ARCHIVED - Canadian Artists and Producers Professional Relations Tribunal

This page has been archived.

This page has been archived.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

2008-09

Departmental Performance Report

Canadian Artists and Producers Professional Relations Tribunal

The original version was signed by

The Honourable Rona Ambrose

Minister of Labour

Table of Contents

Section II – Analysis of Program Activities by Strategic Outcome

Section III – Supplementary Information

Chairperson's Message

I am pleased to present to Parliament and Canadians the Departmental Performance Report of the Canadian Artists and Producers Professional Relations Tribunal for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2009.

The Canadian Artists and Producers Professional Relations Tribunal administers a collective bargaining regime for professional self-employed artists and producers in federal jurisdiction. Under Part II of the Status of the Artist Act, the Tribunal defines sectors of artistic and cultural activity for collective bargaining, certifies artists' associations to represent artists working in those sectors, and deals with complaints of unfair labour practices and other matters brought forward by parties under the Act.

Parliament passed the Status of the Artist Act in 1992 as part of a commitment to recognize and stimulate the contribution of the arts to the cultural, social, economic and political enrichment of the country. The Act reflects the recognition that constructive professional relations in the arts and culture sector are an important element of a vibrant Canadian culture and heritage.

Since its inception, the Tribunal has defined 26 sectors of artistic activity and certified 24 artists' associations to represent them. Certified artists' associations have concluded over 160 scale agreements with producers, including government producers and broadcasting undertaking, since their certification. Over 14 percent of these are the first agreements that the parties have ever concluded.

The Tribunal has a single strategic outcome: constructive professional relations between self-employed artists and producers under its jurisdiction. In working towards its strategic outcome, the Tribunal in the past focused most of its work on certification. Most sectors are now defined, and artists' associations are certified to represent them. The work of the Tribunal is now more related to complaints and determinations, changes in the definition of sectors and in representation, and assisting parties in the bargaining process.

In addition, the Tribunal now places greater emphasis on outreach to its stakeholders and on research to support Tribunal decisions. The Tribunal needs to ensure that the Act is widely known and well understood, and that its services are understood and known by the stakeholder community. It focuses much of its effort on fully informing and assisting artists, artists' associations, and producers of their rights and responsibilities under the Act and of the services that the Tribunal can make available to them.

The Tribunal's outreach role, and the careful disposition of matters brought before it, will help to promote productive professional relations in the cultural sector, and contribute to a thriving Canadian culture.

Elaine Kierans

Acting Chairperson and Chief Executive Officer

Section I – Overview

1.1 Summary Information

Raison d’ętre

Parliament created the Canadian Artists and Producers Professional Relations Tribunal to administer the labour relations provisions of the Status of the Artist Act for self-employed artists and producers in federal jurisdiction. The Tribunal defines sectors of artistic activity for collective bargaining, certifies artists' associations to represent self-employed artists working in those sectors, and deals with matters such as complaints of unfair labour practices from artists, artists' associations and producers. The Tribunal's fulfilment of its mandate contributes to the development of constructive labour relations between artists and producers.

Responsibilities

The Canadian Artists and Producers Professional Relations Tribunal is an independent, quasi-judicial agency that administers Part II of the Status of the Artist Act, which governs professional relations between self-employed artists and federally regulated producers. The Tribunal reports to Parliament through the Minister of Labour. The Minister of Canadian Heritage also has responsibilities pursuant to Part II of the Act.

Labour relations between the vast majority of workers and employers in Canada fall under provincial jurisdiction. Federal jurisdiction over labour relations is limited to a small number of sectors, including broadcasting, telecommunications, banking, interprovincial transportation, and federal government institutions. The Tribunal is one of four federal agencies that regulate labour relations. The other three are the Canada Industrial Relations Board, which deals with labour relations between private sector employers in federal jurisdiction and their employees, the Public Service Labour Relations Board, which deals with labour relations between federal government institutions and their employees, and the Public Service Staffing Tribunal, which deals with complaints from federal public service employees related to internal appointments and lay-offs.

The Tribunal's jurisdiction over producers is set out in the Status of the Artist Act, and covers federal government institutions, including government departments and the majority of federal agencies and Crown corporations (such as the National Film Board and the national museums), and broadcasting undertakings under the jurisdiction of the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission.

The Tribunal's jurisdiction over self-employed artists is also set out in the Status of the Artist Act, and includes artists covered by the Copyright Act (such as writers, photographers, and music composers), performers (such as actors, musicians, and singers), directors, and other professionals who contribute to the creation of a production, such as those doing camera work, lighting and costume design.

The Tribunal has the following statutory responsibilities:

- To define the sectors of cultural activity suitable for collective bargaining between artists' associations and producers,

- To certify artists' associations to represent self-employed artists working in these sectors, and

- To deal with complaints of unfair labour practices and other matters brought forward by artists, artists' associations, and producers, and prescribe appropriate remedies.

Artists' associations certified under the Status of the Artist Act have the exclusive right to negotiate scale agreements with producers. A scale agreement specifies the minimum terms and conditions under which producers engage the services of, or commission a work from, a self-employed artist in a specified sector, as well as other related matters.

The Status of the Artist Act and the Tribunal's regulations, decisions, and reports to Parliament and central agencies can be found on the Tribunal's Web site.

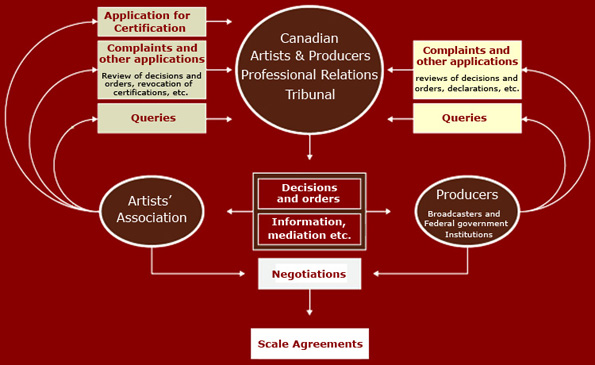

Figure 1 illustrates the Tribunal's responsibilities and the key processes under the Status of the Artist Act, Part II.

Figure 1. Tribunal Responsibilities and Key Processes

STATUS OF THE ARTIST ACT

Under subsection 10(1) of the Status of the Artist Act, the Tribunal is composed of a Chairperson (who is also the chief executive officer), a Vice-chairperson, and not less than two or more than four other full-time or part-time members. Members are appointed by the Governor in Council. Currently, the position of the Chairperson of the Tribunal is vacant, and the Vice-Chairperson acts as the Chairperson. The Tribunal has only one other member at present. Under subsection 13(2) of the Act, three members constitute a quorum for meetings or proceedings of the Tribunal. Both the Vice-chairperson and the member are part-time appointees.

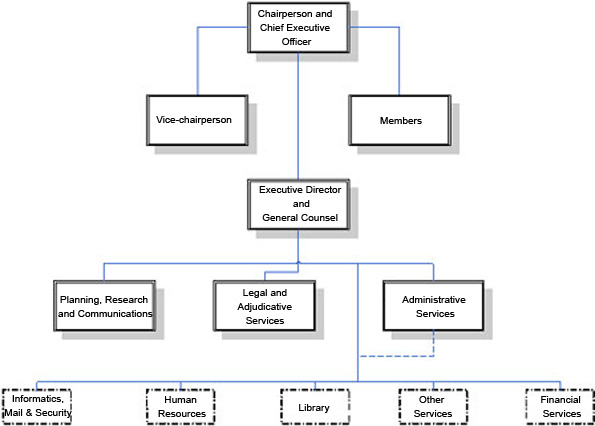

The Executive Director and General Counsel heads the Tribunal Secretariat and reports to the Chairperson. Ten staff members (when the Secretariat is fully staffed) carry out the functions of legal counsel, registrar, planning, research, communications, and administrative services. The Tribunal outsources some standard corporate services that are not required full-time, such as informatics and human resources. Figure 2 illustrates the Tribunal's organizational structure.

Figure 2. Tribunal's organizational structure

Organization Chart

![]() Services provided

on contract or by other arrangements (Please see Section II, Financial Management and Comptrollership,

for more detail)

Services provided

on contract or by other arrangements (Please see Section II, Financial Management and Comptrollership,

for more detail)

The Tribunal administers the following legislation and associated regulations:

| An Act respecting the status of the artist and professional relations between artists and producers in Canada (Short Title: Status of the Artist Act) | S.C. 1992, c.33, as amended |

| Status of the Artist Act Professional Category Regulations | SOR 99/191 |

| Canadian Artists and Producers Professional Relations Tribunal Procedural Regulations | SOR/2003-343 |

Strategic Outcomes

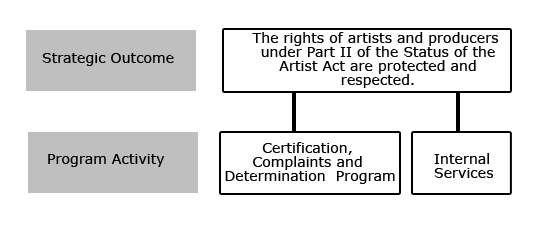

The Tribunal seeks to achieve the following single strategic outcome:

The rights of artists and producers under Part II of the Status of the Artist Act are protected and respected.

Program Activity Architecture

The chart below illustrates the Tribunal's program activities, which contribute to its strategic outcome.

1.2 Performance Summary

| Planned Spending | Total Authorities | Actual Spending |

|---|---|---|

| 1,973 | 2,061 | 1,015 |

| Planned | Actual | Difference |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 7 | 3 |

The Tribunal's spending and human resource levels are relatively stable, as its plans and priorities are generally stable from year to year and involve no major new initiatives. This reflects the strict quasi-judicial adjudicative mandate of the Tribunal, as set out in the Status of the Artist Act.

| Program Activity | 2007-08 Actual Spending |

2008-09 | Alignment to Government of Canada Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Estimates |

Planned Spending |

Total Authorities |

Actual Spending |

|||

| Certification, Determination and Complaints Program |

1,055 | 1,973 | 1,973 | 2,061 | 1,015 | Vibrant Canadian culture and heritage |

| Total | 1,055 | 1,973 | 1,973 | 2,061 | 1,015 | |

Contribution of Priorities to Strategic Outcome

| Operational Priorities | Type | Status | Links to Strategic Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deal with matters brought before the Tribunal with high quality service | Ongoing | Met | Providing high quality service in dealing with applications for certification, review, determination, consent to prosecute, and revocation of certification, and with complaints of unfair practices, ensures that the rights of the parties before the Tribunal are respected and protected. |

| Fully inform and assist stakeholders | Ongoing | Met | In support of its adjudicative function, the Tribunal informs artists and producers about the Status of the Artist Act, in order to permit them to fully exercise their rights and fulfil their responsibilities under the Act. The Tribunal assists the parties in the bargaining process, ensuring that they are fully informed and can take advantage of all the elements of the collective bargaining structure set up under the Act. It provides ready access to information and mediation assistance when parties need it. |

| Management Priorities | Type | Status | Links to Strategic Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improve management practices | Ongoing | Met | In the interest of providing better service to its stakeholders and to Canadians, the Tribunal seeks continuous improvement of its management practices, focusing on implementing the Public Service Modernization Act and the various initiatives of Treasury Board and other central agencies. |

Risk Analysis

The nature of the Tribunal's mandate and business environment makes the organization relatively risk averse. The same observation could be made of any quasi-judicial organization.

The Tribunal has numerous management strategies to mitigate potential risks. Like any administrative tribunal or court, it must be prepared to deal with highs and lows of case volume. Its services must be available to artists and producers as and when the need arises. Its certification work is relatively predictable, since it has certified artists' associations to represent most sectors under its jurisdiction. Complaints under the Act and references from arbitrators are less predictable and can arise at any time.

The economic crisis has begun to affect the arts and culture sector, and the impact is expected to become more severe. If economic problems result in parties having difficulty meeting their obligations under the Act or reaching agreements under it, there may be an increase in demand for the Tribunal's services.

The Tribunal has traditionally been able to manage the unpredictability of caseloads by judicious planning and budgeting within its existing appropriation levels for both human and financial resources. In years where its total appropriations have not been used, it has returned funds to the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

The most important risk to the Tribunal is an insufficient number of members to assure quorum for hearings. The Tribunal, when it lacks quorum, cannot process cases before it.

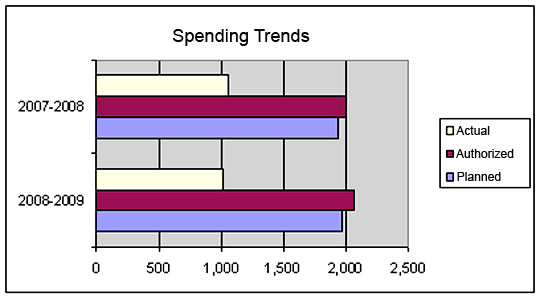

Expenditure Profile

The strict statutory mandate of the Tribunal means that resources are relatively steady from year to year. Planned and authorized spending increased somewhat due to increases in salaries and benefits pursuant to collective agreements signed by Treasury Board that impacted on the salaries of Tribunal employees. In addition, like all government departments, the Tribunal's operating budget carry forward (5 percent of base budget) from 2007-2008 was added to its authorities. The Tribunal plans for likely maximum use of its services but it has no control over its actual case load and level of activity. The Act allows parties to bring cases to the Tribunal but nothing guarantees how many will do so and how often. In short, the Tribunal's caseload is not predictable. Although 2008-2009 actual spending was significantly lower than what had been planned and authorized, it changed only 4 percent from 2007-2008. Like all government departments, the Tribunal returns its unused resources to the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

Summary of Tribunal Performance

Overall Performance

The Tribunal has a single strategic outcome, that the rights of artists, artists' associations and producers under the Status of the Artist Act are protected and respected. Its single program activity, the Certification, Determination and Complaints Program, contributes to this strategic outcome. Its overall performance is equivalent to its "performance by strategic outcome," reported in Section II. As will be seen in Section II, the Tribunal continues to make progress in achieving its strategic outcome.

Operating Environment and Context

The economics of artistic endeavour

Culture and the arts contribute significantly to Canada's economy. According to a 2008 analysis1 by the Conference Board of Canada, the cultural sector generated about $46 billion in real value-added gross domestic product (GDP) in 2007. This constituted 3.8 percent of Canada's real GDP. The cultural sector also created 616,000 jobs.

Moreover, the arts and cultural industries enhance economic performance more generally and act, in the words of the Conference Board, as "a catalyst of prosperity," attracting talent and spurring creativity across all sectors of the economy. The Conference Board analysis found that when the effects on other sectors of the economy were considered, the economic footprint of the arts and cultural industries amounted to about $84.6 billion in 2007, or 7.4 percent of total real GDP, and contributed 1.1 million jobs to the economy.

The earnings of Canadian artists, however, do not reflect their contributions to the country. Findings2 from a study of the 2006 census reveal that artists overall work for near-poverty-level wages, with average annual earnings in 2005 of just $22,731, compared with $36,301 for all Canadian workers – a wage gap of 37 percent. And while average earnings for the overall labour force rose by almost 10 percent from 1990 to 2005, artists' incomes slid by 11 percent.

Besides having lower earnings, many artists are self-employed. In the study referred to above, forty-two percent of the artists analyzed described themselves as self-employed, compared with seven percent of workers in the economy as a whole. While selfemployment has some advantages, self-employed workers do not have advantages typically available to employees, such as employment insurance, training benefits and pension funds. An estimated 135,000 self-employed artists fall under the Tribunal's jurisdiction.

The federal government has various institutions, programs and policies to recognize and support artists and producers. The Status of the Artist Act and the Tribunal are part of the federal support system for Canadian arts and culture.

Limitations of the Status of the Artist Act

The impact of the Act is limited by its application to a small jurisdiction. Most work in the cultural sector, including the bulk of film and television production, sound recording, art exhibitions, theatrical production and book publishing, falls under the jurisdiction of the provinces. To date, Quebec is the only province with legislation granting collective bargaining rights to self-employed artists. The need for provincial legislation was recognized by the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage in its ninth report in 1999, and by the Department of Canadian Heritage in its 2002 evaluation3 of the provisions and operations of the Status of the Artist Act. The Tribunal supports the adoption of collective bargaining legislation for self-employed artists working in provincial jurisdiction, and will continue to provide information to policy makers and others interested in the benefits of such legislation.

The Act's effectiveness is also limited because few federal government institutions – one of the class of producers covered by the Act – have entered into scale agreements with artists' associations. Artists' associations are typically hard-pressed for time and resources, and they would rather negotiate with producers' associations than with individual producers. Similarly, many government producers would prefer to designate one department as their lead negotiator. One of the recommendations from the Department of Canadian Heritage's 2002 evaluation report was that the government consider establishing a single bargaining authority for all departments. The Tribunal supports this recommendation, as it would facilitate the bargaining process and make it more cost-effective.

The Tribunal also supports the recommendation, in the 2002 evaluation, for a number of amendments to the Act, such as adding provisions for arbitration in cases where bargaining has failed to result in a first agreement between a certified artists' association and a producer.

The challenge of operating a small federal agency

Its specific legislation and unique stakeholder base aside, the Tribunal is like any other federal government department: it must exercise care and restraint in the spending of public funds, and provide Parliament and Canadians with transparent and accountable reporting. At its creation in 1993, the Tribunal adopted efficient business practices, with clear statements of objectives, high standards for service delivery, a comprehensive performance measurement framework, and transparent reporting on its activities and results. Its management team embraced this framework at its inception and has been guided by it as it evolves.

As a very small agency, the Tribunal faces a particular operating challenge, with its small staff responsible for a myriad of tasks. This is compounded by the fact that the workload is unpredictable and changing, since parties themselves decide whether to bring cases to the Tribunal. To meet these particular challenges, the Tribunal follows flexible practices such as contracting-out and sharing of accommodation, as described in Section II under "Priority 3: Improve Management Practices."

Section II – Analysis of Program Activities by Strategic Outcome

2.1 Strategic Outcome - The rights of artists and producers under Part II of the Status of the Artist Act are protected and respected.

Part II of the Act, and the collective bargaining regime set up under it, are intended to encourage constructive professional relations between artists and producers in federal jurisdiction. This is the sole strategic outcome under the Tribunal's Program Activity Architecture approved by Treasury Board for 2008-2009.

During fiscal year 2008-2009, the Tribunal pursued three priorities in order to achieve this strategic outcome. It continued to focus on timeliness and fairness in dealing with requests under the legislation. It strengthened its focus on ensuring that stakeholders have timely information about the Act and their rights and responsibilities under it, and about Tribunal decisions and activities. And it continued to improve its management practices, focusing on implementing the Public Service Modernization Act and the various initiatives of Treasury Board and other central agencies.

The performance measurement framework for these priorities matches that presented in the Tribunal's Report on Plans and Priorities for 2008-2009. The performance results are reported below the following table, which summarizes them.

|

Expected Results |

Performance Indicators |

Targets |

Performance Status |

Performance Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fair and timely resolution of cases | Average time to issue reasons for a decision after the hearing in all cases | Maximum of 60 calendar days | Met | Average time to issue reasons after hearing was 3 days4 |

| Average time to process all cases (from date of receipt of completed application to date of decision) | Maximum of 200 calendar days | N/A for fiscal 2008-2009 | Tribunal did not render any final decisions in 2008-2009 due to lack of quorum | |

| Percentage of Tribunal decisions upheld under judicial review | More than 75 percent | N/A for fiscal 2008-2009 | No applications for judicial reviews in 2008-2009. | |

| Availability to stakeholders of information about the Act and the Tribunal | Quality and timeliness of information | Bulletins issued within 60 days of major developments (e.g., Tribunal decisions). | N/A for fiscal 2008-2009 | No major Tribunal decisions or other developments requiring bulletin |

| Responses to inquiries within two working days. | Met | 14 of 15 responses within target | ||

| Responses thorough and correct | N/A for fiscal 2008-2009 | Stakeholders were not systematically surveyed | ||

| Stakeholders are satisfied (as determined by stakeholder consultations) | N/A for fiscal 2008-2009 | Stakeholders were not systematically surveyed | ||

| Quality of the Tribunal's Web site | The Web site contains timely, accurate and helpful information, explains clearly how to do business with the Tribunal, and meets Government On-Line standards. | Met | Website regularly updated, completely overhauled to meet Common Look and Feel (CLF) 2.0 Standards. | |

| Stakeholders are satisfied (as determined by consultations). | N/A for fiscal 2008-2009 | Stakeholders were not systematically surveyed | ||

| Direct contacts with stakeholders | Meetings are held with at least four artists' associations and four producers or producers' associations. Stakeholders are satisfied, as determined in consultation. | Met | Tribunal staff met with 5 artists' associations and 6 producers, as well as 2 producers' associations | |

| Improved management practices | Management Accountability Framework | Required elements of MAF are in place | Met | |

| Human Resources Plan | Plan updated twice per year | Met | ||

| Internal Policies Suite | Policies updated as needed and in line with government's objectives and Treasury Board policies | Met |

Priority 1: Deal with matters brought before the Tribunal with high quality service

High quality in processing of cases includes the work of staff, in preparing cases and providing legal advice, and the work of the Tribunal in issuing decisions.

The level of case activity in 2008-2009 was similar to that in recent years. Certification cases have decreased over the years since the passage of the Status of the Artist Act, with most sectors of artistic activity represented now by certified artists' associations. Increasingly, inquiries and cases brought before the Tribunal concern issues that arise in collective bargaining.

Eleven certifications of artists' associations as sectoral bargaining agents came up for renewal; all eleven were renewed. The Tribunal issued two interim decisions. At year's end, two cases were pending. Details on cases are presented in the Tribunal's annual report and its Information Bulletins, all available on the Tribunal's Website.

The Tribunal's ability to serve its stakeholders was significantly affected by changes in its membership and by a loss of quorum. After September 2008, when it lost quorum, and for the remainder of the fiscal year, the Tribunal was unable to hear cases.

As set out in the 2008-2009 Report on Plans and Priorities, the Tribunal's performance measurement framework looks at timeliness and fairness. These two factors are interrelated but they are distinct and require different performance indicators and measurements.

For timeliness, we use two indicators: the time taken to issue reasons for a decision after a hearing, and the total time taken to process a case, from the date an application is received until the date of the decision. Targets and performance information for these indicators are shown in the table above. Performance information is collected yearly but is also displayed and analyzed over multiple years, in order to identify trends.

The other indicator of timeliness, average time required to process applications, is based on time elapsed from the date of receipt of a completed application to the date of the final decision in the case. This indicator is not applicable for the past fiscal year, as the Tribunal did not render any final decisions due to a lack of quorum.

The Tribunal uses the term "fairness" broadly, to encompass all its responsibilities as a quasi-judicial tribunal, such as impartiality, accessibility, integrity, and confidentiality.

We use as an indicator of fairness the percentage of Tribunal decisions upheld on judicial review. The Federal Court may review a Tribunal decision in the following circumstances:

- if the Tribunal acted without jurisdiction or beyond its jurisdiction, or refused to exercise its jurisdiction;

- if it failed to observe a principle of natural justice, procedural fairness or other procedure that it was required by law to observe; or

- if it acted, or failed to act, by reason of fraud or perjured evidence.

The indicator is not perfect, because parties may be dissatisfied with Tribunal decisions but not seek judicial review, for any number of reasons, including lack of resources. Nonetheless, the Federal Court acts as the arbiter of fairness of federal quasi-judicial tribunals, so this is an important indicator. We have set as a target that more than 75 percent of our cases are upheld on judicial review. As with timeliness, we collect this information yearly but analyze it over longer periods.

To date, only three of the Tribunal's 86 interim and final decisions have been challenged in this manner. Two requests for judicial review were dismissed by the Federal Court of Appeal, one in 1998-1999 and one in 2004-2005. The third request was withdrawn.

An important outcome of fair Tribunal decisions is the development of a solid body of precedents. These can be used to help resolve future cases.

The Tribunal is committed to maintaining and strengthening its research function to support the work of the Tribunal. This is a matter of importance for the Tribunal: it deals continually with new issues, and its jurisprudence is largely innovative, requiring a strong research capacity to ensure that decisions are fair and reflect the realities of the stakeholder community. Tribunal staff continued developing research resources over the course of the fiscal year, meeting with producers and artists' associations and attending industry conferences, and facilitated information and training sessions for Tribunal members on developments in broadcasting and labour relations. The Tribunal's case management database was further developed and refined over the course of the year.

Priority 2: Fully inform and assist stakeholders

The Tribunal's second priority is to fully inform and assist the artists, artists' associations, and producers that make up its stakeholder base. The Tribunal has a duty to ensure that artists, artists' associations and producers are fully aware of their rights and responsibilities under the Status of the Artist Act. For parties to benefit from the Act, for collective bargaining under the Act to take place and for the long-term objectives of the Act to be realized, the parties must fully understand the legislation.

One way that the Tribunal does this is through timely responses to inquiries. The Tribunal receives a wide variety of questions from stakeholders, dealing with subjects like jurisdiction, specifics of the various cultural industries, and how to use the Act. Tribunal staff members respond to these questions quickly and thoroughly, always inviting further comment or question. The Tribunal's target is to respond within 2 working days of the receipt of the inquiry. The Tribunal exceeded its target in 87 percent of its inquiry responses, and fell short of it in less than 1 percent.

The Tribunal is committed to facilitating collective bargaining by making research tools and resources available to artists associations and producers. In June, 2008, Tribunal staff entered into an informal partnership with Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC) to pool efforts to make scale agreements under the Act readily available to stakeholders for research purposes. HRSDC runs a database system known as Negotech that digitally stores collective agreements filed with the Minister of Labour. The Tribunal and HRSDC now work together to ensure that holdings of scale agreements under the Act in the Negotech database are as complete as possible. Shortly after the end of the fiscal year, the Tribunal's website began providing hyperlinks to scale agreements on Negotech.

With respect to more general information needs about the Act and the Tribunal's services and activities, the Tribunal has traditionally used information bulletins, regularly-updated information on its Web site, and information sessions for stakeholders. Follow-up with stakeholders has shown that these are well received and considered useful.

Large-scale information sessions for stakeholders have in recent years given way to more tailored and customized information. The Tribunal's stakeholders have different, often quite specific, needs for information. More focused personalized information and small group or individual meetings are often a more effective way of addressing those needs. The Tribunal emphasized these more direct approaches to stakeholders, including participation in industry conferences that bring stakeholders together and allow multiple meetings and information exchanges, maximizing the effective use of Tribunal staff time. In 2008-2009, Tribunal staff used informal means to increase the knowledge and awareness of the Act and the Tribunal among a cross-section of stakeholders from the artists' and producers' communities, including 5 artists' associations, 6 producers and 2 producers' associations. Both approaches, formal presentations and informal meetings, are useful, and the Tribunal will continue to use them both, as appropriate.

The Tribunal did not issue any information bulletins in 2008-2009. Information bulletins are used to report important developments at the Tribunal or with the Act. There was no major development during that time period.

The Tribunal continued revising its website to make it more helpful and accessible, and made major revisions to the website to bring it into full compliance with the government's new Common Look and Feel (CLF 2.0) standards. The CLF 2.0 compliance conversion was completed on December 31st, 2008, meeting the deadline set by the Treasury Board Secretariat. The website received 35,307 hits in fiscal 2008-2009.

Research to support the Tribunal's work with artists' associations and producers continued to be important in 2008-2009, especially in view of current developments in broadcasting and new media. Broadcasting is one of the principal areas of the Tribunal's jurisdiction, and the challenges of transformations in the broadcasting industry – mergers, changes of ownership, new technologies, and the weakening of traditional business models – for artists' associations and broadcasters require new efforts from the Tribunal to facilitate negotiation under the Act. Research staff monitored and analyzed developments in broadcasting and new media throughout the fiscal year, tracking CRTC and Parliamentary initiatives and attending industry conferences.

Priority 3: Improve management practices

As in previous years, the Tribunal used outsourcing and cost-saving agreements for many services not required on a full-time basis. It contracted with the Department of Canadian Heritage for human resources services, with Industry Canada for security and mail services, and with the Public Service Labour Relations Board for informatics support. It has arrangements with two other federal labour boards to use their hearing rooms and library services. It also contracts for the services of a financial analyst.

The Tribunal Secretariat continued to maximize its human resources, selecting multiskilled, flexible staff capable of handling a wide variety of responsibilities. This matches the economic efficiency of the Tribunal itself: Tribunal members are part-time appointees, called on and paid only as needed, and bilingual, which facilitates scheduling of hearings. The Tribunal continued to provide accommodation and administrative and financial services to Environmental Protection Review Canada, thereby lowering the overall costs to the government.

To improve its operational efficiency and its capability to measure performance, the Tribunal continued to refine its case management database over the course of 2008-2009.

The Tribunal continued to develop its management practices in 2008-2009, working on implementing government-wide initiatives and continuing work on those initiatives already implemented, in a cluster group with three other small quasi-judicial agencies, the Copyright Board, the Registry of the Competition Tribunal, and the Transportation Appeal Tribunal. The cluster group focused on the implementation of the Public Service Modernization Act, and on preparation for the Management Accountability Framework Assessment. The Tribunal also worked with other networks such as the Small Agency Transition Support Team for expertise related to human resources issues (such as the Policy on Learning, Training and Development), and was an active participant in the Micro and Small Agency Labour Management Consultation Committee to ensure adherence to the Public Service Labour Relations Act.

The Tribunal continued to work with and update its Human Resources Plan. It uses this plan to forecast its staffing needs, deal strategically with staffing, retention and succession issues, and mobilize and sustain the energies and talents of its members and employees, enabling them to contribute to the achievement of organizational goals.

The Tribunal has internal policies to promote excellence in performance, accountability, and workplace well-being, and a code of values and ethics as well as policies on harassment and the internal disclosure of wrongdoing. To ensure that these policies remain current and relevant, the Tribunal further refined its policy review and renewal cycle, including continued study and development of evaluation strategies and performance measurement tools.

The Tribunal's human resources and business planning are integrated, and it uses a Strategic Human Resources Plan and a Staffing Management Accountability Framework. In 2008-2009, it continued to monitor staffing actions in relation to its staffing strategies and plans, although the small number of positions and of staffing actions hardly justifies the term "statistics" and makes identification of trends or tendencies difficult.

Based on assistance from the Treasury Board Secretariat in the assessment of the Tribunal's compliance with the Management Accountability Framework (MAF) in 2007-2008, the Tribunal put considerable effort in 2008-2009 into updating the Tribunal's risk profile and better aligning the language and indicators between the Report on Plans and Priorities and Departmental Performance Report. It also conducted a review of its information practices, to ensure compliance with the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act.

Other indicators of progress

The Status of the Artist Act is a specialized piece of legislation, of quite limited application to a very specific and narrow area of economic activity. As a result, indicators of effectiveness are frequently difficult to assess because of the problem of small numbers. The Tribunal uses certain indicators over multi-year periods to monitor the achievement of constructive professional relations in the cultural sector.

One such indicator is the proportion of complaints that are resolved without the necessity of a hearing by the Tribunal. Joint resolution of issues fosters cooperation between artists and producers, and saves time and money for the parties and the Tribunal by reducing the need for costly hearings. Accordingly, the Tribunal encourages parties to resolve as many issues as possible jointly before proceeding to a hearing, and the parties frequently find that they can resolve all the issues jointly. The Tribunal Secretariat provides assistance, where appropriate, through investigation and mediation, and in 2008-2009 emphasized augmenting staff's knowledge and skills in the issues facing the arts sector, so that the staff members are better able to meet the needs of stakeholders.

The table below shows the progress against this indicator. It should be noted that, as with many performance indicators, this is an approximate measure. Parties will withdraw complaints for various reasons. For example, sometimes the filing of a complaint will in itself bring the parties together to resolve the issue without any intervention of the Tribunal.

The negotiation of scale agreements is another indicator of constructive professional relations. Again, this is an approximate measure. The Tribunal can facilitate negotiations by granting certification, providing information about the Act's provisions for negotiations, and dealing with complaints of failure to bargain in good faith. It has little influence, however, over whether the parties actually pursue negotiations after certification, or over the results of such negotiations, unless one of the parties brings the matter before the Tribunal. Moreover, because there is no provision for first contract arbitration in the legislation, parties may be involved in bargaining for years without ever concluding an agreement.

With respect to the negotiation of scale agreements, a lot has been accomplished, if less than hoped for, as shown in the table below. Thirteen of the 24 certified artists' associations (54%) have negotiated a scale agreement under the Act, compared to the expected target of 19 (80%). (Note that this indicator has been adjusted from what was used in previous years, where we looked at first agreements signed within 5 years of certification. That indicator, on review over time, was found not to be representative.)

| Indicator | Target | Results since SAA was passed |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of complaints resolved without a hearing | At least 50% of all complaints are resolved without a hearing. | 50% were resolved without a hearing. |

| Proportion of certified artists' associations that have concluded scale agreements under the Act. | A minimum of 80% of certified artists' associations have concluded at least one new scale agreement under the Act. | 54% have negotiated at least one scale agreement. |

At the end of fiscal year 2008-2009, 18 certified artists' associations (75%) had at least one outstanding notice to bargain a new scale agreement.

Various amendments recommended in the 2002 evaluation of the Act5, such as requiring arbitration in specific situations for the settlement of first agreements, would facilitate the goal of successful negotiations following certification.

Section III – Supplementary Information

3.1 Financial Highlights

| ($ thousands) | Actual Spending 2008-09 | Alignment to Government of Canada Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budgetary | Non-Budgetary | Total | ||

| Processing of cases | 706 | 706 | Vibrant Canadian culture and heritage | |

| Corporate services | 309 | 309 | Vibrant Canadian culture and heritage | |

In encouraging constructive labour relations between self-employed artists and producers in its jurisdiction, the Tribunal expects that artists' income and working conditions will improve, artists will be more likely to pursue their careers in the arts, and producers will have an adequate pool of talented and trained artists. Thus, the Tribunal's strategic objective aligns with the Government's intended outcome of a vibrant Canadian culture and heritage.

| Program Activity |

Actual 2006-07 |

Actual 2007-08 |

2008-09 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Estimates |

Planned Revenue |

Total Authorities |

Actual | |||

| Processing of Cases | 1,341 | 1,055 | 1,973 | 1,973 | 2,061 | 1,015 |

| Total | 1,341 | 1,055 | 1,973 | 1,973 | 2,061 | 1,015 |

| Less: Non-respendable revenue | ||||||

| Plus: Cost of services received without charge | 405 | 422 | 491 | 491 | ||

| Total Tribunal Spending | 1,746 | 1,477 | 1,973 | 2,464 | 2,061 | 1,506 |

| Full-time Equivalents | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7 | ||

3.2 Other Items of Interest

Contact for Further Information

Canadian Artists and Producers Professional Relations Tribunal240 Sparks Street, 1st Floor West

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 1A1

Telephone: (613) 996-4052 or 1-800-263-2787

Fax: (613) 947-4125

E-mail: info@capprt-tcrpap.gc.ca

Web site: www.capprt-tcrpap.gc.ca

- Conference Board of Canada, Valuing Culture: Measuring and Understanding Canada's Creative Economy (2008)

- Hill Strategies Research, A Statistical Profile of Artists in Canada (2009)

- Available on the CAPPRT website

- The target of 60 days was developed for written final decisions. As noted in the next line of the table, the Tribunal did not render any final decisions in 2008-2009; this summary refers to interim decisions, issued by letter to the parties involved.

- The Report on the Statutory Review of the Status of the Artist Act is available on the Tribunal's website.