concern about the under-representation of

Francophones in the Public Service, Prime Minister Pearson said in 1966 that

henceforth "the linguistic and cultural values of the English-speaking and

French-speaking Canadians will be reflected through civil service recruitment

and training."22 Then, the 1967 Royal

Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism strongly recommended increased

Francophone representation in the Public Service. Under the 1969 Official

Languages Act, the Treasury Board created the first official languages program.

It was designed to help the Public Service provide services in both official

languages, enable public service employees to work in the official language of

their choice, and achieve full participation in the Public Service by both

Anglophones and Francophones.

14. 1970: WOMEN AND THE PUBLIC SERVICE

By 1970, women made up 29 percent of the Public

Service-about the same proportion as their representation in the total labour

force. However, they held only 14 percent of the officer positions. The 1970

Royal Commission on the Status of Women concluded that women did not have equal

opportunity to be appointed to the Public Service and to advance afterwards. The

Office of Equal Opportunities for Women, which the Public Service Commission

created in 1971, was the first of many initiatives to increase the number and

status of female public service employees. By 1990, women made up almost 44

percent of the Public Service. That year, the Task Force on Barriers to Women in

the Public Service23 reported that considerable

progress had been made but significant obstacles to recruiting and retaining

women still existed. By 1999, women made up more than 50 percent of the

Public Service and held 27 percent of the top management positions.

By 1970, women made up 29 percent of the Public

Service-about the same proportion as their representation in the total labour

force. However, they held only 14 percent of the officer positions. The 1970

Royal Commission on the Status of Women concluded that women did not have equal

opportunity to be appointed to the Public Service and to advance afterwards. The

Office of Equal Opportunities for Women, which the Public Service Commission

created in 1971, was the first of many initiatives to increase the number and

status of female public service employees. By 1990, women made up almost 44

percent of the Public Service. That year, the Task Force on Barriers to Women in

the Public Service23 reported that considerable

progress had been made but significant obstacles to recruiting and retaining

women still existed. By 1999, women made up more than 50 percent of the

Public Service and held 27 percent of the top management positions.

15. 1977: SHRINKING THE PUBLIC SERVICE

How can the representation of women be increased when the overall size of the Public Service is being reduced? With great difficulty. The number of federal public service employees peaked in 1977 and has declined considerably since then. In 1999, almost half a million people worked for the federal government; this figure includes those working in departments, public enterprises, the armed forces and the RCMP. A little over 40 percent of these employees, primarily those in regular departments, fell under the jurisdiction of the Public Service Commission. Their number fell from 282,788 in 1977 to 187,187 in 1998-a drop of more than 30 percent. This dramatic decrease in the number of federal public service employees accompanied a series of cost-cutting, downsizing and restructuring measures in the 1980s and early 1990s, including the 1994 Program Review exercise (discussed later).

16. 1977: HARDENING OF THE AUDITORS

"Auditor-general

seeks greater accountability." This newspaper headline24

expresses succinctly the primary role of the office of the Auditor General of

Canada (an independent officer of Parliament first appointed in 1878). One of

the office's most influential declarations came in 1976 amid increasing public

concern about the growing federal deficit. The Auditor General at the time noted

that "the current state of financial administration...is not now adequate

to ensure full and certain control over and accountability for public funds

required for the expanded responsibilities and programmes that now exist."25

In 1977, a separate Auditor General Act authorized the Auditor General to report

on all of "the three Es"-that is, not just on the economy and

efficiency of government expenditures, but also on measures in place to promote

effectiveness. This is the essence of "comprehensive auditing." The

Auditor General demonstrated the office's expanded role throughout the 1990s, in

part by issuing public reports on the government's reform initiatives.

"Auditor-general

seeks greater accountability." This newspaper headline24

expresses succinctly the primary role of the office of the Auditor General of

Canada (an independent officer of Parliament first appointed in 1878). One of

the office's most influential declarations came in 1976 amid increasing public

concern about the growing federal deficit. The Auditor General at the time noted

that "the current state of financial administration...is not now adequate

to ensure full and certain control over and accountability for public funds

required for the expanded responsibilities and programmes that now exist."25

In 1977, a separate Auditor General Act authorized the Auditor General to report

on all of "the three Es"-that is, not just on the economy and

efficiency of government expenditures, but also on measures in place to promote

effectiveness. This is the essence of "comprehensive auditing." The

Auditor General demonstrated the office's expanded role throughout the 1990s, in

part by issuing public reports on the government's reform initiatives.

17. 1979: MAKING MANAGERS MANAGE

An important source of reform initiatives was the 1979 report of the Royal Commission on Financial Management and Accountability (the Lambert Commission). The creation of the Commission in 1976 showed that the government shared the Auditor General's concern about effective control of the public purse in the face of "unprecedented demands placed on government"26 by the public. The Commission recognized the "saturation psychosis" that can result from reform overload in its observation that reforming the Public Service can be "like operating for an appendectomy on a man carrying a piano upstairs."27 After describing Parliament as "the beginning and end of accountability," the Commission recommended several measures to strengthen parliamentary control over government expenditures. In addition, the Commission went beyond the 1962 Glassco Commission's suggestion to "let the managers manage" to argue that "the managers of government...should be required to manage (their responsibilities) in a way that will best serve the public interest."28 The Commission revisited the division of responsibilities between Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and the Public Service Commission. It recommended that the Public Service Commission's responsibilities for personnel management be transferred to the Secretariat and that the Commission focus on its role as guardian of the merit principle. The D'Avignon Committee (discussed next) made a similar recommendation.

18. 1979: WHAT ABOUT THE PEOPLE?

The Lambert Commission, despite its primary emphasis on financial matters, argued that "the management of personnel...is as important as, if not more important than, financial management in achieving effective overall management of government activities."29 The government's recognition of this argument led to the creation of the D'Avignon Special Committee on Personnel Management and the Merit Principle, which also reported in 1979. The Committee argued that the merit principle must be balanced with other principles, such as efficiency, effectiveness, representativeness and equity. It also called for the rejection of "authoritarian, non-participative, uncommunicative and centralized systems" of management and the adoption of "a flexible, entrepreneurial, professional and participative style of management"30 with an emphasis on the results achieved rather than on the way things were done. This latter emphasis became very popular in public management circles a decade later. The Committee also recognized the importance of values-based behaviour in the Public Service-an emphasis that took root in the mid-1980s and came into full bloom in the mid-1990s (as explained below). Like the Lambert Commission, the D'Avignon Committee recommended that the Public Service Commission focus on protecting the merit principle. The Commission "would act as the guardian against political interference in personnel administration and determine whether an employee should be permitted to take part in political activity.31

19. 1982: "CHARTERING" THE PUBLIC SERVICE

The 1967 restrictions on political activity by public

service employees were successfully challenged under the Canadian Charter of

Rights and Freedoms, enacted in 1982. Indeed, in its focus on protecting

individual rights, the Charter has huge implications for the Public Service as a

whole. Public service employees must ensure that statutes and regulations, and

all of their own decisions, are compatible with the Charter's guarantees.

Certain sections of the Charter are especially important for the Public Service.

Section 7, for example, guarantees that "everyone has the right to life,

liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof

except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice." Under

this section, in the celebrated Singh case,32

the Supreme Court required that refugee claimants be given an oral hearing.

The 1967 restrictions on political activity by public

service employees were successfully challenged under the Canadian Charter of

Rights and Freedoms, enacted in 1982. Indeed, in its focus on protecting

individual rights, the Charter has huge implications for the Public Service as a

whole. Public service employees must ensure that statutes and regulations, and

all of their own decisions, are compatible with the Charter's guarantees.

Certain sections of the Charter are especially important for the Public Service.

Section 7, for example, guarantees that "everyone has the right to life,

liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof

except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice." Under

this section, in the celebrated Singh case,32

the Supreme Court required that refugee claimants be given an oral hearing.

20. 1983: MORE OPENNESS-AND LESS...

In an episode of the

television comedy "Yes Minister," a senior public service employee

explains that open government "is a contradiction in terms. You can be

open-or you can have government."33 He is

referring to the fact that public access to government information often makes

life more difficult for politicians and public service employees. Nevertheless,

the purpose of the 1983 Access to Information Act34

was to make government information available to the public and to ensure that

exceptions to this disclosure principle were limited. The implementation of the

Act is part of a broad emphasis in Canada's political culture on transparency.

However, in this information age, there is at the same time greatly increased

public concern about individual privacy. The 1983 Privacy Act35

limits access to personal information about individuals that is contained in

government records and sets out fair information practices to ensure, for

example, that government does not collect personal information it does not need.

In an episode of the

television comedy "Yes Minister," a senior public service employee

explains that open government "is a contradiction in terms. You can be

open-or you can have government."33 He is

referring to the fact that public access to government information often makes

life more difficult for politicians and public service employees. Nevertheless,

the purpose of the 1983 Access to Information Act34

was to make government information available to the public and to ensure that

exceptions to this disclosure principle were limited. The implementation of the

Act is part of a broad emphasis in Canada's political culture on transparency.

However, in this information age, there is at the same time greatly increased

public concern about individual privacy. The 1983 Privacy Act35

limits access to personal information about individuals that is contained in

government records and sets out fair information practices to ensure, for

example, that government does not collect personal information it does not need.

21. 1984: EQUITABLE EMPLOYMENT

Section 15 of the Charter states that "every individual is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection of the law...without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age, or mental or physical disability." This section did not come into force until 1985, the year after the reports of the Royal Commission on Equality in Employment36 (the Abella Commission) and of the parliamentary committee on visible minorities37 were issued, and one year before the federal Employment Equity Act38 came into force. The Charter provided a solid legal foundation for remedying the under-representation in the Public Service of certain historically disadvantaged groups, namely women, Aboriginal persons, disabled persons and persons in a visible minority. Table 1 shows the representation of these designated groups in top management positions, in the Public Service as a whole and as a percentage of their availability in the labour force.

Table 1: Distribution of Public Service Employees by Designated Group and Work Force Availability as of March 31, 199939

|

|

Aboriginal |

Persons with |

Persons in a |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

% |

% |

% |

% |

|

| In Executive Group |

|

|

|

|

| In Public Service as a Whole |

|

|

|

|

| Availability in Work Force |

|

|

|

|

To build on the progress made so far, the Task Force on an Inclusive Public Service was established in 1998 "to achieve a federal Public Service which is representative of the population it serves" and which "values people and values their diversity."40 As well, the Task Force on the Participation of Visible Minorities in the Federal Public Service was created to address the issue of under-representation of visible minority Canadians in the federal Public Service. The Task Force released its report, Embracing Change, in March 2000.41 The Government endorsed the report in June 2000.

22. 1988: THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION

The Canadian Centre for Management Development (CCMD),

established in 1988, has been a constant contributor to the Public Service of

Canada becoming a learning organization. It provides learning opportunities for

current and future public service managers. CCMD's focus on learning, as opposed

to simply training and development, is in keeping with the present emphasis in

public organizations on improving their performance and promoting innovation

through individual and organizational learning. A CCMD report argues that these

two forms of learning are closely related. "Individual learning is the

condition for organizational learning since only individuals have minds that can

learn. But organizations shape and mould the individuals in them: they help them

to learn or prevent them from doing so....Organizational learning has much to do

with overcoming these negative patterns, and turning our places of work into the

kinds of organizations that allow our better selves to emerge and flower."42

While organizational learning is only one way to build innovative public

organizations, it is an increasingly important way.

The Canadian Centre for Management Development (CCMD),

established in 1988, has been a constant contributor to the Public Service of

Canada becoming a learning organization. It provides learning opportunities for

current and future public service managers. CCMD's focus on learning, as opposed

to simply training and development, is in keeping with the present emphasis in

public organizations on improving their performance and promoting innovation

through individual and organizational learning. A CCMD report argues that these

two forms of learning are closely related. "Individual learning is the

condition for organizational learning since only individuals have minds that can

learn. But organizations shape and mould the individuals in them: they help them

to learn or prevent them from doing so....Organizational learning has much to do

with overcoming these negative patterns, and turning our places of work into the

kinds of organizations that allow our better selves to emerge and flower."42

While organizational learning is only one way to build innovative public

organizations, it is an increasingly important way.

Innovation in public organizations was also a major theme of PS 2000, a government initiative officially known as Public Service 2000. Unlike the relatively short-run challenges of the Y2K computer snafu, the Public Service in the new millennium will be faced with huge long-term challenges. These will include global economic competition, heavy public demands on government, the ageing of the labour force, the effects of information technology, and the increased need for knowledge workers. The primary emphases of the PS 2000 Report43 (released in 1990) were service, innovation, people and accountability. Service to the public was to be greatly improved, in part through innovative approaches to management and organization. In support of its assertion that the "members of the Public Service will be treated as its most important resource," the report made suggestions to improve career opportunities, public service labour relations, and employment equity. Finally, public service employees were to be held more accountable for the results they achieved rather than the way they did things - an emphasis suggested a decade earlier by the D'Avignon Committee (discussed above). A major outcome of PS 2000 was the 1992 Public Service Reform Act, which brought greater flexibility to the management of human resources.

Still other reforms came in the early 1990s in the form of reductions in the number of departments, Cabinet committees, programs and public service employees. Especially notable was the Program Review exercise, launched in early 1994. This was a comprehensive review of all government programs to determine the most efficient and effective way of delivering them. Departments were required to assess their programs in the light of six tests.

- Public Interest: Does the program or area of activity serve the public interest?

- Role of Government: Is there a legitimate and necessary role for the public sector in this area?

- Federalism: Is the current role of the federal government appropriate in this area?

- Partnership: What activities or programs should or could be provided, in whole or in part, by the private or voluntary sector?

- Efficiency and Effectiveness: If this program or activity continues, how could it be improved?

- Affordability: Is the resultant package of activities or programs affordable within the fiscal parameters of government?

Program Review contributed significantly to reducing the federal deficit.

25. 1996: GETTING GOVERNMENT RIGHT

Program Review was a central component of a broad and ambitious reform agenda called Getting Government Right. A 1996 report by that title noted that the federal government was continuing to clarify its roles and responsibilities so as to avoid costly overlap and duplication, focus its resources where national action was required, and engage in partnerships with provinces and the private and voluntary sectors. The report also noted the government's efforts to make government work better by using information technology "to get government closer to citizens," adopting "more responsive and flexible approaches to program delivery," changing "the way government makes decisions" and making government operations more results-based "with a client-centred focus on quality service."44 Among other specific measures, the government adopted or increased its use of alternative forms of service delivery, such as public-private partnerships, privatization, contracting out, user fees and service agencies (such as the Canadian Food Inspection Agency). It also focused on measuring the performance of public organizations and public service employees.

Another important approach to getting government right was to improve the government's policy capacity through the Policy Research Initiative.45 The government recognized that high-quality policy development was essential to deal with such forces as globalization, changing demographics, financial constraints and technological change.

From

the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, a series of events-including the many public

service reforms discussed above-raised questions about the state of public

service values (the enduring beliefs that influence public service employees'

decisions). John Tait, the chairperson of the 1996 Deputy Ministers' Task Force

on Public Service Values and Ethics,46

concluded that "public service renewal must come from within: from values

held consciously and enacted daily, from values rooted deeply in Canada's system

of government, from values that help give the public service confidence about

its purpose and character, from values that help public service employees regain

a sense of public service as a high calling."47

From

the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, a series of events-including the many public

service reforms discussed above-raised questions about the state of public

service values (the enduring beliefs that influence public service employees'

decisions). John Tait, the chairperson of the 1996 Deputy Ministers' Task Force

on Public Service Values and Ethics,46

concluded that "public service renewal must come from within: from values

held consciously and enacted daily, from values rooted deeply in Canada's system

of government, from values that help give the public service confidence about

its purpose and character, from values that help public service employees regain

a sense of public service as a high calling."47

The Task Force explained the difficulty public service employees face in balancing a variety of values, including democratic values (such as the rule of law), ethical values (such as integrity), professional values (such as effectiveness) and people values (such as caring). It also called for a synthesis of traditional values, such as accountability and efficiency, with new or emerging values, such as service and innovation.

In addition, the Task Force reaffirmed the importance in Canada's parliamentary democracy of the doctrine of ministerial responsibility, and it called for a reassertion of non-partisanship and merit as fundamental public service values. The Task Force concluded that while government cannot guarantee a public service career in the sense of lifelong employment, it does need a professional Public Service built on long-term rather than short-term employment. Finally, the Task Force recommended that the government adopt a statement of principles or values that would provide a strong foundation for public service conduct.

Reform, renewal and recognition were central themes in the

creation of La Relève. This was a 1997 initiative led by public service

employees that was designed to attract, retain and motivate a sufficient number

of high-quality employees to cope with government's challenges in the new

millennium. In the words of Jocelyne Bourgon, then Head of the Public Service,

"La Relève is a challenge to build a modern and vibrant institution able

to use fully the talents of its people; a commitment by each and every public

servant to...provide for a modern and vibrant organization; and a duty, as

guardians of the institution, to pass on to our successors an organization of

qualified and committed staff."48

Reform, renewal and recognition were central themes in the

creation of La Relève. This was a 1997 initiative led by public service

employees that was designed to attract, retain and motivate a sufficient number

of high-quality employees to cope with government's challenges in the new

millennium. In the words of Jocelyne Bourgon, then Head of the Public Service,

"La Relève is a challenge to build a modern and vibrant institution able

to use fully the talents of its people; a commitment by each and every public

servant to...provide for a modern and vibrant organization; and a duty, as

guardians of the institution, to pass on to our successors an organization of

qualified and committed staff."48

In June 1998, La Relève was replaced by The Leadership Network-a new organization with responsibility for promoting, developing and supporting networks of leaders at all levels of the Public Service and assisting them in the ongoing challenge of La Relève.

Both La Relève and The Leadership Network have promoted recognition of the contributions of public service employees to Canadian government and society. In March 1997, a committee of deputy ministers began work on revitalizing awards and recognition programs, fostering pride in the Public Service by persons outside government and enhancing public service employees' pride in themselves. Among the resulting initiatives was the creation of the Head of the Public Service Award and, to enhance the public's appreciation of the Public Service, the strengthening of National Public Service Week.

The purpose of many public service reforms has been to improve service delivery and, thereby, to promote a positive public view of the Public Service. But surveys in the late 1990s, especially the 1998 national survey entitled Citizens First, showed that the public's perception of public service employees and public organizations was already more favourable than many public service employees thought. Historically, surveys have painted an unduly negative picture of the Public Service, in part by comparing specific private sector organizations, such as supermarkets and banks, to "government" in general. The Citizens First survey49 compared the quality of specific private sector services to that of specific public sector services such as parks and mail delivery. The survey found that the public ranked the quality of service delivery provided by many public organizations as superior to that provided by many private sector organizations. Thus, the argument that private sector service is inherently superior to public sector service is a fiction.

In addition, the 1981 and 1990 World Value Surveys found that Canada's Public Service is among the most trusted in the world. And a 1996 survey found that 77 percent of federal public service employees think that many members of the general public view them as lazy and uncaring, but only 17 percent of the public actually hold this view.50 Finally, a large survey in 199951 found that 69 percent of federal public service employees strongly agreed or mostly agreed that they were satisfied with their careers in the Public Service, and 86 percent strongly agreed or mostly agreed that they were proud of the work done in their work unit. These were optimistic notes on which to enter the new millennium.

29. 2000: SERVING THE PUBLIC GOOD-WHAT'S NEXT?

While hindsight is an exact science, foresight is an imprecise art, especially

in this time of rapid change. The reforms of the 1990s helped prepare the Public

Service for the challenges of the early years of the new millennium. However,

challenges identified in the PS 2000 report persist and unforeseeable problems

are bound to arise. Among the important questions about the future of the Public

Service are these.

While hindsight is an exact science, foresight is an imprecise art, especially

in this time of rapid change. The reforms of the 1990s helped prepare the Public

Service for the challenges of the early years of the new millennium. However,

challenges identified in the PS 2000 report persist and unforeseeable problems

are bound to arise. Among the important questions about the future of the Public

Service are these.

To what extent will the Public Service become a "borderless" institution-"an institution committed to reducing the barriers to the free flow of ideas and information within and among public sector organizations"?52

To what extent will the Public Service become a continuous learning organization-that is, an organization that is committed, for example, to being innovative and flexible?

To what extent will public service leaders be able to stimulate creativity and innovation?

What will be the implications of "electronic government" for such issues as service delivery and individual privacy?

To what extent will public service employees be able to engage citizens in making and implementing public policy?

To what extent will the Public Service become "inclusive"-a Public Service "that values, embraces and supports the contributions of everyone and creates an environment where everyone can contribute at the top of their game"?53

With how much success will the government be able to measure the performance of public service employees and public organizations?

Solid evidence that the government is dealing with these

questions is contained in Results for Canadians: A Management Framework for

Canadians,54 published in 2000. This agenda for

change in the way departments and agencies deliver their programs and services

emphasizes the importance of focusing on service to citizens, sound public

service values, results and responsible spending.

Solid evidence that the government is dealing with these

questions is contained in Results for Canadians: A Management Framework for

Canadians,54 published in 2000. This agenda for

change in the way departments and agencies deliver their programs and services

emphasizes the importance of focusing on service to citizens, sound public

service values, results and responsible spending.

One thing is certain. To continue to perform well in the future, the Public Service must recruit and retain high-quality employees who are motivated to serve the public good.

1 Privy Council Office, Deputy Ministers' Task

Force on Public Service Values and Ethics, A Solid Foundation

(Ottawa: Privy Council Office, 1997), p. 80.

2 House of Commons, Debates (March 15, 1875), p. 708.

3 Report of the Royal Commission Appointed to

Inquire Into Certain Matters Relating to the Civil Service of Canada,

Sessional Papers (1892), no. 16c, p. 28. Emphasis added.

4 Kathleen Archibald, Sex and the Public Service (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1970), p. 14.

5 Sir George Murray, Report on the Organization

of the Public Service of Canada (Ottawa: King's Printer, 1912),

p. 18.

6 Civil Service Commission, Annual Report (1922), p. xiv.

7 Report of the Royal Commission on Government

Organization (the Glassco Commission) (Ottawa: Queen's Printer,

1965), vol. 1, p. 397.

8 Gordon Robertson, "The Changing Role of

the Privy Council Office," Canadian Public Administration (winter 1971),

vol. 14, p. 506.

9W.E.D. Halliday, "The Privy Council

Office and Cabinet Secretariat," reprinted in J.E. Hodgetts and D.C.

Corbett,

eds., Canadian Public Administration (Toronto: Macmillan, 1960), p. 117.

10Public Service Reform Act, 1992, section 40(1).

11Herbert R. Balls, "Issue Control and

Pre-Audit for Authority: The Functions of the Comptroller of the Treasury,"

Canadian Public Administration (June 1960), vol. 3, p. 118.

12J.E. Hodgetts, The Canadian Public Service (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1973), p. 153.

13 Canada, Royal Commission on Administrative

Classification in the Public Service, Report (Ottawa: King's Printer,

1946).

14 Civil Service Commission, Personnel

Administration in the Public Service: A Review of Civil Service Legislation

(Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1959).

15 Royal Commission on Government Organization, Report (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1962), vol. 1, p. 21.

16 Ibid., (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1963), vol. 5, p. 29.

17 Ibid., p. 74.

18 Office of the Prime Minister, press release (January 20, 1968).

19 Kenneth Kernaghan and David Siegel, Public

Administration in Canada: A Text (Toronto: Nelson, 4th ed. 1999),

p. 628.

20 Government of Canada, The Expenditure

Management System of the Government of Canada (Ottawa: Supply and

Services, 1995), pp. 1-13.

21 H.L. Laframboise, "Administrative

Reform in the Federal Public Service: Signs of a Saturation Psychosis,"

Canadian Public Administration (fall 1971), pp. 303-325.

22 House of Commons, Debates (April 6, 1966), p. 3915.

23 Beneath the Veneer: Report of the Task

Force on Barriers to Women in the Public Service (Ottawa: Minister of

Supply and Services, 1990), 4 vols.

24The Globe and Mail, June 10, 1983, p. B1.

25 Canada, Office of the Auditor General,

Report, 1976 (Ottawa: Supply and Services Canada, 1977), p. 9. Emphasis

added.

26Royal Commission on Financial Management

and Accountability, Final Report (Ottawa: Supply and Services

Canada, 1979), p. 1.

27 Ibid., p. 8.

28 Ibid., p. 33. Emphasis added.

29 Ibid., p. 25. Emphasis added.

30 Canada, Special Committee on the Review of

Personnel Management and the Merit Principle in the Public Service,

Report (Ottawa: Supply and Services, 1979), p. 46.

31 Ibid., p. 223.

32 Singh v. Minister of Employment and Immigration (1985), 17 D.L.R. (4th), 422.

33 Jonathon Lynn and Antony Jay, eds., The Complete Yes Minister (New York: Harper and Row, 1984), p. 21.

34 Canada, Statutes, 1980-1983, c.111, Schedule I.

35 Ibid., Schedule II.

36 Royal Commission on Equality in Employment, Report (Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services, 1984).

37 Canada, House of Commons, Equality Now:

Report of the Special Committee on Participation of Visible Minorities

in Canadian Society (March 8, 1984), no. 4.

38 Revised in 1995. See Canada, Consolidated Statutes (1995, c. 44), chapter E-5.4.

39 Compiled from Treasury Board, Employment

Equity in the Federal Public Service: 1998-99, chapter 2. Available at

http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/report/empequi/ee_99_2-eng.asp.

40 Available at http://leadership.gc.ca/inclusive/focus_e.shtml.

41 Available at http://www.visiblepresence.com/action.

42 Canadian Centre for Management Development,

Continuous Learning: A CCMD Report (Ottawa, Canadian Centre

for Management Development, 1994), p. 5.

43 Public Service 2000, The Renewal of the Public Service of Canada (Ottawa: Privy Council Office, 1990).

44 Privy Council Office, Getting Government Right: A Progress Report (Ottawa: Privy Council Office, 1996), p. 19.

45 Policy Research Initiative. Available at http://policyresearch.schoolnet.ca.

46 Privy Council Office, Deputy Ministers'

Task Force on Public Service Values and Ethics, A Solid Foundation

(Ottawa: Privy Council Office, December 1997).

47 John Tait, "A Strong Foundation:

Report of the Task Force on Public Service Values and Ethics (the

summary),"

Canadian Public Administration (spring 1997), vol. 40, p. 21.

48 Fourth Annual Report to the Prime Minister

on the Public Service of Canada (Ottawa: Privy Council Office,

February 3, 1997), ch. VI, pp. 5-6. Emphasis in original.

49 Erin Research Inc., Citizens First (Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Management Development, 1998), p. 6.

50 Ekos Research Associates, Perception of

Government Service Delivery, Report for Deputy Ministers' Task Force on

Service Delivery Models (Ottawa: Privy Council Office, 1996), pp. 23, 44.

51 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat,

Public Service Employee Survey 1999. Available at http://www.survey-

sondage.gc.

52 Jocelyne Bourgon, Fifth Annual Report to

the Prime Minister on the Public Service of Canada (Ottawa: Privy

Council Office, March 31, 1998), p. 20.

53 Task Force on an Inclusive Public Service. Available at http://leadership.gc.ca/inclusive/whoweare_e.html.

54 Available at

http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/report/res_can/siglist-eng.asp.